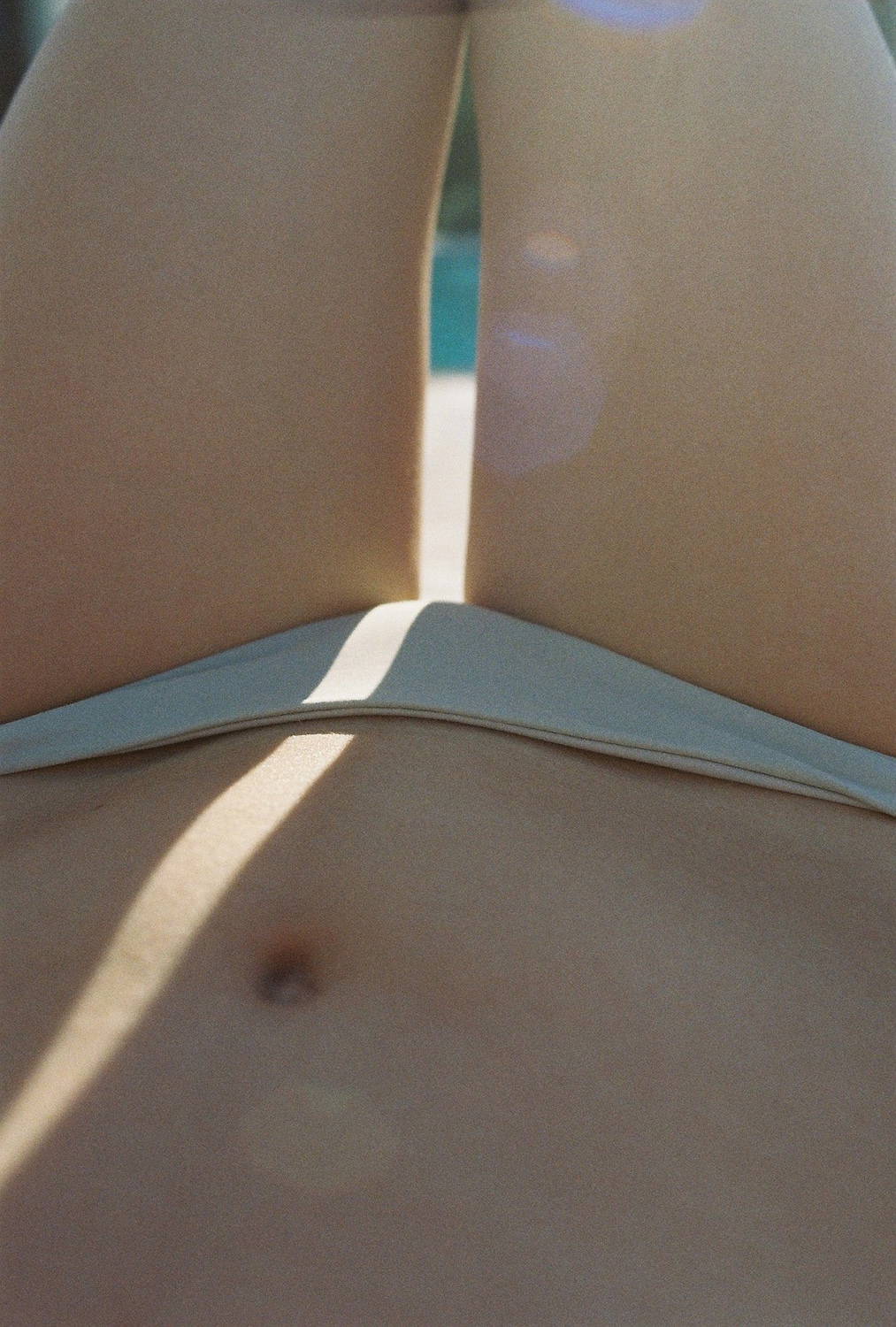

The first thing you notice about Eylül Aslan’s art is its clear focus on women. The Turkish born photographer, who’s now based in Berlin, positions her models in states of undress before cracked mirrors and distorted glass as a way of consciously objectifying the female form.

