For centuries, exceptional women were ignored by patriarchal establishments, and those that gave them a voice. Raising awareness for the challenges female designers and architects have faced throughout history, Libby Sellers’ book Women Design is a celebration, at last, of just how influential they were.

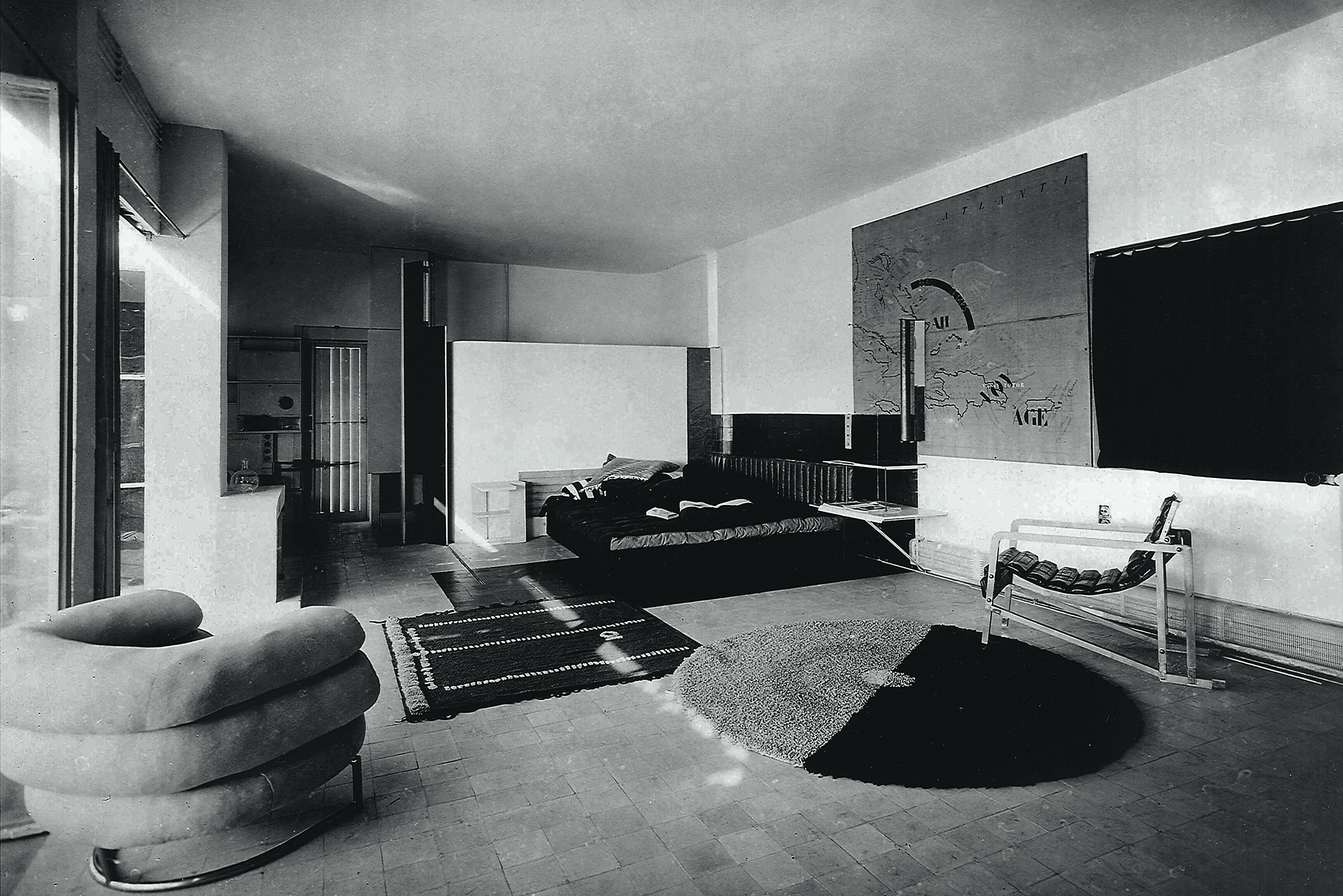

Eileen Gray completed her work on one of the 20th century’s masterpieces of modernist architecture in 1929, aged 51. It was called E-1027, and it was a seaside home that she originally planned to share with her husband, the writer and architect Jean Badovici. While it was intended as a joint project, Badovici’s job at an architectural magazine took up his time. E-1027 incorporated some of his ideas, but ultimately it was Gray who oversaw every element. The three-year project’s design and construction was developed according to her principle that “a dwelling is a living organism.” Gray continually directed her design towards addressing the needs of the occupant. Complete with a set of Gray’s furnishings that are now, too, heralded as exemplars of modernism, her focus on the comfort of the user was actually a far-cry from the narratives surrounding the movement at that time—as was her gender.

By the time the building was finished the relationship between the two had soured, and the pair split up. Badovici kept the house as his own personal residence, which he shared with his new partner. Gray had created a building with a monumental legacy in modern architecture—but it was a building she could not live in, and a legacy that, for many years, Gray was denied.

A ‘female architect’ seemed almost a contradiction in terms at that period, and there was no precedent for a building created by a woman in the modernist style. For an untrained female to design one of the 20th century’s greatest buildings? Impossible. After Badovici died in 1956, France’s Union des Artistes Moderne honored E-1027’s architecture as Badovici’s work—and his alone. Gray was only credited for the furnishings. It is not that there were no architects aware of Gray’s role in the building—indeed, modernism’s architectural pioneer Le Corbusier wrote to Gray to express his intense appreciation of the house’s “rare spirit.” But no one chose to defend her work on the building.

