On the outskirts of Paris, Jeremy comes to find us at the entrance of his building with his lunch in a bag. Regardless of his perhaps resilient absolute emergence, as soon as getting a short glimpse of Jeremy’s pale blue eyes, one cannot dismiss the fragility hiding in them. Yes, a delicate substance like glass immediately comes to mind as a suitable comparison for the Parisian glassblower. Moments later, Jeremy’s judged fragility is nothing less than a permanent mark of life’s reality and is there to be both respected and admired.

We talk about the encounter with glass and his apprenticeship; a learning by doing method. When discussing his urge to make things change for the glass industry in France, he looks you right in the eyes and transmits the genuine concern and need manifested within his self. One acknowledges his speech as observant and sharp, made to measure the media format. But as you succeed taking him into a dialogue, it remains complicated to separate the man from the glassblower, both being so intricate. Find out what made Jeremy Maxwell Wintrebert the person he is now, making him really one of the exceptions in his profession and our seemingly familiarized generation.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on their site.

A very straight forward question for the start, who are you and what is your story?

I was born in Paris and raised in Africa for 13 years. My family and I have lived in different African countries; Ivory Coast, Gabon and Cameroon. Because my father was into the fruit industry, we often lived between the cities and plantations. My mother was American and my dad French. Both were collectors, passionate about craftsmanship. Thanks to their passion I grew up in a creative environment. In every city we set camp, they used to bring us to local markets to meet craftsmen. As a kid I sometimes worked on markets for ceramists.

Between the age of 13 and 14, I lost my two parents, one after the other. My aunt, who was in Paris, adopted me. I came back to France and continued school. I was in a Parisian high school with young people who dressed up and acted according to social codes and a hierarchy, unlike anything I had known. Plus, they had shoes on, I grew up barefoot. At 18, I graduated which freed me from this education I disagreed with. Then I left for the U.S to explore the country, I first stopped in Seattle. I was living out of several small jobs including one at the Seattle airport! I stayed there a year in between round trips to California.

When did you discover glass as a material?

One day while I wandered through the U.S, I walked in a glass studio, I saw hot glass there and what is called “a gather.” I simply fell in love. Ever since, glass became a guide in my life. Soon after I discovered glass, I had a car crash during which I went through the windscreen. I had serious injuries, which I had chance to come through. A long convalescence was needed and it forced me to stay in bed. This was a time of solitude. But while I was recovering, I became obsessed with glass. As soon as I could start walking again with a stick, I went directly to San Francisco, California, where many glassblowers have studios. I had no experience, I had only seen glass. On the way I met Jaime Guerrero, a Mexican American, who was setting up a studio in Alameda. I started to learn and work glass with him, then little by little I began working with other glassblowers.

So you learned by doing. Where did you continue your training?

After 2 years in San Francisco I was contacted by Jacksonville University, Florida to be offered a one year artist residency. This marked the beginning of my “Mama Africa” series. During that year in Jacksonville, I met numerous glassblowers who were using the university’s studio. Guys that I would later on go visit in their cities. After that I made a stop in Murano, Italy at Davide Salvadore’s studio. I had only met him once in California, so I had to play it smart and have some nerve. Only with my backpack I went every day to his studio asking for work and one day he said “yes”.

I stayed there a bit then went back to the States, where I got a job in Miami. A billionaire just discovered glassblowing and wanted to create his own workshop. He was seeing things big (and was a bit crazy too)! I designed the studio’s furniture and crazy pieces for him, like a glass staircase. After a year the experience was slowly getting to an end. I was looking for something else to bounce back. I googled “glass France” and found nothing! Besides traditional houses, like Baccarat or Lalique, there was nothing. I felt there was an opportunity in France, since everything has to be done. There was no specific market for free blowing, which is my specialty. Everything I do is free hand work, no tools, no molds. I only work with gravity forces, the strength of my assistants and an oven. I took the chance and went back to France, my home.

