With Penny Martin at its helm, The Gentlewoman has emphasized genuine storytelling since its launch in 2009. Prior to the coronavirus lockdown, we met up with the revered magazine editor in London to discuss viable role models, slowing down, and trusting her instincts.

The leafy landscape of Gunnersbury Park in West London’s suburb of Ealing, with its grand, ivory-colored estate rising atop a tiny hill, seems desolate on this Friday afternoon. As we meander along the soggy trail towards a coffee shop in the heart of Ealing, Penny Martin tells me about her recent run-cum-interview with fashion designer Paula Gerbase through central London’s Regent’s Park. That Martin mastered an elaborate 89-minute-interview while catching her breath strikes me as impressive, but is also characteristic of the first and only Editor in Chief of the biannual fashion and women’s publication, The Gentlewoman. Whip-smart and remarkably attentive, she knows all the tricks of her trade. An avid runner, she tackles a route linking her home with Gunnersbury Park, crossing through Walpole Park, at least one morning a week. Normally distinguishing between her professional and personal lives, Martin feels pleasantly removed from the high octane rituals that working in fashion can entail, with many of her fellow residents being unphased by her acclaimed position in fashion media. She mentions that we passed someone from her running club earlier, noting that this person would not be remotely impressed if she knew about Martin’s career.

To the fashion industry, Martin is a publishing powerhouse, a characterization she shrugs off nonchalantly. “You can say [The Gentlewoman] has been influential. None of us are in this to cultivate a personal profile based on power.” Hailing from St. Andrews, she still speaks with a distinct Scottish accent. Her impetus is to run a magazine that is cerebral of fashion, personhood, and long-form journalism, her personal taste being inextricable from what the magazine represents. Every issue has a cast that resembles the guest list of a good dinner party, made up of a wide range of characters bringing different views and experiences to the table. Martin invites a bona fide icon, a newcomer who shakes up the conversation, and someone of the moment. Cindy Sherman meets Lizzo and footballing sensation Lucy Bronze; Margaret Atwood and Kara Walker rub shoulders with emerging actor Julia Garner and pop star Charlotte Adigéry. With her approachable warmth, Martin makes for the kind of host that everyone feels comfortable around. Within the pages of her magazine, she creates the space and comfort for a role model like Alison Janney to talk about not enjoying her success until her fifties, and for Martha Stewart to share her prison experiences.

“I’m more of a 400-meter runner when it comes to creative projects.”

While many other fashion journals regard readers as consumers before anything else, this treatment is largely absent from the pages of The Gentlewoman. The magazine’s unique selling point is its “wilful strangeness and desire for the esoteric,” which is translated into long-form writing that is as colorful as it is intimate. Martin recalls a recent pitch in which a journalist highlighted a potential interviewee’s beauty. “I remember her laughing when I said, ‘I’m not really bothered about [her beauty],’ not really thinking about what I was saying,” Martin tells me before explaining, “We’re not particularly interested if she’s the cool girlfriend or the fashion icon.” For The Gentlewoman, iconicity is found in places both unambiguous and unexpected—in Beyoncé, who graced the cover of issue seven, as well as in the women that readers forgot they loved, such as British actress Angela Lansbury and Icelandic singer Björk. The magazine chose to profile British singer Adele in 2011, a rather surprising cover star at the time. “I’d heard that our magazine was being slapped down on the desks of other women’s magazines’ editors afterward, saying: ‘Look, what was your problem?’ Of course, we know what the problem was: that they wouldn’t have touched somebody that was seen to be ‘plus-size’.”

Martin’s first formal contact with visual culture was through her mother’s art books, including an art book of nudes. Jennifer di Folco, an art teacher, would use the books to keep Martin and her two brothers quiet when she had company. But while art permeated her family home, Martin was not fully aware of fashion until she moved to Glasgow to study art history, becoming drawn to vintage clothing in a bookish sense. An undergraduate degree under her belt, she later completed a postgraduate diploma in Art Gallery and Museum Studies at Manchester University before pursuing a Ph.D. in fashion photography at The Royal College of Art. She was 26 when she moved to London in 1998. Researching the “deeply unfashionable end of fashion photography” during the ’90s, an era that predominantly feted grunge and loathed the stylized photography of the ’80s she was studying, her thesis applied Thatcherism to photography, exploring how the Iron Lady’s ideology, appearance, and political relationships within the fashion industry were manifested in Vogue.