Often, their faces are concealed by hands and flowers, or their breasts are framed as a dim reflection in the screen of a laptop. Figures like these, fractured and bare, evoke rich discussions on gender and identity — topics that have grown increasingly important to the inhabitants of Eylül’s native city.

“I cried at my first exhibition in Istanbul,” Eylül says, over a table in her Berlin apartment. She has short black hair, dark eyes, and a face that is warm and expressive. “The opening was full of people I didn’t know. They came because they’d been following my work. Women came up to me and said, ‘We have to turn the mirror on ourselves, to look at ourselves and see if we are happy.’ Some even said, ‘I think I’ll go and divorce my husband!’ — radical things like that. It was very emotional for me to hear.”

The strength of such reactions, Eylül says, is due to the lack of open discourse about women in Turkish society. “We don’t have female role-models that women can attach to,” she argues. “Writers, actresses, sure, but there are few who will openly talk about the problems women face, or fight against them. They’re always thinking what would their boss or family might say. Turkish people are very concerned with what other people think, and when you’re a feminist, you’re seen as a witch or someone who’s bad.”

“I wanted to get rid of an inner darkness, and that’s why I started taking photos.”

Eylül’s connection with gender was instilled in her at an early age. “Blame my mother!” Eylül laughs. “She’s a complete liberal feminist, a very strong woman.” She’s also the Chief of Women’s Rights for the Turkish opposition party CHP. Her father, surprisingly, hails from the conservative north and is devoutly Muslim. “I think my family represents Turkey in a really nice way,” Eylül explains. “In Turkey, there’s a mix of everything — all different types of belief. When I was little, people were able to tolerate and accept each other. I was raised to accept others, but now, with Erdogan in power, it’s become more oppressed and more partisan.”

Like other elements of Turkish society, Eylül’s parents were unable to reconcile their differences, and eventually divorced. “I didn’t have any siblings and was on my own or around my mother a lot. Me and her are best friends and she’s had a big influence on me. She’s the one who gave me my first camera — so it’s all her fault,” Eylül smiles. At first the camera sat on a shelf, unused, but as Eylül grew and started to experience life as a woman in Turkey, the power of the lens to reframe a subject became increasingly important to Eylül’s self image.

