For Bianca Felicori Architecture is life. A collective experience that unfolds between familiar and unknown places.

You might see her running through the streets of Milano’s Corvetto neighborhood on her way to DOPO?—a project space she recently co-founded—, or sitting silently in the brutalist church of San Giovanni Bono, absorbed in her morning thoughts. Based between Milan and Brussels, Bianca Felicori is an Italian architect, researcher, and journalist who isn’t afraid to question the status quo. According to her, life and architecture are made of the same stuff; people, encounters, and connections, rather than bricks and mortar—a belief that led her to the creation of the digital archive, Forgotten Architecture.

It all started with a love of magazines and a profound interest in Architettura Radicale, an experimental architecture movement active in Italy between 1960 and 1975. Bianca graduated in History of Architecture at Politecnico di Milano with a thesis entitled “Arte, architettura e vita” (Art, Architecture and Life) on the relationship between art, architecture, and life in art historian Germano Celant’s written contributions to Casabella in the 60s. Currently, she is conducting a PhD at the University of Louvain (UCL). Her doctoral work is a continuation of her thesis and considers the same theme through three case studies: Hans Hollein in Vienna, the Archigram in London, and Superstudio in Italy. “What strikes me about the life of these architects is that, before undertaking their studies and careers, they painted. Many of them used to design utopias because they didn’t have commissions. Life was at the center. And this is what happened to me, too. I didn’t know how to reach my goals, but I knew that I wanted to put life at the center of my work, even if I am not able to define it right now.”

But Bianca’s interest in the Architettura Radicale movement was also fuelled by the lack of documentation and critique of architecture from the 60s. “We tend to focus only on a few major projects, and to forget everything that happened on the sidelines.”

It was in 2016, while working in the Domus archive to select magazine covers for an exhibition, that she began to question the sort of criteria that are traditionally employed for writing about history and architecture history specifically, “I wondered how many architects and movements had been left out of my education. At some point in history class, I had the chance to do a case study of architect Marcello D’Olivo, who I had never heard about before. He was an extraordinary figure, operating in the architectural and urban planning field, and was defined by Bruno Zevi as an organic architect. A friend of my father had worked with him and offered me all of his books, which are currently out of print, along with a series of articles. Then, while I was working in Udine [in the North East of Italy] I found out that many places from my childhood, for example, Zipser in Grado, where I used to play video games, were connected to Marcello D’Olivo.”

“Many of these architects used to design utopias because they didn’t have commissions. Life was at the center.”

A few years later, Bianca’s discovery of Casa Arnaldo Pomodoro, designed in 1968 by Ettore Sottsass Jr., further influenced Bianca’s journey. In May 2019, Bianca posted an article about Pomodoro’s apartment from an old issue of Domus and received innumerable comments from users claiming they recognized the space. Eventually, a private message appeared in Bianca’s Inbox: she was invited to have coffee by the owner of the house. What she discovered, upon visiting the apartment, was an uncharted, perfectly preserved universe. A universe that was missing from the history books. Astonished, she began researching drawings and other materials related to the apartment’s origin together with the Sottsass Archive.

