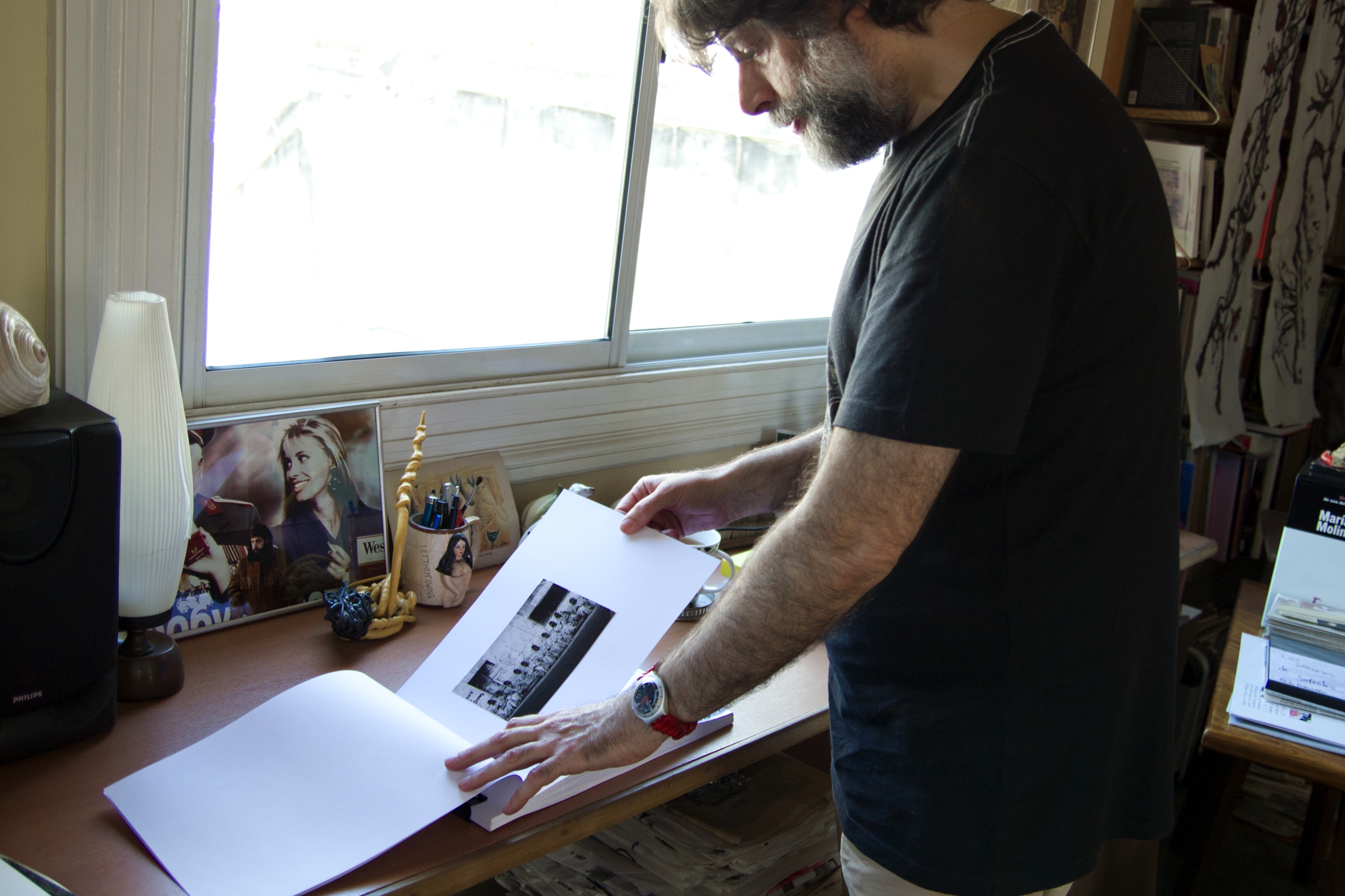

Perched on a sofa with his dog Luna sitting on his lap, Aldo Paparella tells us about his various passions and occupations, which have become almost completely intertwined over time. Besides his work as a filmmaker and a photographer, he is the director of one of Argentina’s oldest film schools, Cievyc, and editor of a book series featuring essays on New Argentine Cinema. For five years he co-edited a film magazine, the remnants of which are piled high in his cellar in the form of thousands of back issues that coexist with giant paper-mâché gargoyles from the set of his last movie.