Martin admits that she does not consume fashion magazines in the way she used to. “It’s my job to be aware of what’s in them, but I can’t suspend disbelief in the way that with a magazine at its best, you’re passively consuming another perspective and you’re not exercising any critical faculties. Once you’ve tipped over to the dark side and you can see the mechanics behind it, you see behind the Wizard of Oz’s curtain.” Martin interrupted her Ph.D. when her brother Ryan was killed at 25 following an attack on the streets of Glasgow—she could “not bear the solitude of completing the academic work.” British photographer Nick Knight offered her a job as the editor of his new fashion platform SHOWStudio, after visiting an exhibition she had curated. In her new role, she found stimulation in the “sunny optimism” of production work and a community of people working toward common goals without hierarchies. “I got rather addicted to the short-term delivery of making fashion communications instead of giant, long-term projects that take forever to execute. I’m not really a marathon runner. I’m more of a 400-meter runner when it comes to creative projects,” Martin notes.

After seven years at SHOWstudio, Martin returned to academia for a short stint in the research department of London College of Fashion, as chair of fashion imagery. She was trying to push herself back to what she thought she ought to do—“the thoroughly sound, distinguished goal, the respectable route” that she had set for herself as a teenager—but soon realized it wasn’t the right path. She recalls the advice of a former coworker at the college, the curator Judith Clark: “Do what gives you pleasure.” At the time, the recommendation sounded exotic and far-fetched. In hindsight, it is exactly what she went on to do by listening to herself. Though she never felt outside pressure from her parents or other parties, it was like giving up a childish sense of trying to please everybody. “I needed a lot of evidence to prove to myself that the other thing, fashion and journalism, was making me happy. I’m pretty effective once I’ve decided to do something. I’ve got such stamina that when a project is on the road I can risk losing touch with my own needs, if I’m not careful.”

Before joining London College of Fashion and while still a member of SHOWstudio, Martin traveled to Amsterdam to meet with Gert Jonkers and Jop van Bennekom, the Dutch publishers of the men’s journal, Fantastic Man to discuss her editing a new women’s title, The Gentlewoman. Uncertain about her next career move, she turned down their offer and joined London College of Fashion instead. Six months later, she was relieved to learn they were still keen: “They saved my life because I think I would have been depressed. [The research role] wasn’t right for me.” As frightened as she was about the prospect of taking on print—“I genuinely had no idea how to do it”—she knew it was the right move to work with them. The initial phase of their collaboration was fun and wild. She recalls being raucously drunk with van Bennekom at a fashion show party in Pierre Hardy’s studio, laughing at the memory of leaving her coat behind. Her Instagram profile picture—Martin’s face radiating with a smile as her blonde locks fly in the air—was taken that night. “Their world was a bit more exuberant and a bit funnier,” she says, noting the contrast with the very serious, reverent museum demeanor she had known. Her new team got to know a rather “weird, formal girl,” she says. “Suddenly, with them, I felt a certain amount of freedom, in a way.” With production periods of 15-hour-days and no weekends looming ahead, mutual appreciation was indispensable to the team.

The Gentlewoman launched during the 2009 recession. The heightened economic risks left Jonkers and van Bennekom unperturbed—Martin describes them as two very careful, canny entrepreneurs who are clever with money. To this day, she has never needed to safeguard anything but the quality of the magazine’s content, prioritizing adequate compensation for the people involved over fancy hotel budgets, and making sure the publication is worthy of her subjects. Working in the civil service, in museums, had taught her good and bad management. Working under the two progressive publishers, she was given an enormous amount of opportunity, freedom, and support. “They have quickly allowed me to stand in front of what started as a collaborative project—not only to represent it but to take some credit for its successes. How many other male publishers and editors would have done that?”

“I remember growing up in the provinces in Scotland, I couldn’t imagine having a media job.”