I unfortunately realized that reality was completely different. As there was no market, there were no facilities, no places to get tools or colors, no studios, no nothing. On top of it, I came with no budget. To get things started and put some money aside I did various jobs like barman, mover, delivery boy for a beer company, I built TV sets, whatever job was available I would take it. One year later, I heard of a studio called “La Compagnie des Verriers” was re-opening near Nancy, at Vannes-le-Châtel in the North-East of France. Straight away I went there. I met some people, who I now work with, like Antoine Brodin. From then on, I was able to produce again and managed to buy my colors in London and my tools in Murano.

What was your aim with the pieces you were producing then?

I soon realized that it was hard to work with art galleries. As there was no market, they didn’t even want to hear about me. For months, I contacted design shops, who also declined because my pieces were closer to sculpture than design. On a regular basis I contacted the boutique Maxalto, which was located on rue du Bac. One day, I showed them pieces with interesting shapes but with no colors. They let a “good idea” out, I took it as a “yes,” and made 7 pieces. Two weeks later, I brought them to the boutique. They loved it and put the pieces on display in the windows. That was a starting point. My work was shown on the rue du Bac (the street is renowned for its contemporary furniture and design shops), and everybody was wondering who is this guy blowing glass?

A woman has a very important part in my carreer, Marianne Guedin. She also works with glass and introduced me into the design world. All of a sudden, I was part of the 2009 “Talents à la Carte,” a selection of young designers at Maison&Objet (the Parisian decoration and design fair). As an artist part of this selection I was given a stand. For five days, I learned a lot on what buyers are looking for, the prices and how galleries operate. I was spotted by galleries from London and Amsterdam and also by Galerie Bensimon in Paris. Since then, they represent me and help on the communication and project development.

How would you define your approach? In between craftsman, designer, artist, it doesn’t seem not be easy for you in France, with people tending to put you in a box…

That is true, people cannot put me in a box, and I play a lot with that lever. Depending on both the type of public looking at my work or the kind of pieces I show, I can be a designer, an artist or a craftsman. In France you have to be either one or another. It’s unbelievable and I like it! For example my latest show at Galerie Bensimon was presented as design. This was actually only a veil, because the pieces are always unique and hand crafted. The shapes and the drawings are imagined with a designer’s approach, but the making is hand crafted. I blow the pieces and each are unique, like sculptures.

Based on that, how does your Parisian gallery present you?

As a glassblower. They adjust their speech depending on the type of person, being a journalist, a collector, or a visitor. It is interesting now with articles that have been written on my work, to compare how people describe me. 9 times out of 10, it is as glassblower, which I find super interesting. I started making video with Jerôme de Gerlache from that perspective; giving a realistic image of a glassblower today. I’m young, I’m short (laugh), I’m nomad and tattooed…

Do you feel a need for people to bring back hand work into their lives?

Absolutely, I feel and hear about this urge. I see people’s eyes sparkling when I talk about my work. People with 9 to 5 office hours just think “what a life.” Few days ago, I went to meet young people studying glass in a technical high school. 60 passionate youngsters aged from 15 to 18, it was a blast! I did a workshop with them; they are a small army of glassblower. I mean, they want to develop the trade in France and the only thing they want is to work!

Did you give them advice?

The no.1 problem for them, and they already know this, is that there is no work, unless they go abroad. I don’t want to see them flee; it is here that we have to build things. I have been very honest by telling them that the key is to be determined. You have to know how to provide for yourself, how to ask for money, and talk about your work. In the art and design world, coming with a story is an added value. Your life path is a tale, essentially a great story for the one who’ll invest in a piece. We have to focus on creating a market that we are going to make with great pieces and good work.

What is the aim of the speech and views that you are spreading?

I want to promote handwork in France. Here, theoretical and intellectual trainings are valued and working with your hands is considered as low on the social scale. It is a very interesting matter to work on. The different cultures I grew up in did value those who mastered handwork; I personally admire these individuals. To me, that way of considering things is unimaginable. Through my speech and actions I want to value the intelligence lying in handwork.