His studio, located on the top floor, appears like a blurry snapshot of his mind: filled to the brim with books, movies, posters and paintings. Included in this collection are self-created paintings produced using traditional Korean techniques, a hobby Aldo started seven years ago following his passion for Asian art and culture.

Aldo’s stories about his career choices mingle with snippets of personal and political history, that make sense of the plethora of colorful memorabilia scattered around the house. Roman amphoras brought back from Italy by his father, and an array of family heirlooms display traces of his Italian roots, while the multitude of works of art spread throughout the apartment speak of his upbringing surrounded by the great Argentinean artists of the 60s.

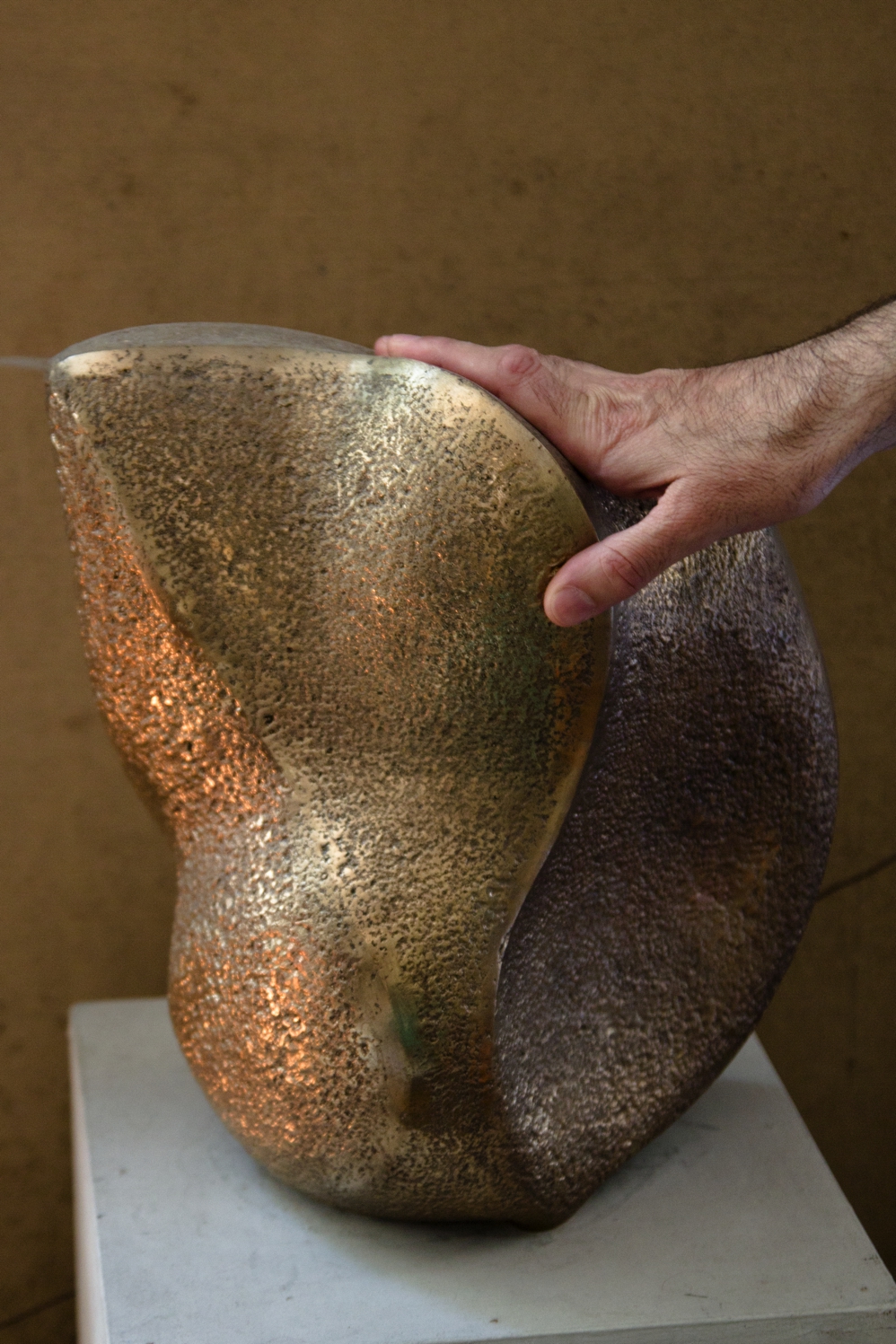

Aldo, the decision to dedicate yourself to artistic creation seems to be a natural consequence of your childhood environment – your father, whose name you inherited, has become an acclaimed sculptor. In what way did this circumstance shape the first stage of your life?

