Numerous strips of paper, spattered with paint and colored with brush strokes collect together in a small, untidy pile in Titus Schade’s studio.

No, it’s not art. Taking a closer look it turns out that the whole heap is bits of masking tape that the painter has used to paint on the canvas with oils and acrylics.

By contrast to Schade’s eclectic studio, his work has – at least at first glance – a geometric, cold appearance. The accurately drawn surfaces of his paintings exhibit a contrast with the more loosely painted parts that highlight its artificiality. “By not throwing out the sticky tape, the pile has grown into a sort of companion,” the born-and-bred Leipziger explains with a bright smile.

The artist, Titus Schade, takes us on a very personal tour through his home city, Leipzig. He wants to show us the places that have inspired his work. In the early ‘00s, the work of Neo Rauch, Titus’s artistic mentor, was particularly prominent in the hype surrounding the city: the Leipziger painters would be catapulted onto the world stage of the international art market. From Titus’ studio in the area of the spinning mill, he’s made a small tour route for us, which will take us on a trail through Leipzig’s jungle of culture. Titus is received as a much welcomed guest, but he also offers us a glimpse into Leipzig’s “Off-Galleries” and an unparalleled view of his city.

Titus Schade’s Studio at The Spinning Mill

The spinning mill stands in west Leipzig, in Lindenau. Covering ten hectares of land and with twenty multistory buildings, it was one of the largest spinning mills in mainland Europe. The area was untouched from the Second World War because the bomber pilots had supposedly believed that the large, grassy roofs were just meadows. With production ending at the mill in 1993, the place opened for painters. Neo Rauch was one of the first artists to move his studio here, and Titus Schade also established his workshop in this space.

Titus relishes being in close proximity to other artists, “The spinning mill is like a city within a city – there is something village-like but also with clear boundaries! You continuously bump into your colleagues, but, on the other hand, you can easily keep out of each other’s way.”

This so-called “village life” is also illustrated in the exhibition space. We visit a show curated by all the artists who work in the area of the old spinning mill; Titus’ work is also in this exhibition.

-

Titus, thank you for showing us around your studio. First of all, would you call yourself an artist or a painter?

I don’t like the expression “artist”; I have a problem with it. It makes me think of a magician or a circus performer. I see myself as a painter or a “picture-maker”. Painting is a slow medium. What I make isn’t completed in a second but, rather, it is created by hand over weeks and weeks.

-

You were born and grew up in Leipzig. Have you ever lived outside of Leipzig?

I have never moved out of Leipzig for a long period of time. In the beginning of 1989, my parents applied for an exit visa to West Germany, which, for me as a child seemed terrible. I would have to leave all that I knew. But then, as a result of the political developments they decided, instead, to stay here. I believe that because of this, I feel very connected to my roots here. But of course, what I exclude here is the short time periods I’ve spent elsewhere.

-

What have you experienced are the benefits of Leipzig?

At the moment, the world is looking towards Leipzig – it happens here a lot. Leipzig is simply a good area with a lot of free space that is given over to work. Not too big, not too small.

In some ways, the city is quite slick, but, in other ways, there are also the shabby corners and backstreets that I knew as a child. You’d think that you’d know this city from every angle if you are born and brought up here, and yet you’re always surprised by hidden spots. The really special thing about a city is not something that can be put into words. Leipzig is a place of retreat; people just have so much space here. It is also very much alive. That offers a great contrast.

-

In the ‘00s, the Leipzig School experienced an unparalleled international boom, for which Neo Rauch was one of the figureheads. What is special about the painting-training in Leipzig, which could explain the hype surrounding the city’s art scene?

The question as to why the boom happened cannot be answered in one or two sentences; it’s a lot more complex than that. But yes, I can try to highlight what was special in the training that’s given at the HGB (The Academy of Visual Arts, Leipzig). Before anything, the foundation course was really focused on handcrafts. We have developed a really down-to-earth attitude regarding the teaching and the academy. I think of the life and nude drawings, teaching the anatomy and courses in various printed media and workshops. The foundational crafts of painting skills are prioritized from start to finish.