Some designers come to you to produce their glass pieces, how do you collaborate?

It is a very good question that keeps me thinking a lot. Before, I used to accept many offers because I was hungry. Now I will not work with someone who’s not interested in glass. I want to work with people who are open to learn about methods and appreciate it; then we’ll talk about the piece.

How would you like the situation to change?

My next big project is to set up a studio in France. A place dedicated to training, sharing and welcoming people from all background. Through the years, I built a solid team. That is something but I’d like to have like 12 assistants! Following the example of my experience, I believe that you actually learn by doing.

It is a physically demanding work. Do have you a special diet and preparation?

Yes indeed very demanding. I have a diet, I exercise and lift weights, and I do not drink or smoke. After a day at the studio, which took all my energy, I just go home and sleep. For full work weeks, a special physical and psychological prep is required because we produce such big pieces. When we leave for several days- working sessions we have an assistant who makes sure we are in good health, with an appropriate rhythm; just like athletes! At the same time you also have to develop creative ideas.

How do you protect your creativity?

I develop my creativity through spirituality. That is to say that creativity itself is not mine. I do meditation on regular basis, which allows me to let ideas and creativity go right through me.

What does your life as a nomad, always in between different studios, looks like?

That is funny; the high school students asked me “what do you do with your private life?” (laugh). I actually don’t have one. I’m a loner. All I need is Wi-Fi access (laughing again), my bag with few clothes, my toothbrush, and my tools always ready to go. In between work sessions and travels, I do a lot of PR, pictures, talk about my projects, I update my website…

When was your latest day off and what did you do?

I take some free time, mostly half days. I love climbing and biking. My last half-day was this week. I went golfing with friends and at 2pm I was back at work. The week before, I went climbing. And the month before was full-time work. Tomorrow, I’m going to Amsterdam for one week session, then Germany where I’m invited at a school for a workshop. Then I’ll take some time off to organize my house move.