My childhood was a bit unusual. My father was a painter and a sculptor – there are some pieces by him here – and in general he was very different and bohemian. My mother was the same, she was an architect. Both of them were very special and lived for their work. All of this was quite normal for me, but when a friend would come to my house, he would look at everything as if he was in a different world. Our house was filled with strange objects, some of them still in the process of being made. I always say that I grew up surrounded by the great artists from the 60s, because all of them were my father’s friends. People like Libero Badii, Enio Iommi, Alberto Heredia or Raúl Alonso were always at our house.

Why did you choose the world of cinema if you had all these other options?

During my childhood, we lived for some time in my father’s hometown in Italy, a medieval village called Minturno. There was a cinema at the town’s entrance, and every weekend my grandmother would give me 100 lire to go see a film. During that time, ‘Peplum’ films – a genre of Italian films also known as ‘Sword and Sandal’ – were quite fashionable. These were movies of Roman gladiators and similar heros. While seeing one of these films I decided to dedicate myself to the cinema. I was eight years old.

Your development as a filmmaker occurred during a very critical political era – at the very beginning of the Argentinian military dictatorship. Did this have an effect on your professional development in some way?

I attended film school from 1971 to 1976, so the end of my studies coincided with the beginning of the dictatorship. It was very complicated and difficult to study cinema during that time. As a matter of fact, only one of my films survived, the other ones were all destroyed. On one hand this had the material effect of destroying what I had created. But on the other hand, it carried along a very profound consequence, one that lasted for years. I spent a long period of inactivity after the dictatorship. The repressive system had turned me silent – I remained mute for many years. Stepping out of this paralysis was very difficult for me.

Immediately after finishing university you decided to teach. Why did you choose this path? What made you open your own school?

I partially decided to do so because my own experience at school had been very bad. At the institute where I studied, under dictatorship the education was not the best. So as a consequence I decided to create a school where I would have wanted to study. But I didn’t open the school until 15 years after having finished my studies. I began teaching at the University of Buenos Aires, after that I taught at another film school and only then did I open my own one.

You have just finished production of a new film, Olvídame. What part of directing a feature film do you enjoy the most?

I very much like scriptwriting and editing. My last film was very complicated, it involved many locations, actors, technicians, and very little money. That implies great effort. It wasn’t really possible to enjoy the shooting, especially since I also produced the film. Having to juggle two tasks really overwhelmed me. I actually lost five kilos during filming, which took seven weeks. It felt like some sort of expedition.

Your studio is full of canvases, brushes, and objects related to traditional Korean painting. How does one start such a particular hobby?

It all began about seven years ago. In Buenos Aires there is a Korean neighborhood, located in Flores. I would often go there to buy food. One day, when I was strolling through the neighborhood, I looked through a window and saw people painting. As the son of a painter, I was very interested. I entered and noticed that there were students taking a class. I asked what it was about, and soon after I started. It was very funny because everybody was Korean and none of them spoke Spanish, not even my professor. She would only say, “Aldo, bad! Bad!” while hitting me on the back. She was a big Korean woman.

Let’s talk about your current home, the place where you live and work. What do you love about it and what makes it special?

It is a very old house and was constructed in 1900. We saw about a hundred houses before buying this one. What I liked most about it was the way the sun hit the building. Its natural lighting has a beautiful scenic character to it, with a very interesting volume. When we bought it, the living room consisted of three rooms, and we turned it into one open space. We conserved the large stained glass window, which was made in a forge. The floors are also original. We just lifted them and turned them around.

The structure of the house is typical for Buenos Aires, its style is called ‘Casa Chorizo’ or ‘sausage house’. The ‘Casas Chorizo’ are a copy of Pompeian houses, only divided in half. The design was brought over by Italian building officials and construction workers. It typically has two joined courtyards, one being more public while the other is more private, onto which all rooms open out onto. Duplicating this design you would get a Pompeian house.