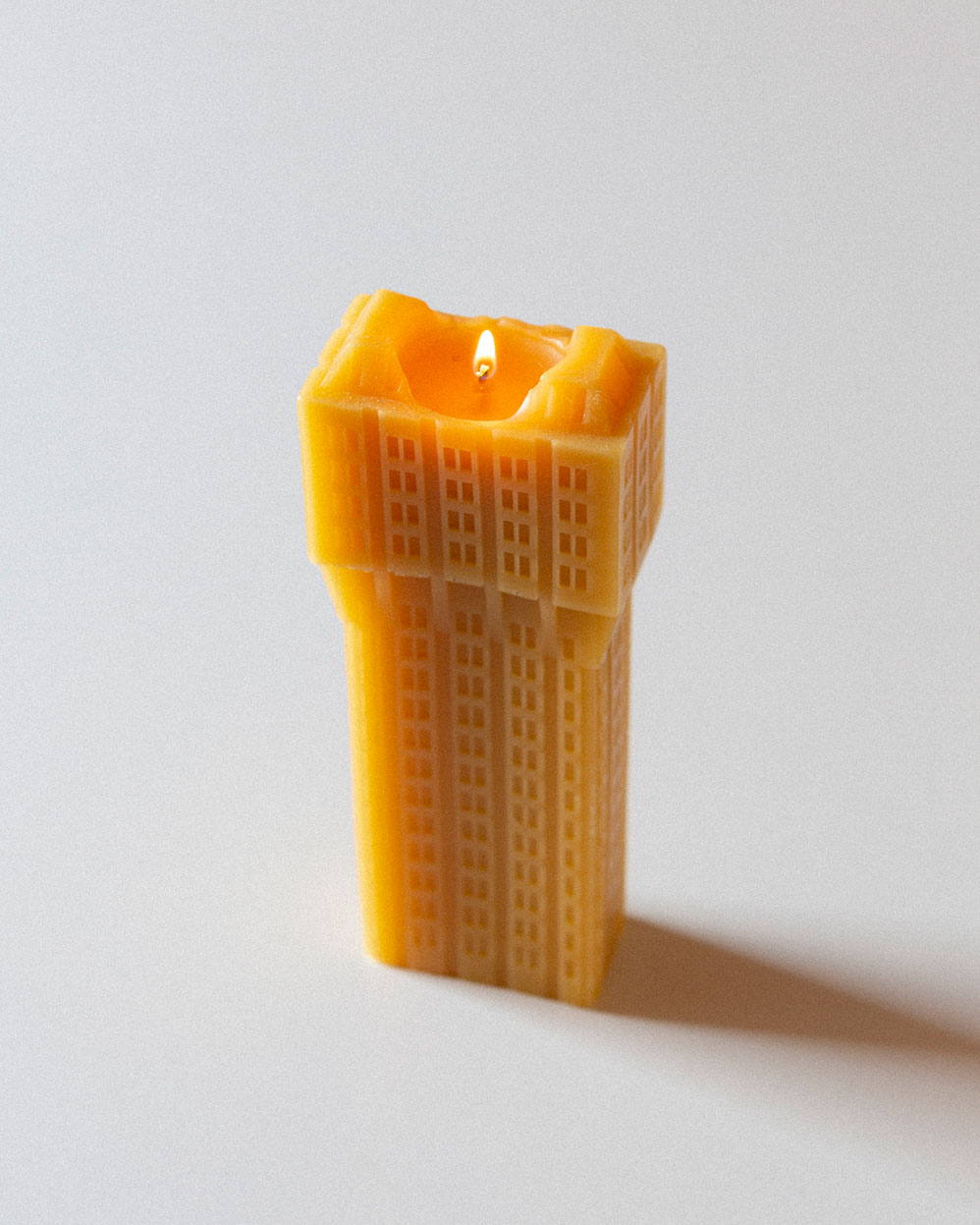

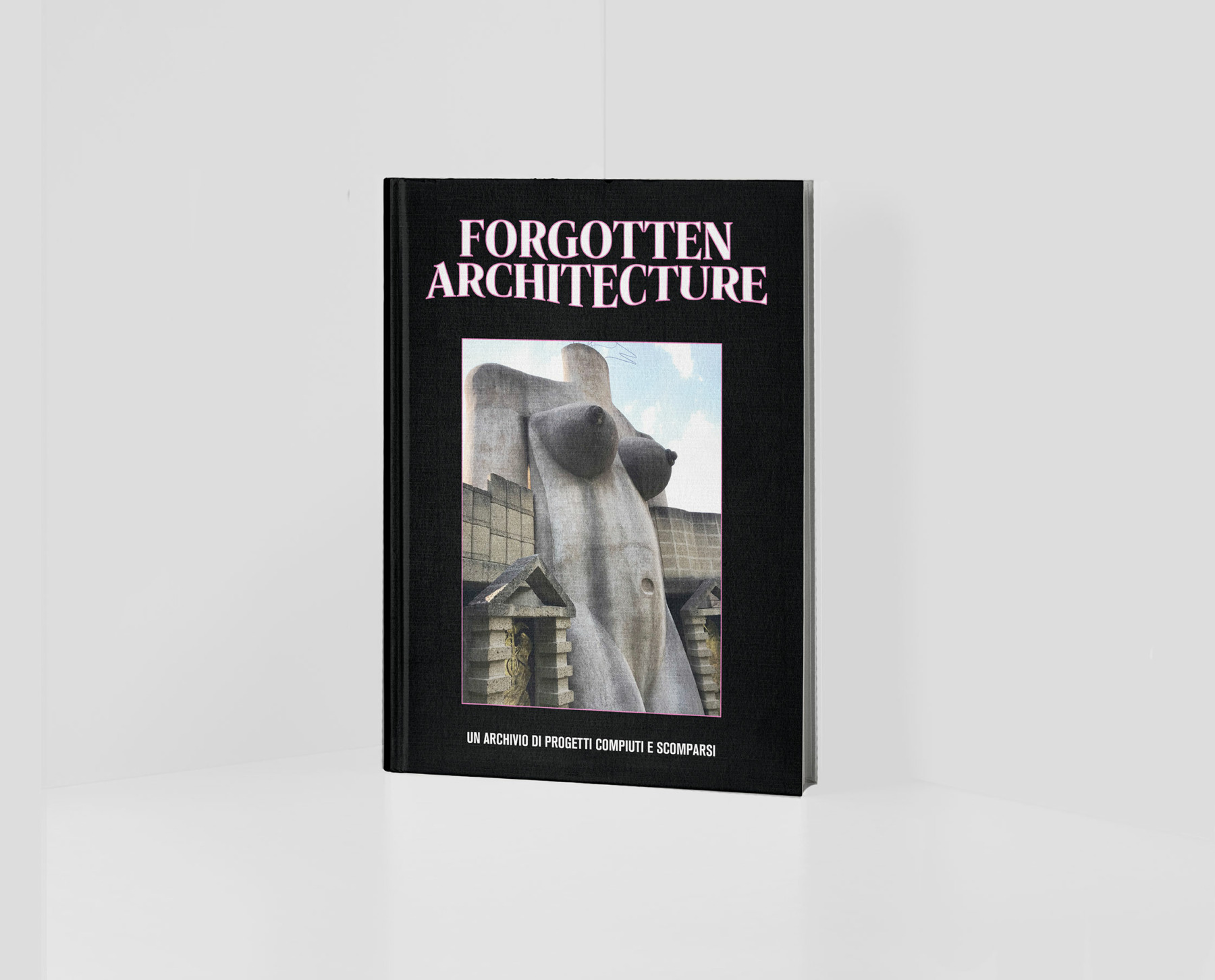

The episode also perfectly summarizes the nature of Forgotten Architecture, which was launched on Facebook shortly thereafter, and later turned into an Instagram account and a book published by Prima o Mai.

While working at the Cuba Pavilion at the 22nd International Exhibition at Triennale Milano, Bianca made another discovery: the Escula de Musica designed by Vittorio Garatti. This time she decided to create a Facebook page and share the building with her contacts. ‘’Forgotten Architecture started this way, I posted what I was finding during my research in magazines, books, monographic catalogs, and so on, then other people did the same. There are so many things I haven’t seen yet—a thought that was actually shared by many other students and professionals who spontaneously joined the community and started posting their own architectural encounters”.

The difference between Bianca’s project and a traditional archive is precisely how it’s produced: Forgotten Architecture is a digital catalog that grows with public and collective contributions. Even though the typical content shared by the community is niche architecture, the archive actually attracts an ever-wider audience. “I believe that one of the reasons why Forgotten Architecture has been so successful is that it is Pop, it approaches an elitist discipline with a casual spirit. We need to change the language of architecture to avoid a generational gap. I opened my Instagram account when I was 15, it is part of me. There are a lot of researchers that broke out of the academic box and became cool people, some of them even became influencers. This phenomenon is interesting. My goal is to do the same with the archives,” says Bianca. Indeed, many archives are incredible places full of treasurers, but in the collective imagination they are still often seen as “bookworm” houses.