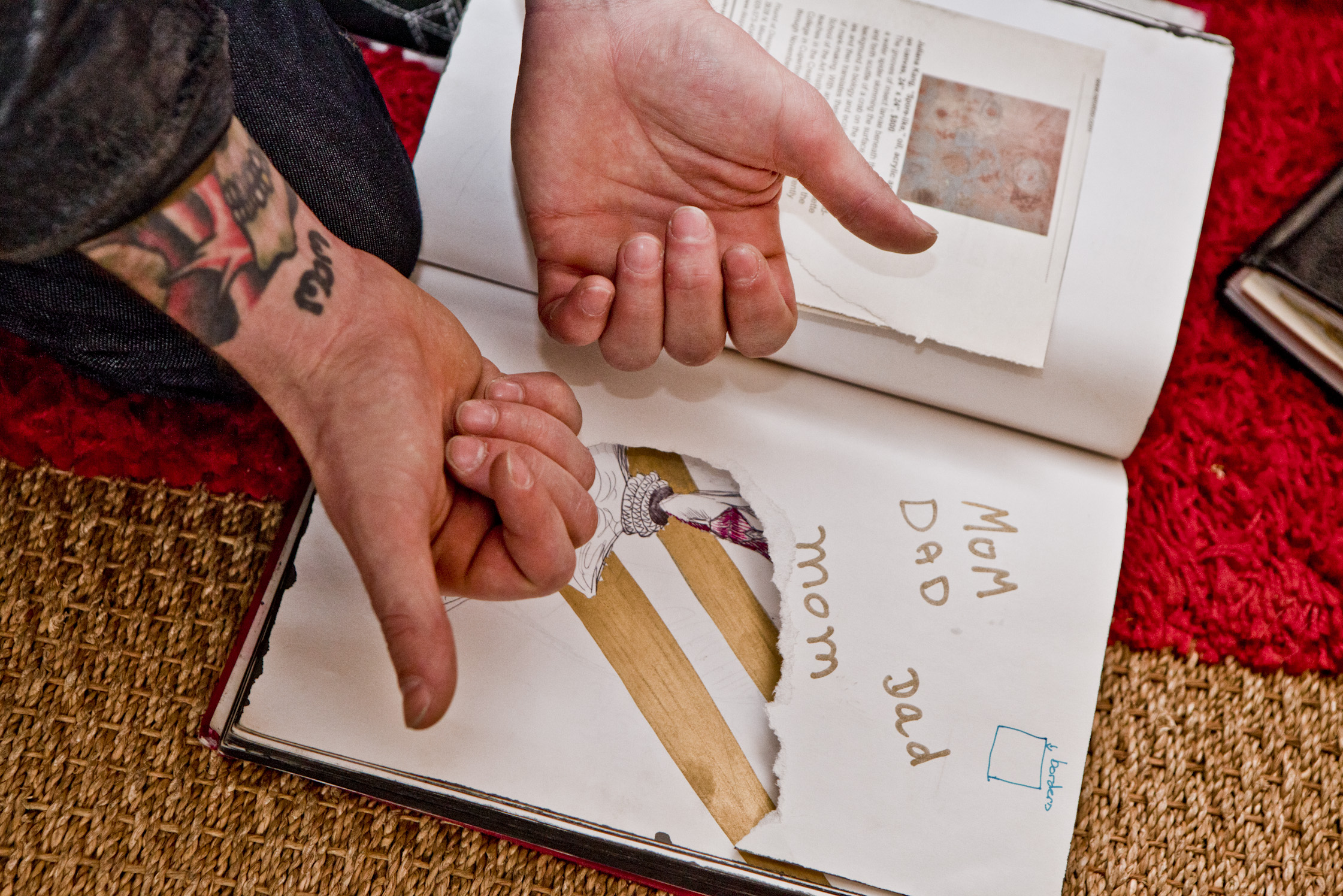

Can you tell us about your tattoos?

It is the story of my life. The left arm is about Africa and on the right arm I carry all the dearest persons that I lost. Here’s a memory of my ex-biker life. Here under there is Jesus “Le Costaud,” who represents the spiritual life of my youth. I was baptized at 18. The rest is only for me.

Do you have an idea for a next tattoo?

I think I’m tired of pain. Before, I had a higher tolerance of pain, but I think my stock is empty. After my accidents and tattoos, four months I just spent fighting against a nasty cancer, I want to be done with pain. My body is scarred. When my dog died, I decided that it was over and my last tattoo would be for him. I was always joking about putting him on my back. I did it and I knew it was the last one.