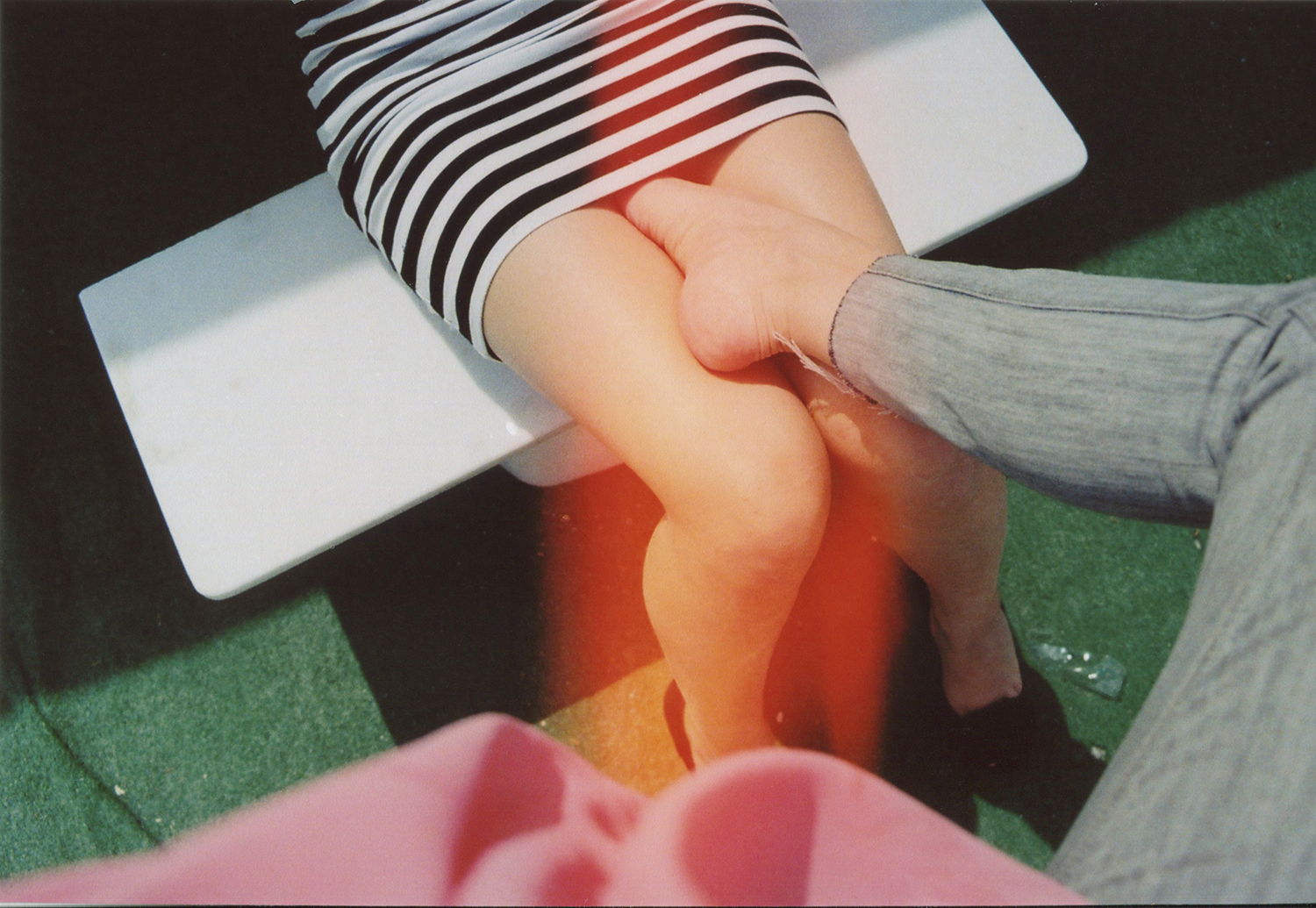

Istanbul, 2010, self-portrait: “One of my favorite photos and the first print I ever sold. I was always interested in the way people perceive periods as a taboo, how it is something to be ‘ashamed’ of, though it is one of the most natural things in life. I was also confused about my role in life as a woman and how difficult it is sometimes to express myself as one.”

Ankara, 2012: A portrait of my cousin who was the first muse I ever had, the first woman I photographed after myself. This was taken in her apartment in Ankara after she had moved out of my apartment. We lived together for 5 years.

“I’ve been sexually harassed more times that I can count. It wasn’t just when I wore a mini-skirt, it even happened when I was wearing pajamas. Women around the world are treated like objects, but it’s somehow more aggressive in Turkey. It’s not about the time of the day or where you are, you just walk in the street and someone thinks they can come and grab you,” she says. “I would go to university, someone would harass me, and I would come home and just feel so angry. I would think, ‘why am I not allowed to be who I am?’ I just want to wear a colorful red dress, for instance, and not receive all this attention.”

“I tried attacking them back, but it caused me trouble. Sometimes it’s a bigger guy or there are two men. You can’t win. But I wanted to do more than just cry about it at home,” she says. That’s when she rediscovered her camera, and would sit before a mirror, naked, or wearing clothes that men found obscene. She’d photograph herself, fully in control of the camera’s gaze. “It was an escape for me, a way to be who I was. I couldn’t wear a low top and run in the streets, so I did that in my room in front of the camera. It made me feel better. My photography is colourful and feminine, but it has a real dark side. I wanted to get rid of an inner darkness, and that’s why I started taking photos.”