The original owner of this house used to provide ice for the Abasto market. This very market, which is now a shopping centre, used to be a central wholesale market. It gathered a large variety of vegetables, fruit, meat, and poultry which were distributed all over the city. This market naturally needed a big supply of ice. The owner of the house was the only one who had a car in this neighborhood. The house seemed to be quite sophisticated for the time. When we renovated the house we found remains of gas lighting, copper cables, and a special type of chimney where tablets were burned in order to produce gas. It was a very advanced house for its time, there were only few houses who had gas illumination.

How did you discover all of this?

A taxi driver I had hailed for a ride told me. He was a bit older than me and it turned out that he used to live in front of this house as a little boy and knew the owner. During our ride he also told me that the house’s doors were never closed. He would arrive, take the stairs, and go all the way to the front door into the middle of the stairs. If you pay attention you’ll notice a caller there. That goes along with an idea of hospitality, the fact of being able to enter a house without needing to wait outside. I think this is very Latin – this idea that guests need to be welcomed inside the house.

In regards to your urban explorer side – both looking for film locations as well as for subjects to photograph – I would like to know what parts of Buenos Aires interest you most. Where do you find material for your photo books?

I know the city like the back of my hand, which is why I have lost the sense of wonder with Buenos Aires. I don’t really see it anymore, I navigate the city almost blindly. Sometimes I try to do some sort of exercise in estrangement and try to see the city with new eyes, as if I hadn’t been born here.