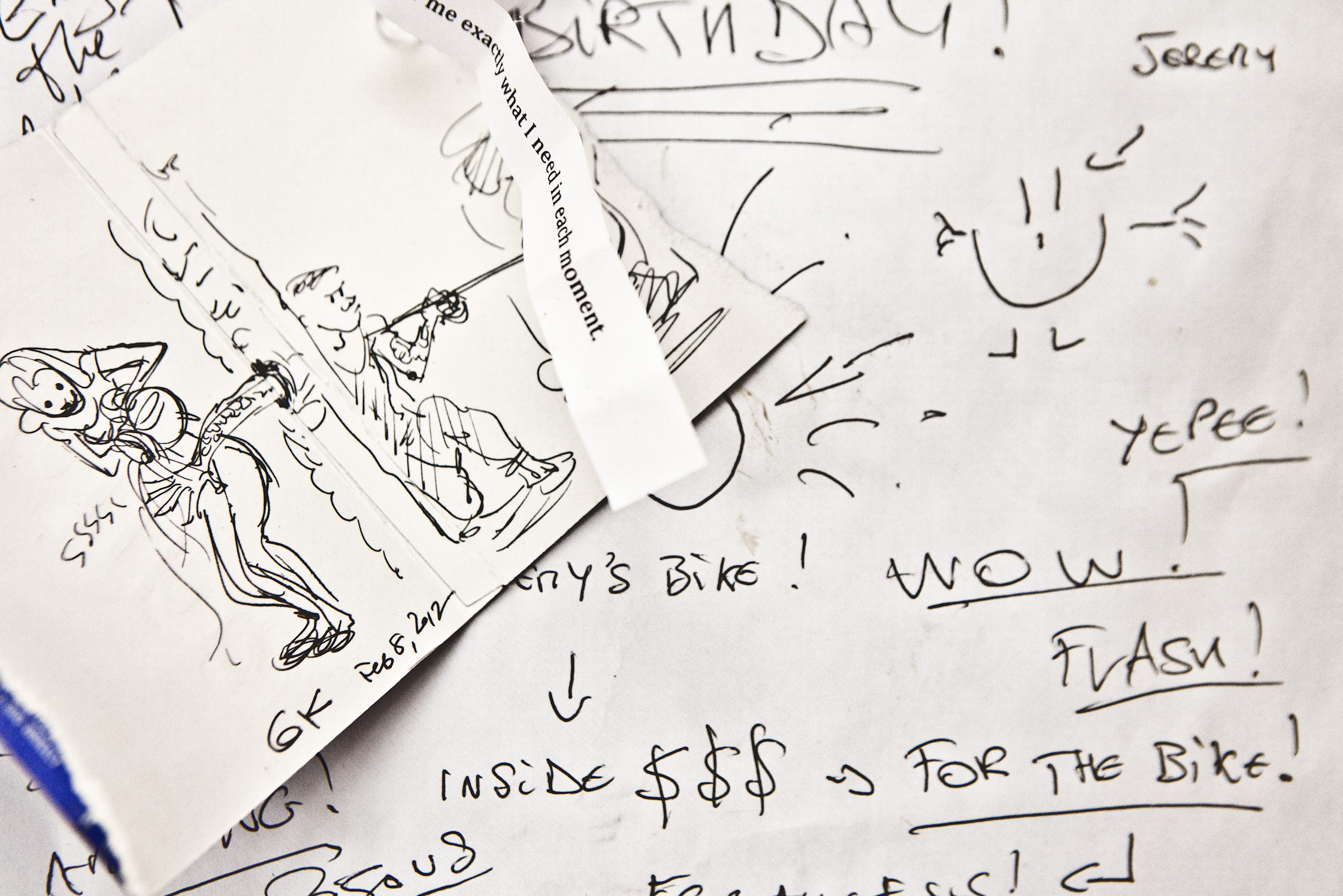

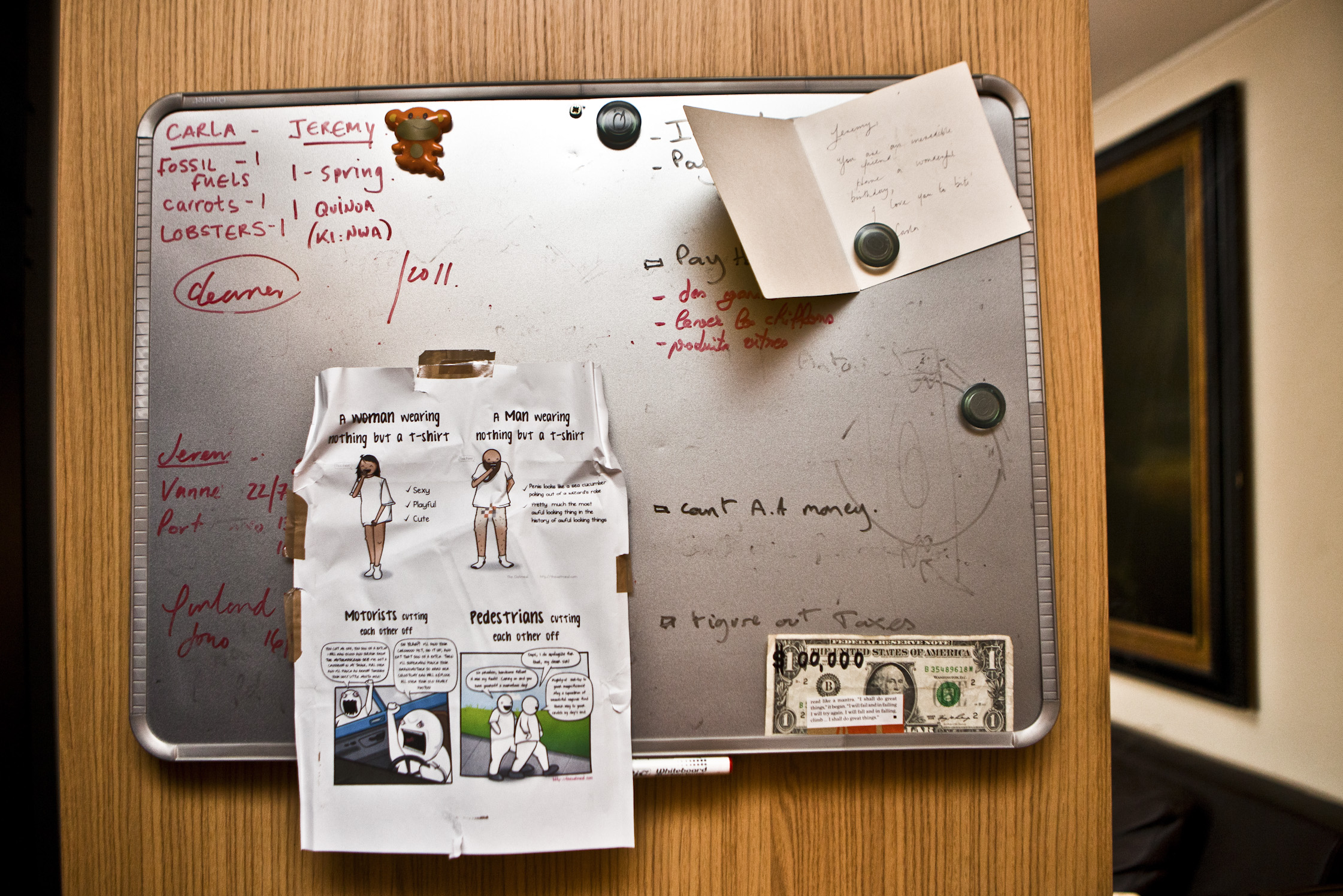