‘’Forgotten Architecture started this way, I posted what I was finding during my research in magazines, books, monographic catalogs, and so on, then other people did the same.”

Collaborative work is a true expression of Bianca’s generation: it is a key feature of Forgotten Architecture, and a defining quality of DOPO?, Bianca’s latest endeavour. Co-founded alongside other architects, DOPO? explores the potential of shared working environments and their relationship with cultural production. It functions both as a co-working space and a venue for local book presentations and exhibitions. “What we are doing here is using our disciplines to envision a future life,” says Bianca. In this sense, DOPO?’s aspirations, perfectly embody the goal of the 60s and 70s movements mentioned earlier: finding ever-new ways of being an architect.

When she is not traveling around the globe, Bianca enters DOPO? at 9:30 in the morning. But her day usually begins much earlier—running, biking, and training, all while searching for hidden and unusual buildings or visiting the ones she loves the most. “When I need to be alone, I run to the San Giovanni Bono church, I enter and sit, sometimes I cry, then I go home and start my day. I make a lot of decisions—personal and professional ones—when I run in the morning. It is all part of the same process.” Even when Bianca is by herself, life, and architecture continuously overlap, becoming research, discovery, and exchange. Perhaps this is also the secret to appreciating what others, before her, have overlooked or forgotten.

Bianca Felicori is an Italian researcher and architect based between Milan and Brussels. She is the founder of Forgotten Architecture, a collaborative platform that collects forgotten and lesser-known modern architecture worldwide. Together with a group of architects, she also recently founded DOPO? a space for cultural work, in Milano’s Corvetto neighborhood.

Text: Giulia Bortoluzzi

Photography: Mattia Greghi