What’s her secret to empowering her team, which has remained almost the same for an entire decade, I ask? “Our industry is full of people who don’t listen to others. I want to be around clever people so that’s what I appoint; really hardworking professionals who deeply care about whether a story worked or whether we’ve got a typo in there.” The painstaking attention to detail has paid off: The dwell-time of The Gentlewoman’s online library is enormous—four to six minutes—while a good number of the magazine’s back issues are sold out. The Gentlewoman doesn’t rely on themes and only covers individuals once. Does its commitment to fashion ever undermine its agenda? “Exploitation can come in lots of different forms. Fashion can be a tricky area, but I don’t see it as an intrinsically nefarious thing. It just needs to be very well-managed,” she answers. The Gentlewoman does not portray women in a sexualized or commercialized way. No crass crotch or overly profit-oriented bag shots that remind the reader why women started to hate women’s magazines in the first place. The cover featuring Beyoncé, which marked a big shift for the magazine, conveys an introspective and warm version of the incandescent megastar: In the black and white picture, she wears a simple black, round-neck shirt tucked into a patterned A-line skirt, her hair tied back in a ponytail, her piercing eyes appearing to see through the camera. “It felt like a giant compliment to the team— that a team as demanding and specific and who, frankly, didn’t need us, would be prepared to let us contextualize and represent Beyoncé in a different way from how she would normally be represented,” Martin says. It took a lot of wrangling to convince Zadie Smith, who is knowingly skeptical of women’s representation in the press, to be on the cover. The result portrays the ingenious novelist in a measured yet sensual way. All of the aforementioned covers were styled by the magazine’s fashion director, Jonathan Kaye, whom Martin describes as an extremely eloquent image-maker.

Each issue inevitably reflects the team’s taste, with Martin and creative director Veronica Ditting barring the doors to unwanted directions. “It’s like a running stream of consciousness because the magazine is made up of people you’re fans of. Naturally, we don’t always agree but there is an overall commitment among the team to certain values that help determine the casting vote.” Megawatt celebrities are balanced with unexpected, even obscure figures. “I just started laughing!” she says about seeing the Angela Lansbury cover for the first time. Wearing her own rose-colored silk blouse, red pearls, and oversized glasses, it related to how clever the picture was. The magazine’s covers not only give protagonists the picture they deserve, but also carry the conversation for months, if not years, past their release dates. They underpin the magazine’s mission to be aspirational and cerebral. “Growing up in the provinces in Scotland, I couldn’t imagine having a media job. It just felt so remote, the people I was looking at on TV couldn’t possibly be me.” Martin asks me if I knew of Jane Street-Porter, the coarse and quite sensationalist journalist with a cockney accent; the kind of woman you would not expect to see on the BBC in the ’80s. “I used to think, maybe I could do that. Still to this day, when I’m out of ideas, I think, what would Janet do?”

“I don’t want to read about despair and I don’t want to be a publisher of despair.”

The magazine executes its optimistic vision of social change with warmth and kindness and leadership—and does not get “dragged into a tailspin of dark conversation and rhetorical questions that can never be answered.” Martin remarks, “That is dangerous, culturally.” She despairs of conversations that “inevitably end back on the same topic” and often end with a shrug and shake of the head. Personally, she can’t afford to languish. “I’ve got a responsibility in terms of what we reflect. That’s how I would run my family: We’re not ignorant about the terrible things we know but we’re not going to wallow in them,” she says about the magazine’s need to be the North Star, focusing on tips and takeaways. “I don’t want to read about despair and I don’t want to be a publisher of despair.”

In contrast to the flamboyant, noisy, performative household she grew up in, she chooses to live a rather quiet adult life. Her father was a singer and besides art, there was always music playing, animals to be looked after (they had dogs, cats, rabbits, zebra finches, guinea pigs, chickens, “and for one night only, a wild cat!”), or her parents arguing. Once a month or so, she takes a sleeper train to Scotland, to the small fishing village of Cellardyke near Anstruther in Country Fife where she owns a little house by the sea near her mother’s home, to recalibrate. The resources she invests there are something of a post-Brexit solution. Somehow our conversation veers towards astrology, and into stepping outside one’s comfort zone. Today, Martin’s horoscope (she is a Leo), written by American astrologist Susan Miller whose predictions she reads daily, encourages her to seek financial stability. Did she intentionally reconnect with her roots? It wasn’t on the agenda, no. “I’m a bit more aligned with the old left politics of Scotland than I am with politics down here [in London]. You want to be on the right side of history, right?” In September 2019, she was elected to the National Trust of Scotland, something she is very excited about, especially as more locals stay loyal to their origins, which she finds reassuring.