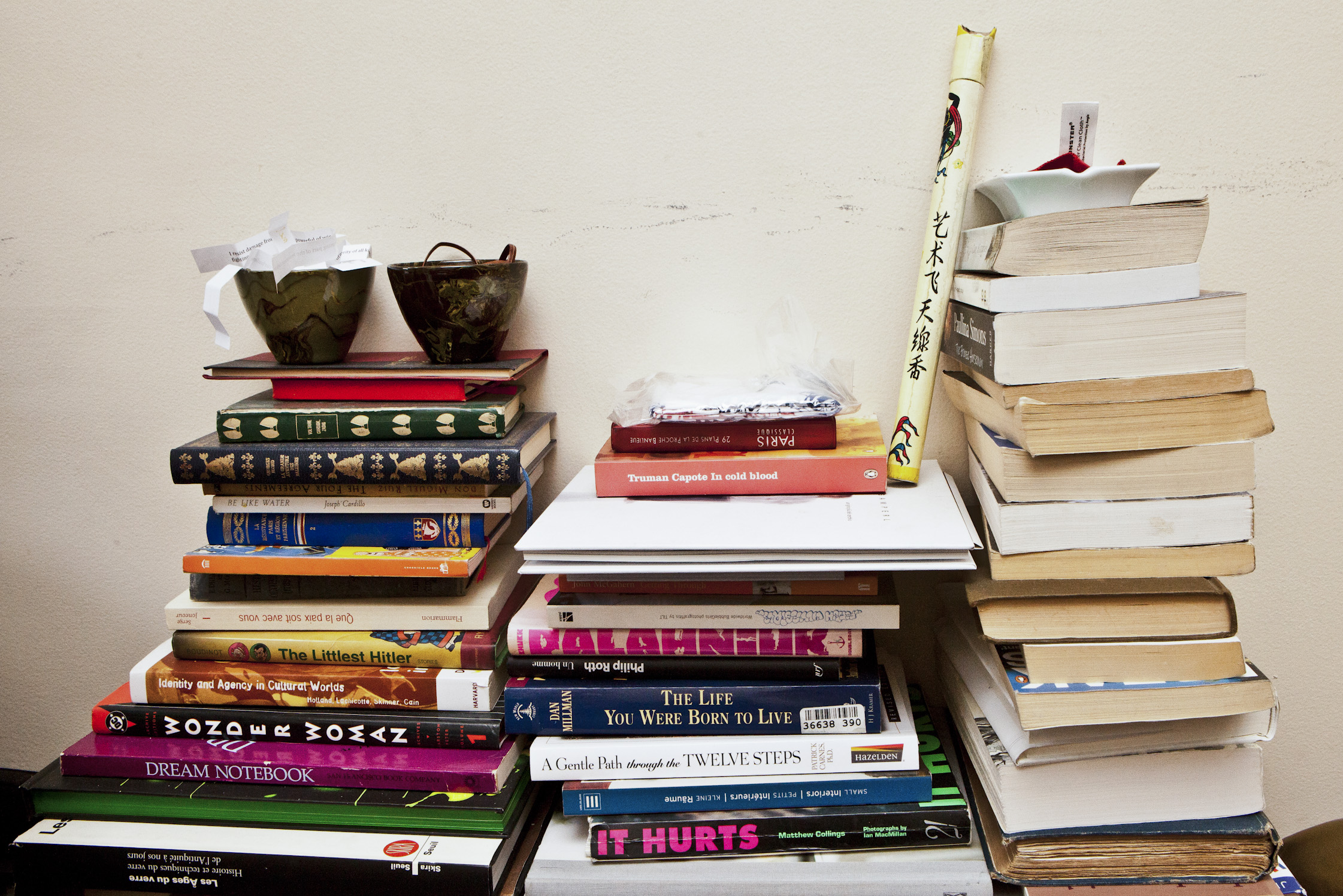

How would you describe your apartment? Are there objects with a particular meaning or of value to you?