When someone begins their studies they want to paint a huge painting from the start. But the students must spend their whole time sketching instead. Sometimes, we worked for seven hours a day in front of a life model and the professor looked over our shoulder every half hour. When you thought you’d done a really good sketch, it would be immediately pulled to pieces. The constant criticism, which we received both from the others in the class and from the professor, helped us to exercise humility when practicing our art and learning our craft. Similar mechanisms were also in place during the tutorial consultations with Neo Rauch, who would see upon entering the studio, where the mistakes are in a piece of work.

We stand in front of a canvas, upon which various, individual images are arranged. The Petersburg Hanging offers Titus Schade, the protégé of Neo Rauch, a reference for this image series. The style originates from the Russian Hermitage in St Petersburg. Layer upon layer of individual images are placed on top of each other demonstrate the wealth and the variety of a collection.

Shade uses this hanging to position different painting styles side-by-side, from the very figurative to the extremely abstract. For Schade, the canvas is a sort of platform, upon which things are arranged – similarly to a sculptor who assembles many items upon his model board.

-

What do you enjoy about painting?

I like to create my own order and be able to control things throughout production, even within the smallest space on the canvas. But there is also something very playful in painting. I work straight onto around 30 canvases, and the idea becomes quite informal. When handling a small image, you should work more effortlessly and quickly. Often, random things come out of this process, which were perhaps not planned for on the larger scale. I like some of the small smudges on one of my pictures, they really stand out for me because I had rubbed that spot with my thumb.

-

Why do you want your paintings to sometimes appear cold and artificial?

I like this artistic style in my work because then, when “warm” or natural places are painted, they will appear better or stronger to the viewer. A contrast lies within the scene and that excites me. The canvas is like a window, scenery, a film or a single-shooter video game.

