In the Indian district of Gaya, in Bihar, stands the tree under which the Buddha received enlightenment. Its roots are ancient but every season new leaves appear on the tree’s branches and new generations gather under it, seeking the legend of the Buddha.

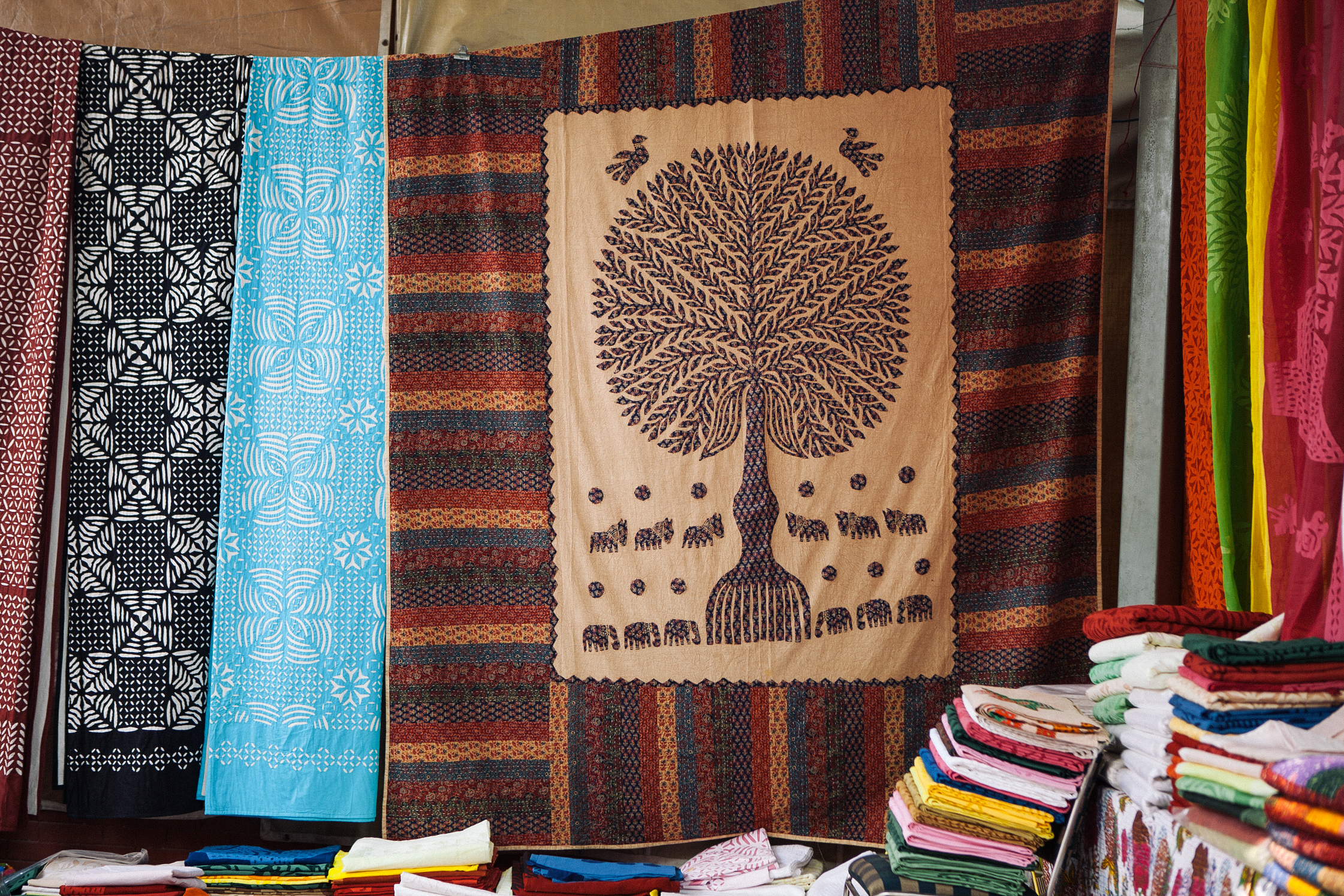

For some of those born in Gaya, like a young woman named Usha Prajapati, the Bodhi tree is a metaphor for life and work. Usha’s design collective for women, Samoolam (the Sanskrit word for collective roots), is based on this idea of constant regeneration and expansion, whilst forging an ever-stronger connection with its roots. The collective is based in her father’s garage in Gaya, but as more women join the group in Bihar, and now in New Delhi, Samoolam is spreading its branches.

In collaboration with Germany’s BMZ, we explore the developing world through the eyes of interesting individuals and focus on their noteworthy initiatives.

More than 1000 kilometres away from her roots in Gaya, Usha wakes up to the light streaming through her cozy apartment in New Delhi, at 6AM every morning. She’d laugh if you called her a workaholic, but there’s rarely a moment in the 32-year-old’s day, when she is not busy. Whether directed at work or household chores, her total absorption and laser sharp focus is the result of a lifetime of yoga. Usha, the youngest of seven siblings, has come to love living by herself – a somewhat difficult choice for young women in Delhi. On her fridge, you will find a magnet with the following words by Ashley Rice:

“There are women who make things better, simply by showing up. There are women who make things happen. There are women who make their way. There are women who make a difference. And women who make us smile. There are women of wit and wisdom who through strength and courage make it through. There are women who change the world everyday, women like you.”