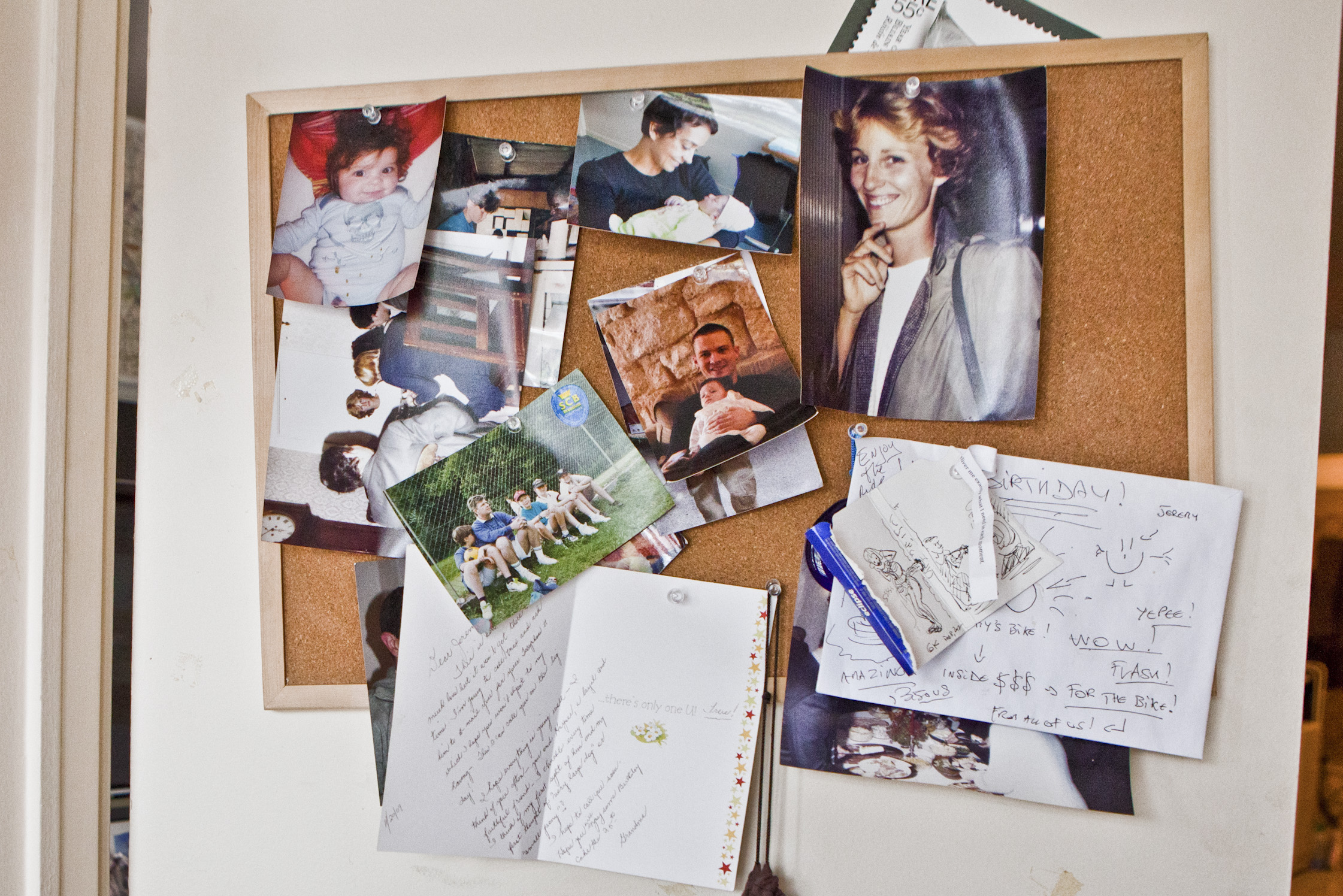

I like to be surrounded by my work, pieces that represent my story. I also really like to be comfortable. The apartment is tiny but at both ends of it there is a sofa and armchairs. The experiences I overcame told me to take care of myself and be relaxed. Behind this door there are three pictures of my parents. This is all I have left from them. I am not a material guy. I’ve lost everything at several occasions in my life. I used to have furniture from my parents and kept it for years. At some point, I realized that it was only furniture and I threw it all away.

All I need I carry inside me or on me. I cannot lose a thing. But that doesn’t mean that I don’t appreciate some comfort. I cannot wait to move in my new house in the countryside, far from the city, in a quiet spot. I feel a bit like a lonesome cowboy, who lost along the way his horse, his dog and still continues to walk. Now I want to build something and I feel this house is a very good starting point.

After our talk, Jeremy takes us to his stock on the outskirts of Paris. We arrive at a storage box facility; he leads the way through long corridors and opens his box. 14m3 closed by a lock from the inside, pieces ready to be shipped, tools, colors and blowpipes. This box matches his nomadic lifestyle, always on the go, with little stuff and few attachments. The new house seems to be very expected and would give him “the space to create something new.”

Thank you to Jeremy for that afternoon. Check out the video “BIG,” which features a remarkable project by Jeremy and his team. Overall information on his work can be found on his website.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on their site. To visit the special picture selection, go here.

Interview: Léa Munsch

Photography: Sarah Skinner