In the heart of Istanbul’s never ending chaos of car honks, muezzin calls and crying seagulls Can and Aslı have built their own little creative island. Having moved from London to Istanbul just one year ago, Aslı is running the graphic design studio Future Anecdotes Istanbul in Galata whereas Can belongs to the generation of young conceptual artist from Turkey that appeared on the international art-radar within the last years. Originally trained as an architect the city of Istanbul serves as his greatest muse and you won’t meet somebody else talking so passionately about the anomalies and peculiarities of a city.

The third family member petit-beurre a Persian cat just found his divine purpose during the shooting performing in front of our camera.

Where are you two from and what are you doing?

Can: I am an artist and I am also teaching at the university here.

I am originally from Ankara but started showing my work in Istanbul around 1998. I was already very much involved with the art scene here for quite a long while but I was still living in Ankara. I left Ankara and moved to London, because Aslı was living there at the time. I came back to Turkey in 2008 and moved straight to Istanbul.

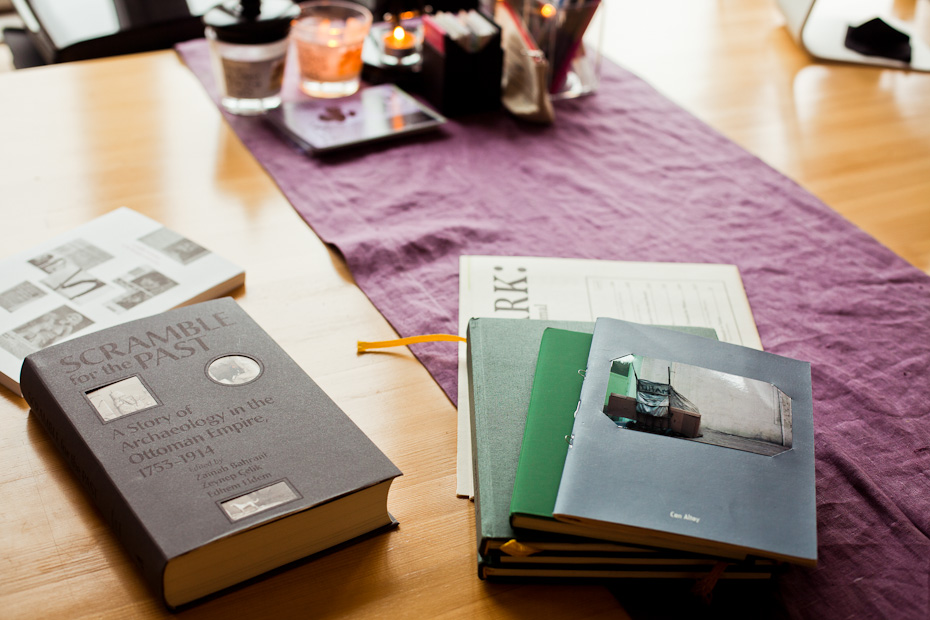

Aslı: I was doing my Masters at Chelsea College of Art and after five years in London I moved to Istanbul last year. I am a graphic designer and after I finished my studies I set up a studio with a partner in London, now the studio is functioning from Istanbul where I mainly work on printed matter and identity. One of the recent projects I did in London was a book project for Book Works. In Istanbul we just finished a project called “Scramble for the Past” it included a book and exhibition graphics for one of the opening exhibitions of the new institution SALT Galata.

Can: Aslı also designed a few of my books. We collaborate a lot, not only as artist and designer but also doing projects together.

When you came back from London it was totally evident that you go to Istanbul and not back to Ankara?

Aslı: No, Ankara wasn’t really in the equation after living in London for five years. But I guess we are not totally settled yet. I am happy here but I could also imagine a different place.

Can: I am very much here, actually (both laugh).

What’s the main difference between Ankara and Istanbul?

Aslı: Well, as some capital cities Ankara is suffering from the heavy bureaucratic aura. It’s very formal and quiet so it doesn’t allow arbitrariness. But the people from Ankara, they are really great. You can find all different kinds of subcultures. The youth is quite self-initiated, enthusiastic about collaborating and getting together, so small gatherings play a big role in social life. Since the city doesn’t offer much you have to entertain yourself.

Can: Of course Ankara has a great influence on my work. I emerged as an artist by mainly doing work in Ankara and about Ankara. In that sense it is very definitive in the development of myself. I have a very close bond to it. I tried to resist the centralizing forces of Istanbul for a certain time, because everyone of my generation went to Istanbul and it has this giant pull. But after a certain point my resistance didn’t make sense anymore because there was no reason left for me to stay in Ankara. Istanbul is much wider in terms of the possibilities it contains.

Also the texture of the city Istanbul is very different than Ankara. Ankara is composed of zones, every place has its own peculiar kind of feeling and establishment whereas Istanbul is much more mixed up and this is very interesting to live and pass through. I am quite happy to be here.

If you had to describe Istanbul in a few sentence, what are the essentials of Istanbul?

Can: East meets west (laughs). What touches me most about Istanbul are the constantly changing view-points. This can be literally when you walk through the streets and suddenly you see the sea but it can also mean you are walking on one street and suddenly you are in a totally different world. The fact that you encounter so many dark corners and so many harsh contrasts by just walking through the city for me is the most essential thing about Istanbul.