Samoolam, Usha’s design collective, which is making a name for its beautiful hand-crocheted lifestyle products, is incredible not just because its founder is young, talented and inspiring, but because its process of creation is held together by a network of strong and talented women much like her – women who make things happen, who are changing their worlds, one crochet bead at a time.

Like most women who were born to change the world, Usha is stubborn. She always has been. Not in the petulant, demanding manner of a young child, but resilient, like the old tree back home. When she first left the tiny district of Gaya at 19, to join the cosmopolitan and highly reputed National Institute of Design at Ahmedabad, she was terrified, almost paralyzed at the culture shock.

“When I got to the campus for my interview and saw the girls decked out in these crazy costumes – high heels, transparent shirts, big eye make-up and red lips like nothing I had seen on the television or the magazines – I was standing there in a salwar kameez with oiled hair. I looked around me and thought: This is a crazy place. I’ll never belong here.”

Neither her lack of fashion sense nor her inability to speak English though, could keep Usha from the world of design. The interview panel at NID was stunned at her unselfconscious honesty and confidence about growing up in a village – with a house full of siblings, a father who was a garage mechanic and a mother who milked cows and harvested grain – Usha was cut from a different cloth. Her parents were illiterate, but all of Usha’s siblings had left Gaya for higher education. Her composure was incredible. When one jury member tried to rattle her by ridiculing her poor English, she said “We’re in India, aren’t we? It isn’t my problem that I don’t speak English, it’s yours that you don’t understand my language.”

Usha had the talent to back up this steely-eyed confidence too. Growing up in a home with so many siblings had its advantages. Each one had their own talents – cooking, sewing, painting, singing, dancing – and teachers were only too happy to stop by for lessons; seven children was practically an entire classroom. Inspiration and competition were never too hard to come by either. By the time Usha was 13, she had won nearly Rs 6000 by sending her paintings to local magazines and art fairs. Everyone in the family believed performing arts were a source of spiritual purification, and encouraged each other to be the best at what they chose.

Even so, like many parts of India, Gaya was a caste-conscious and gender-biased society. When Usha’s eldest sister decided to move out to study architecture, the village ex-communicated their family. As each successive sister left, matters became worse: The sisters would be corrupted by the city, village elders warned them, they would never find a husband. It was only by the time Usha left for NID – and her elder sisters had settled in cities, found jobs, and started to send money home – that Gaya began to accept the value of educating daughters. Usha’s parents were welcomed to weddings and village functions once more.

In contrast, Usha’s own life – once raucous, full of shared secrets and laughter in Gaya – had turned deathly silent at NID. Surrounded by English speakers, whose social rituals (like dating), music (Enigma, Bob Dylan), and jokes were totally alien to her, Usha felt a misfit both in class and outside of it. At home, she was the universally adored youngest sibling, recipient of affection and hand-me-down gifts. In Ahmedabad, she was thrown into independence, and worse, into loneliness.

“It would take at least a week for a letter from home to reach me, every time. I was overwhelmed and completely depressed. I wanted to run away. That first year was my personal hell,” she recalls.

However, she was not unaccustomed to hardship. Her family had endured much in Gaya: Her father had run away from his own home to become a garage apprentice at 11. He was so fiercely independent that even after he fell in love, he refused to marry until he’d built a garage and home of his own. Usha says her mother had hoped to bear him sons so they could help him run the garage, but after the first boy, she had only daughters.

“He was a strict man in some ways, but with a very big heart. We never cuddled our father or played around with him. He was always busy, very serious. He worked on large vehicles at night, and smaller ones through the day. Often, days would go by before we got to see him.”

Distracting herself from the lack of a social life by turning her attention to work, Usha managed superb grades in her first year. When she presented her portfolio in front of a jury – empanelled faculty as well as over a hundred students – at the end of the year, her confidence finally cracked. The inability to explain her artistic process, all because she could not speak English, had finally become too much to bear. The faculty, convinced of Usha’s talent, immediately hired a professor of English to come by the campus and tutor her every day.

At Samoolam, Usha is determined that women should imbibe not just crochet-skills, but life skills, including English, in the course of their work. Women who have been with Samoolam for a few years are groomed to take up leadership roles, teach other women, deal with vendors, and learn basic computer skills so they can communicate with Usha wherever she is. Sitting in that tiny 4×4 classroom with her English tutor, Usha says she learned what English was really about: building confidence. Her only instruction was to never break eye-contact with her teacher no matter how much she stammered or how ungrammatical she felt her sentences were.

“Once I learned to be fluent, even if not necessarily brilliant at English, I knew nothing could hold me back. I literally woke up one morning in the hostel thinking: This is it. I’m the best in every way now.”

Usha credits her father for her solid work ethic and inner strength, but also for her instinct to give back to the community. On the rare morning when he found himself free, he would sit in the yard in front of the house with a large thermos of tea, offering chai to passersby on their way to work or school. “Even when times were hard, we were always taught to cook extra food, so that we could feed anyone who stopped by for a warm meal. People in the village knew that, and respected him for it,” she says. Her love for design, but more importantly, for entrepreneurship, has taken Usha to USA, Sri Lanka, China, and all over the world on fellowships and grants. But no matter how far she flies, Usha Prajapati is never too far from her roots.

Usha, thank you for sharing your story with us. Find more information on Usha’s non-profit organization, Samoolam.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who present a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

This is our second time in India – previously, we visited master printmaker Vijendra Chhipa in Bagru.

Photography: Andrew Kaineder

Text: Nishita Jha