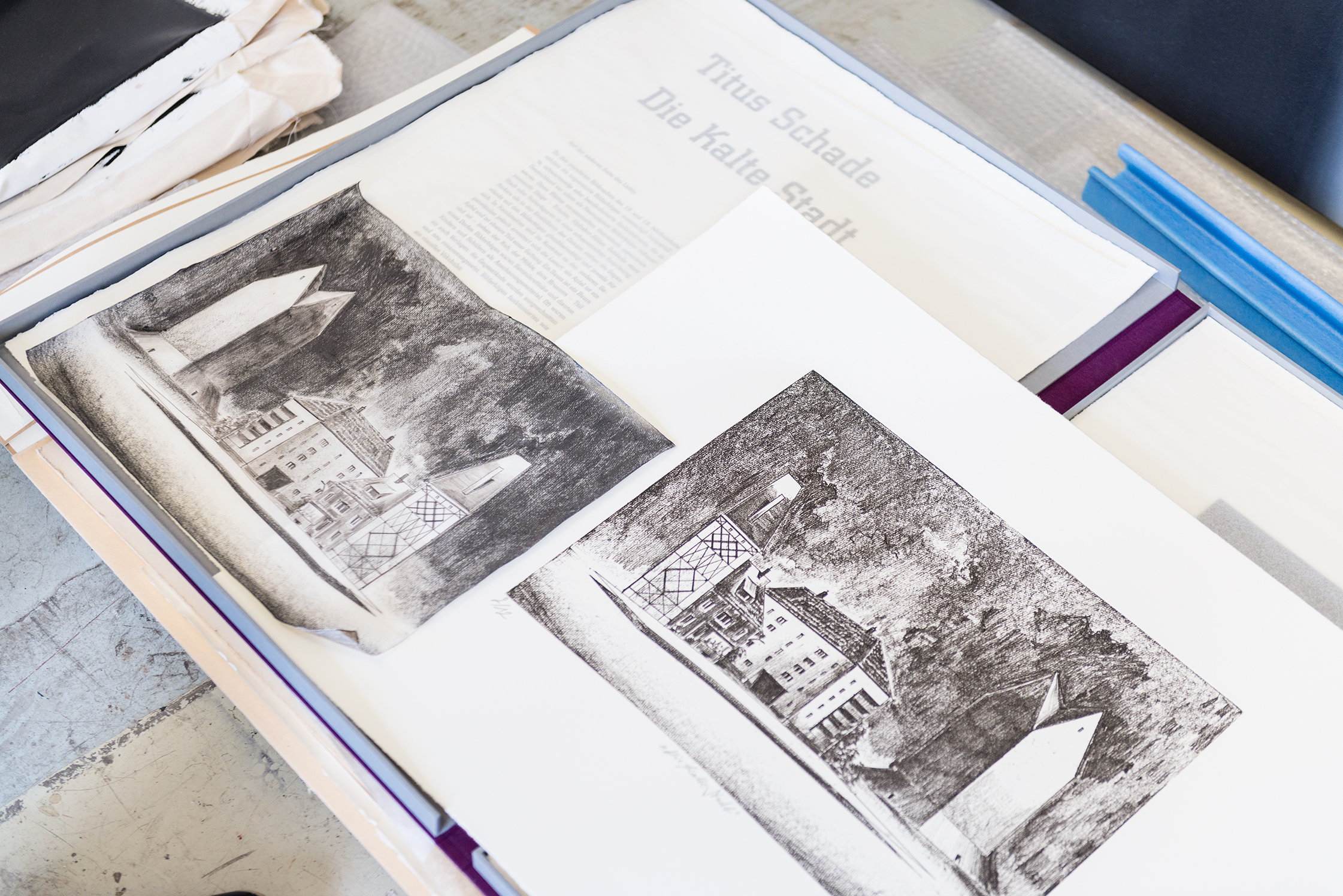

Visiting the Engraving Studio of Vlado and Maria Ondrej

A lot is printed in Leipzig and there’s always been a long tradition of that here. Vlado and Maria Ondrej’s workshop is situated very near Titus’ studio. Here is Ondrej’s “Cold City”, an edition that was produced with Titus’ etchings. Maria Ondrej works with the utmost thoughtfulness. “If people knew how much work was involved in this then people would treat these graphic cassettes a lot more seriously,” Maria Ondrej claims. Together with her husband, and ex-teacher, Vlado, Maria manages the engraving studio.

At Eigen + Art Gallery’s Leipzig Branch

The founder of Eigen + Art, Gerd Harry (‘Judy’) Lybke, was once the smartest gallery owner and businessman managing painters during the hype surrounding Leipzig. In the Leipzig branch, which can be found in the area of the Spinning Mill, we meet Elke Hannemann, who manages the on-site gallery.

It’s a bright, cavernous room with concrete floors, which makes large-scale pictures appear diminished in the space. In a corner sits a metal cabinet, in which images are archived in a grid system. Elke values Titus’s ability to reimagine real spaces into his own style, “It’s pure Geometry: this house, which appears in a lot of Titus’s work, is not a lot more angular than the houses in reality. There’s a lot of concision in his images, it’s just composition.”

Old Storehouses on Lindenauer Hafen

Titus drives through the radiant sunlight directly towards three huge, old, empty storehouses on Lindenauer Hafen; it is the one that is referred to as the “Pointed Gable House” in which he exchanges his work. Silently, Titus shows us this space.

-

You’ve depicted the storehouses and other real places in your work. How come?

As a painter, I have found my purpose: to communicate things. What I attempt to do is to create order within a cosmos of images. But what I really want to do is certainly not that apparent in the image. It is there for the viewer to find out for themselves. I don’t like to draw up guidelines or list instructions. I work with inspiration, but I keep away from photos and other media. I dare the paintbrush and trust the painting to express all that they can, all that I want to say.

-

Are you often by the canal?

I ride by the canal on my bike every day, on my way from home to the studio and back again. But you can only really get a feel for this area through relaxing strolls.