At first, it was her own endeavour, but she gradually began to photograph others. “It started with me; I was the first victim. Then my cousin. Then my friends wanted to model for me. They asked, ‘Will you make sure that nobody recognizes me, or sees my birthmark or my face?’ They were worried about what other people would think,” Eylul says. The photos they took, simple nudes or uncovered bodies, were considered pornographic in Turkey. “There’s a lot of hiding in my work, which came from the fact that my models wanted to be hidden. It wasn’t originally my own aesthetic choice but it became my style.”

“Those were crazy days, and sometimes I felt that art wasn’t enough to save me.”

Eylül’s photography was an expression of herself, one that allowed her to explore her own sexuality. She remembers the day her cousin’s sister visited her room. “Eylül,” she asked, “are you lesbian? Why do you have only girls on your walls?” Eylül remembers her reaction, “I was like, ‘Oh! Wow. It’s true.’” Aside from a poster of a dashing David Beckham (for whom she learned English), her walls were covered entirely in women: magazine clippings of actresses and models. “‘Maybe that makes sense,’ I thought. I was never aware that that could be what I prefered,” Eylül recalls. “A woman and a woman — it couldn’t be! I hadn’t even thought about it until she said it. I was fifteen and with my first boyfriend at the time.”

Queer or curious women in Turkey have a hard time discovering other women, as Eylül can attest. “When you’re with female friends, everyone is hiding. You don’t get to see their bodies and you get really curious. For me, the female body was mysterious, even though I had one,” she says. “We have Hammams, the baths or steam rooms, where you see women naked, but I only went when I was young. I only ever saw my Mum and my cousin naked, and that’s because we lived together. It’s very simple psychology: when something is hidden or not allowed, you just want to do it. I wanted to know what people were so scared of. Why did they have to be hidden?” Her photography was a way to find out: “I could express my own fantasy world, sexual or otherwise.”

Berlin, 2014, model: “Distortion of the idea of what a woman is or how she should be. Different ways of ‘judging’ or ‘labeling’ women even though one cannot really know what is behind a facade.”

Berlin, 2012, self portrait: “I came to Berlin for two kinds of passion, the kind one feels for a city and for a man. This was taken during my stay in his apartment but he was not home. It was really erotic to be surrounded by his things without him being there with me. So I played around with the idea of my fantasies of him being there with me.”

In 2009, at the insistence of her cousin, Eylül started a Flickr account and uploaded some photos. It was a risky move, putting her name to her art. “I didn’t think that anyone would ever discover my work, so I didn’t care,” she says. “But then my father said one day, ‘I googled your name and you’re going to delete those photos.’ My mother always said, ‘I appreciate and love you for who you are, and you need to learn this.’ But my Dad was always, ‘Oh, what will our neighbours say?’ For him, it was about honour. He said, ‘I can’t even look at these photos — I’ll be living in sin!’ Those were crazy days, and sometimes I felt that art wasn’t enough to save me. We had a big fight, and he resisted coming to my first opening, but he loves me, so he came in the end.”

By 2012, Eylül’s art had gained a following in Turkey. Encouraged by established Istanbul photographers to follow her talent, she moved to Berlin to express herself further. “When I moved here and was able to see men holding hands with other men, people who were free, I saw there was tolerance and people accepted each other,” she remembers fondly. “Being in [the infamous nightclub] Berghain for the first time — woah. That was amazing. I couldn’t believe there was this entirely naked man, just with shoes and socks on, and he was dancing. It was incredible,” Eylül smiles. “I stared at him out of curiosity. People said, ‘Eylül, you’re staring too much.’ I said, ‘I don’t care. This is wonderful! I’m going to stare at everyone today.’”