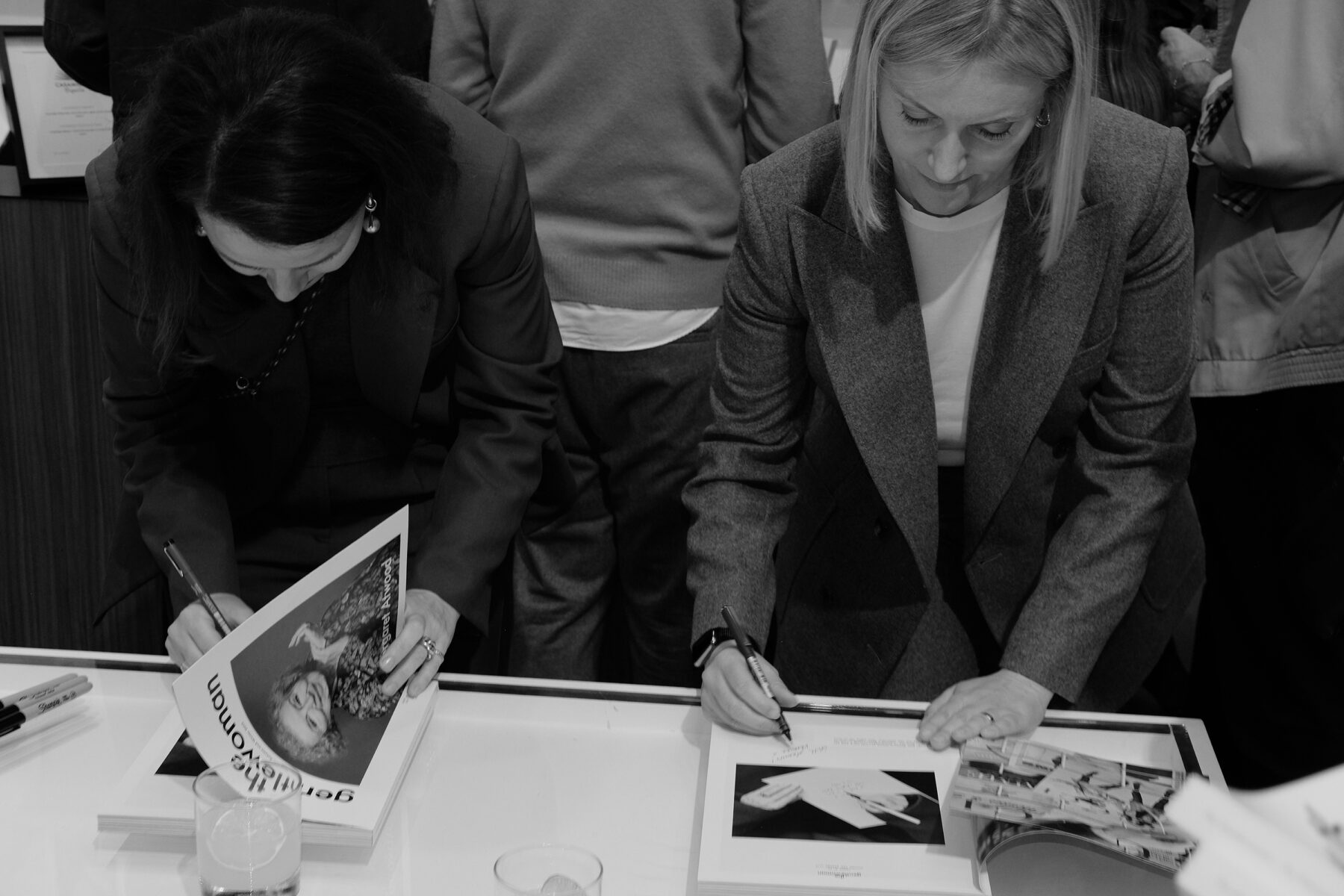

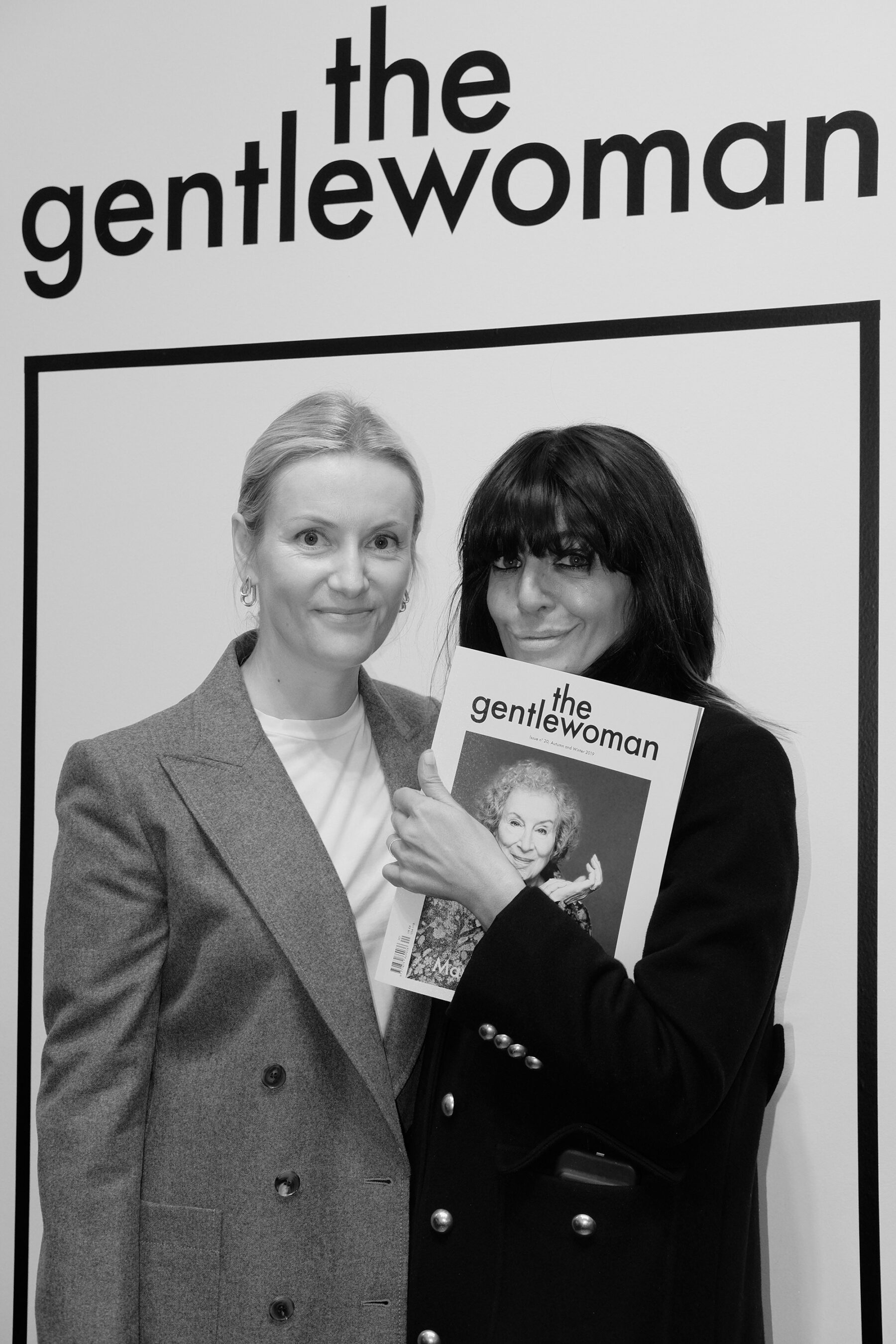

A few days after we met, The Gentlewoman revealed that the novelist and poet Margaret Atwood would be its next cover star. Over email, Martin tells me that she had to fight for this icon, whom she considers “the perfect summation of what we’re trying to achieve with The Gentlewoman: clever, upbeat, no-nonsense, and a walking repository of the most surprising literary quotations.” I immediately associate the first three attributes with one other person: Penny Martin herself. Martin has redefined the concept of linking fashion and personality-driven journalism, and in a way that is deeply rooted in who she is—a driven, confident editor as well as a receptive, compassionate woman who follows her gut feeling. “You’re constantly putting yourself into the future,” I remember her saying over tea and cake in Ealing. “Stuck in a project you can’t control and it goes on forever, that’s the worst. The lightness and the pace and the momentum, the years pass fast, but that’s because you’re enjoying yourself.”

Penny Martin is the London-based editor of the biannual women’s publication The Gentlewoman. Having worked at the magazine since its very first days, she is integral to its editorial direction, having commissioned profiles ranging from Beyoncé to Margaret Atwood. The most recent issue of the magazine features South African middle-distance runner and Olympic gold medalist Caster Semenya.

Text: Ann-Christin Schubert

Photography: Tina Hillier