Emphasis on Painting at G2 Gallery

The G2 Gallery – which houses the Hildebrand collection with a focus on painting – is managed and curated by art historian, Anka Ziefer. Art from Leipzig remains as the heart of the collection. Among others, there is work from Neo Rauch, Hans Aichinger, David Schnell, Matthias Weischer and Tilo Baumgärtel. “People want to see paintings; that is an important tradition. Painters have occupied themselves for thousands of years, trying to find new representation,” Ziefer remarks. You can also find Titus’s work in the collection. “This canvas is very important to me. I actually wanted to keep it for myself. But Steffen Hildebrand could acquire it because I think that it is in very good hands here.”

Old Master Paintings and Contemporary Art at the MdBK

The MdBK (The Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts) principally exhibits painters. Here, Titus meets Marcus Andrew Hurttig on a tour, who is one of the museum’s scientific staff members. The collection that is housed under the roof of this imposing building spans a chronology from the old masters all the way to contemporary works. Over impressive staircase hangs a gigantic mural by Jonathan Meese. “There are very strong pieces from the likes of von Cranach, El Greco, Bartolomeo Manfredi, Peter Paul Rubens and Caspar David Friedrich here. But then, you can also see contemporary painters as well,” Titus points out.

GfZK: Museum of Contemporary Art

You can find this museum in Leipzig’s music neighborhood, spitting distance away from Titus’ old academy, the HGB. The Herfurthsche Villa stands diagonally on the site, connected to the Clara Zetkin Park. A modern cube was added to the exhibition rooms in 2004, a functional place with moveable partitions.

Ortloff Art Space: A Forum for Emerging Artists

His half nightclub, half exhibition space is how Ortloff gained local celebrity status. Founded in 2007, it was one of the first places where Titus exhibited. In the beginning, exclusively Leipziger Artists were exhibited here, with its unmistakable proximity to the HGB: but by now, the art space exhibits art from across Germany. Now, Ortloff has evolved into an integral part of the Leipzig Art Scene. The Ortloff Art Space not only provides a forum for young artists and the OFF-Art scene, but is also a reference point for the Lindenau district. For a once working-class district, the area is quickly experiencing gentrification.

Passing by the Monument to the Battle of Nations

Titus insists on pausing here. The impact of the 300,000-ton monument still has visitors to this day. Despite the impetus of militarism and nationalism, this place radiates a peculiar tranquility that we can reflect upon, which is why Titus so wanted to bring us here. Established in 1913, the monument was built to a design by the architect Bruno Schmitz. It sits upon a stone platform and is surrounded by an artificial pond. It was built in the battlefield of the 1813 Battle of Leipzig, which resulted in Napoleon’s defeat. Today, we overtake a jogger on the steps up to the monument. Strangely, this doesn’t disturb the calm. “I’m also not here that often, but the monument is simply one of the most important sites in the city, and the place has an almost magical magnetism,” Titus explains.

Ending the Day at Blue Pearl Bar

An old, shabby Hyundai stands in the middle of the Blue Pearl Bar’s beer garden, where an array of tables, chairs and bar stools are collected into mismatched groups. The drinks are very reasonable. The young men who work behind the mobile beer wagon welcome Titus with warm words. The front bar area is now officially closed, but we must take a look. Most of the decor is red faux leather barstools, velveteen, animal prints and silver foil. This is the Leipzig for the indefatigable. The strangest of the city’s characters gather here, to see and to be seen. But it is also a place to have a quiet drink in peace – so long as you come early enough!

And it is here that our tour of Leipzig comes to an end. The artist, Titus Schade, has shown us the places that are just as important to him as his work itself: the letting go and the making of new friends leaves us feeling exhilarated.

This portrait is part of our ‘Guided and Curated‘ series produced in collaboration with MINI Germany. Selected individuals give us insight into their cities through guides tailored to their area of expertise.

Discover more stories from Leipzig.

Photography: Tim Adler

Text: Nella Beljan

English Editor: Aggi Cantill