A further selection of Eylül’s photographic work

“Berlin is kind of a utopia for me,” she adds. “I thought, ‘You know what? I don’t care what happens, I’m going to do whatever it takes to stay.’ Well, I ended up falling in love with someone and marrying him — Martin, my husband — so it all just fell into place.” Things often work out that way for Eylül. “I’d known about FvF for four or five years, and one day I thought, ‘I will be on that some day.’ I just felt it — and look where we are now. I used to sit in a cafe under the gallery in which I held my first exhibition too, and thought, ‘I will be in this gallery one day,’ and it really happened,” she laughs. And so it went with love.

“But one thing I realised when I moved here was that maybe everyone is bisexual by nature. We just have a tendency for one sex or the other — we’re 70% interested in women, 30% interested in men, for instance. For me, it’s not even about that; it’s about people. About who you meet, and who you fall in love with. To be honest, I don’t care if they have a vagina or a penis. It’s about the person. I don’t fall in love with their gender; I fall in love with the person. I happen to fall in love with more men than women in my life, but I see it as a possibility now, which wasn’t even a reality for me ten years ago in Turkey.”

Her experiences in Berlin and time spent abroad have given Eylül a new perspective on gender in Turkey. “My Mum is a traveller. She and I travelled through Europe when I was young. Every time I went back to Turkey I thought, ‘Fuck… people can actually be free! It’s not that impossible.’ It gave me hope. When you’re in this bubble, you think life is only one way. In Turkey, you think all girls have the same problems.” Issues that straight men in Turkey are often unaffected by. They’re free to dress as they please or flaunt their sexuality, Eylül notes. “There’s a Turkish chocolate brand that uses hunks in their advertising: really well built, really hot guys. They’re topless with chocolate dripping everywhere — women in Turkey love that chocolate!”

The same advert, featuring women, would be inconceivable, so Eylül appreciates the sexualized billboards that are common in Europe. “I know it sounds horrible, but I don’t have anything against the objectification of women. Everything has been objectified: men, women, children, even animals. Everything we have turns into something we can consume. It’s just the reality of our lives. ‘Oh, stop it,’ people say, but then we should also never take selfies or make any art or any photos. I fight for the rights of women to be treated well; if someone chooses to be objectified, it’s her decision. If a model wants to have her boobs out on a poster, I don’t care; it’s her life.”

“Everything has been objectified: men, women, children, even animals. Everything we have turns into something we can consume.”

“It sounds contradictory I guess, but the fact that women can be objectified like that, gives them the right to be how they want. I love that there are boobs and arses everywhere; it frees women, in an ironic way. If you act as if women are something to be protected or hidden from the world, then it gives men the right to control them,” Eylül says. “Women can do whatever they want. If they want to wear a headscarf it’s none of my business. But the problem in Turkey is that most women are forced to wear it by their fathers, mothers, brothers etc. I’m not against the hijab if it’s a girl’s own decision. I respect that, but she needs to respect my decision to wear whatever I want too.”

This sense of mutual respect manifests itself in unusual ways. “We have transexuals and obviously gay men in Turkey. If they are famous, Turkish society loves them. If they are accepted, it’s because they’ve proved something: they’re successful, they’re famous,” Eylül says. In a way, it applies to her too. “Now that I’m known, people respect me. I’m accepted because my art is not just something I do for a hobby. They think, ‘She has a gallery. Woah!’ I have relatives that used to say, ‘It’s really embarrassing that you have these pictures,’ and now they’re telling me how nice it is that they can come to my opening,” Eylül says, with rolled eyes. But perhaps Eylül Aslan’s work has been accepted for a more powerful reason. Her images convey a simple but necessary message: “Our bodies alone have no significance. It’s people who give them meaning. In the end… it’s only skin.”

Thank you, Eylül — your work is truly inspiring. Keep sharing your art and challenging perspectives. Find out more about Eylül’s work on her website or follow her on facebook.

Meet more incredible photographers of FvF, or read about creatives in Berlin and Istanbul.

Text:Jack Mahoney

Photography:Robert Rieger