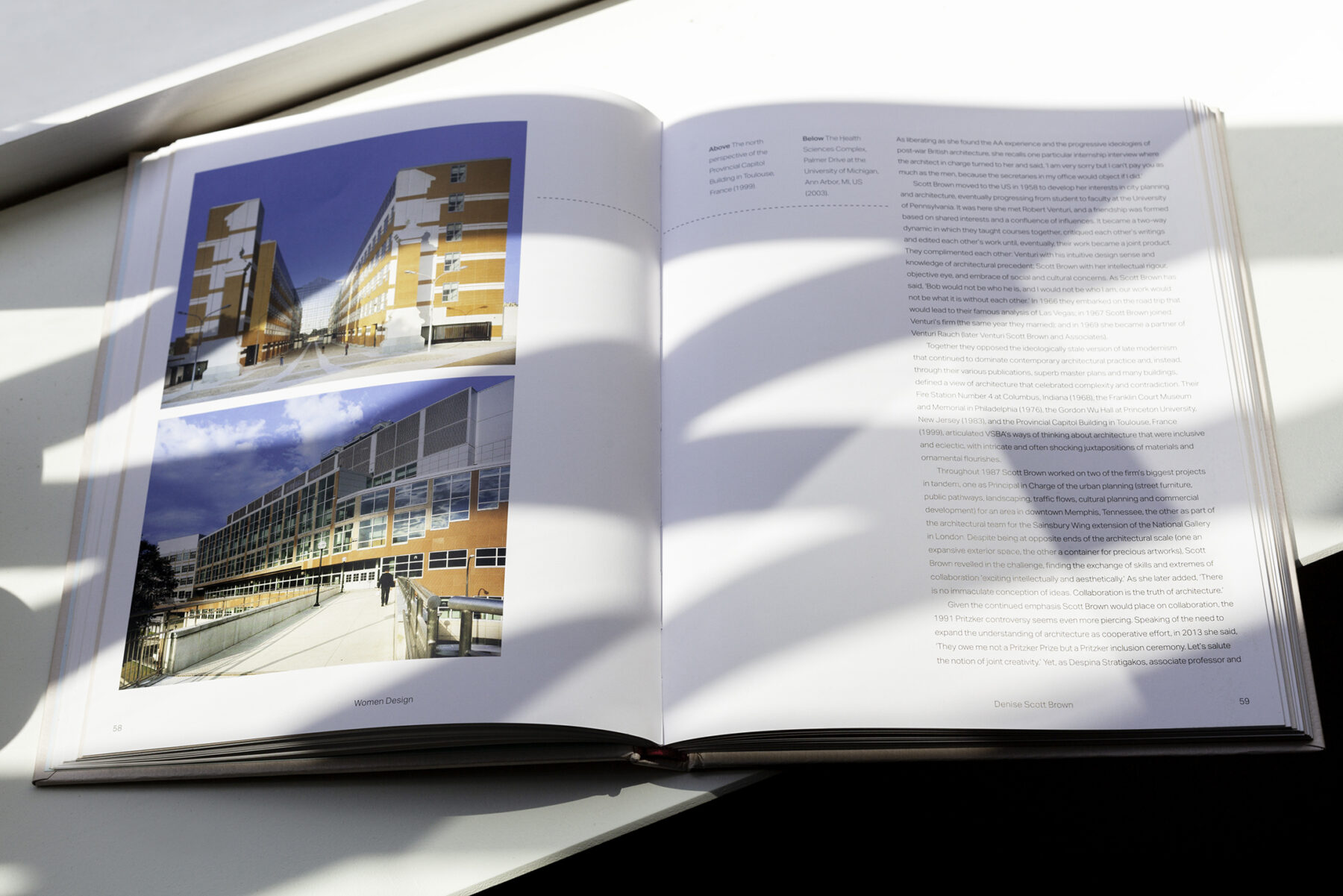

This is just one of the tales of female design described in Libby Sellers’ new book, Women Design. Among the 21 different profiles featured, the stories range from historical to modern examples of female success in the design industry. Each one examines the singular trials women have faced and continue to face in their field. However, while historical industry bias is addressed in Women Design, rather than focusing on women’s marginalization the book focuses on the ways they excelled in every respect.

Contemporary examples include designer Hella Jongerius and Zaha Hadid, the first woman to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize. Her architectural career has been dubbed neither traditional nor easy. In turn, her expressive architecture that includes Rome’s art gallery Maxxi and Glasgow’s Riverside Museum was forceful, far-reaching, dynamic, and each building reflects the perpetual motion of contemporary life. Equally influential in her field, Jongerius challenged conventions of material appropriateness. Designing upholstery and ceramics among other products, she carefully explored the role of color in interior design and successfully introduced artistic standards to industrial production processes.

Moreover, the book also reveals the apparent sexism exhibited at the German design school Bauhaus in the early 20th century. The Bauhaus was one of the first state-funded art academies that actively invited women into its programme in 1919, with females outnumbering men 84 to 79 in its first year. And yet, in 1922, Walter Gropius placed a limit on female applicant quotes—he feared that the amount of women scholars would undermine the school’s credibility.

He reinforced the subjects at the academy as heavily gendered, where women were sidelined into textiles production while men were taught the more respected crafts like metalwork and architecture. However, it was women who modernized weaving techniques and who broke convention and made their way into the metalworking class through commitment and originality.

Many of the featured individuals, like Gray, had not studied at avant-garde design schools such as the Bauhaus or aligned themselves with powerful male mentors such as Le Corbusier or Walter Gropius. Mentored or not, trained or untrained, it’s within this context that we are able to consider the achievements of contemporary female designers.

Long dismissed by the world of design, women architects and designers finally gain recognition. With Women Design, Libby Sellers highlights 21 exceptional examples. They range from designer Ray Eames, whose influence on 1950s America was long shunned, to Patricia Urquiola, the brain behind socially valuable projects like The Bandas.

The book is published by Frances Lincoln. To learn more about it, visit Libby Sellers’ website. For more stories highlighting the importance of print publications, have a browse in our archive.

Text: Louis Harnett O’Meara and Ann-Christin Schubert

Header image: Scott Brown in front of The Strip, Las Vegas, 1966. Courtesy of Robert Venturi.