Aslı: I never lived in Istanbul before so I am still constantly surprised. It has this Benjamin Button syndrome. A very old city that gets younger every day and you can never predict what is happening next.

Can, you are coming from architecture but you have been solely working as an artist. Was that a conscious decision or more like a natural development?

Can: It was partly conscious. I graduated and worked a little bit but somehow I always wanted to be able to say something, to communicate ideas and be able to express critique. So I was very much in between, thinking whether I should go into complete theory, into writing. But I also always liked to create things, setting up spaces and being able to do things. I was also very much concerned about the problems of architecture and the limitations of architecture in particular. I liked dealing with urban ideas in a social, economical and political construct and as far as I saw it, all this wasn’t possible if you work as a practicing architect. There is also a personal drive which is not only rational, to do something wild, or I don’t know, poetical maybe, something that doesn’t surrender to explanation right away.

In the beginning I didn’t know much about contemporary art but there were two things that really turned my way of thinking around. The first thing was the Istanbul Biennale in 1997 curated by Rosa Martinez. I was also attending the graduate school, reading a lot and attending seminars on philosophy and contemporary art, so that shaped my practice a lot and I started doing things, producing and proposing to show them. Luckily, I got noticed quite quickly and I was able to show my work internationally to a great extend.

What was the first big project you did?

Can: The first project that got noticed was the Minibar Project. It was about Ankara, about the city’s nightlife drinking culture and how the city space was appropriated by young people bringing their own drinks, making their own cocktails without having a bar. This whole scene emerged and was called Minibar. I documented this emergence and reflected on it, there were interviews with people and all kinds of material gathered to make an installation about the situation.

The Papermen piece (“We’re Papermen”, he said), my second long-term work, had a lot do with Istanbul. It was about the unofficial garbage collection in big cities but with a strong focus on Istanbul and Ankara. It’s about how the papermen navigate the city, how they find and extract the things to recycle and how this is actually related to the larger system of how the city works. The papermen are really organized, even if we call it an informal system it does not mean that it is not organized. It is maybe even more articulate than the official garbage collection system.

Are you more interested in the constitution of informal systems or in the way they are integrated into the big system of the city?

Can: I think I am more interested in the idea of how we inhabit the system in a way that it challenges the system. For me this is an existential question. Whether we can inhabit a system by pushing its boundaries or by challenging it and not only submitting ourselves. For me the most interesting thing about the Papermen Project was exactly this.

Do you have a top five of informal systems of Istanbul?

Can:(laughs)

Aslı: I think the street cats and how the neighborhoods are caring for them is a very nice example.

Can: Yes, definitely. All the stray animals and how they adapt and live in the city. There is this historical rupture about the street dogs in the city. In the 19th century when the Ottoman Empire wanted to turn Istanbul into a modern city, they collected thousands of dogs from the streets and send them to some islands. There was this very traumatic story about how the neighborhood reacted to it and now still there is this really strong bond between the people and the street animals. You acknowledge them and put water and food for them on the street. It is definitely a co-habitation.

On a totally different note, I have also been very interested in the stuffed mussels they sell as street food in Istanbul. I was looking at how they are fished because most of them come from the Bosphorus, and how they are produced and distributed in the city. This also touches on urban realities and there are all kinds of precarious stories related to it.

But I think my number one are still the papermen.

Though what might be important to say is that I am not completely celebrating them because there are always very harsh stories related to these situations too.

What are informal systems adding to the city?

Can: I think mostly the informal sector is an intervention but also a contribution. It is not necessarily good or bad but it definitely affects the way the city works and adds something to it. But of course we can’t include all informal systems because then we have to talk about the Mafia as well.

Do you have a picture about the ideal public space?

Can: The ideal public space does not exist but I am following the idea that the ideal public space is a space for common production and common critique but also for confrontation. It is a place of encounter where people can meet face to face. I think that all encounters are transformative; every encounter changes us.

I have one more question that interests me very much. Why are parks not working in Istanbul?

Can: There are two replies to this in my opinion. One is the fact that a park is probably one of the most regulated public spaces. It relates very much to the Late Ottoman and Republican modernizations of the Turkish cities. Parks were a model that was brought from Europe. You could say it is an imported urban space of artificial nature.

The second reply I think is more important. In Istanbul, public space is male space. The gender issue is something that we either avoid to face or we just agree to leave it like that.

Aslı: Yes I think this explains the whole problem. Even we have a park close by I hesitate going there because there is that atmosphere almost like if you go there alone as a woman, the message is you don’t actually want to be alone.

Can: You can observe it also in the more traditional neighborhoods. You have the coffee houses where all the man gather and the women will either be chatting from window to window inside the house or gathering at the doorstep of the house.

What is your favorite place in the city?

Can and Aslı: upstairs, our terrace!

Can: I like Yildiz Park very much but I don’t think we have a place where we really go a lot. We are still looking for it, or it changes all the time.

Aslı: I really like the reading room at the new SALT building. I think this is our favorite new place.

It was a really nice afternoon with you two, thank you for the interview!

If you want to have a look at Aslı’s recent Book Projects, take a look here.

Photos: Ege Okal

Interview & Text: Antonia Märzhäuser