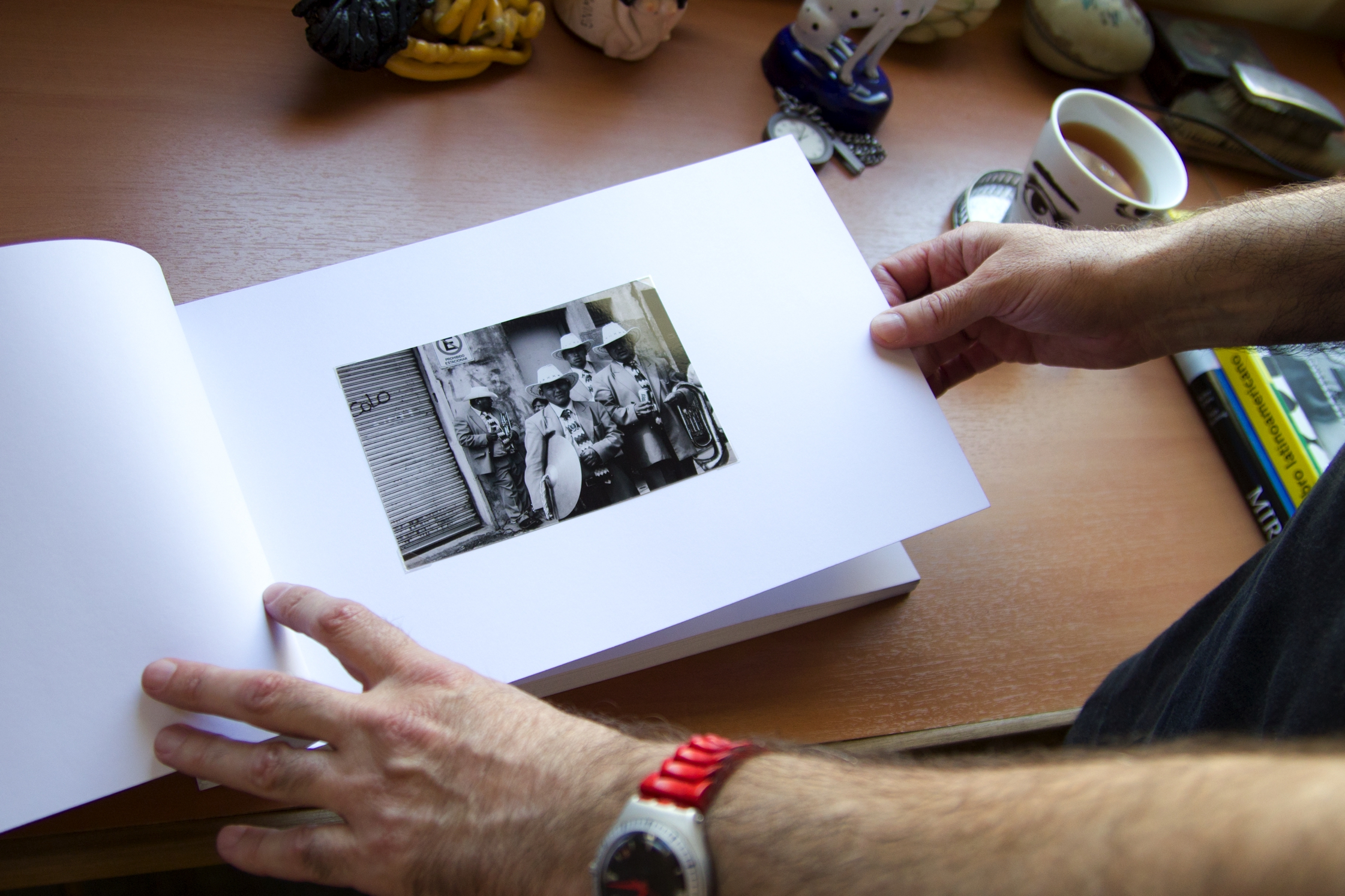

Only recently I finished a book about the annual Virgin of Copacabana celebration. It is a festival that just turned 40 and is held next to the San Lorenzo stadium, close to a slum called Villa 114. I photographed this quite dangerous place during the celebration for eight years. The event is organized by the Bolivian community, and there are very few tourists and few native Argentinians. People parade in typical dress accompanied by music and there is a lot of dancing and drinking. The music is so impressive, it is overwhelming. You enter a very particular world and vibration. This is an unknown aspect of Buenos Aires that I like because it leaves me speechless. I had never seen it before.

I used to go on a lot of photowalks, which I don’t do as much anymore. I went through a period where I took a lot of street photographs, but now I dedicate myself more to conceptual photography – the result of a photo production. It is a process that comes closer to constructing a film set.

A couple of years ago you published Futuramic, a book containing photographs of old cars, specifically from the 50s. Where did you get the subjects from? And why are you especially interested in this period of time?

If I could, I would live forever as if I was between the age of eight and nine years old. That was the happiest moment of my life and I think the book references that. I photographed the objects that coexisted with me during that time. The book is dedicated to my parents. Ultimately, I think that these pictures represent a tombstone of this entire period; of my childhood. That is actually how I see these cars, like mobile tombstones.

Why do you focus on cars? If it is about capturing remains of a that specific time, you could also have photographed buildings, furniture or any other object.

Cars are very important to a boy. My parents used to take me to the riverbank of Buenos Aires in one of those cars, driving along the Río de la Plata. They would take me there to see the seaplanes take off on their route to Montevideo. Unfortunately they disappeared from Buenos Aires. I was never able to fly in a seaplane, which is one of my biggest wishes.

Now that you mention Uruguay – you gathered a lot of material for your book there, didn’t you?

Yes, because old cars were maintained there and used every day. It is part of the place’s idiosyncrasy. In Cuba, where I also took many pictures, it is done out of necessity. In Uruguay, I think it happens as a form of nostalgia, people like to hold on to old things. I identify with them a lot. In general, I identify myself with people who love objects.

Does that mean that you also tend to treasure objects?

In reality I am not a collector, I am only interested in some objects. To me, photography has a gathering function. For instance, if I take a series of pictures of cars, it has something to do with collecting. I prefer to collect images rather than objects.

What other image collections do you possess, besides old cars?

I collect buildings. During trips, I take photos of people’s homes, I like to see how and where human beings live. With the material I gathered along the way I published a book called ‘“Aquí viven” (They Live Here). The book starts at Easter Island, in some caves where the natives lived, and goes all the way to the Flatiron Building in New York.

It includes everything, from the homes of the indigenous people in the South of Argentina, the palafitos (stilt houses built in the water) of Isla del Castro, the Cavanagh building, homes along the Po, the houses in Brasilia, which is an invented city… it is infinite. Perhaps we don’t pay too much attention to it, but the climate and the place where people live really determine the character of their homes.

Thank you very much for your time and welcoming us into home for this interview, Aldo! For more information visit his website here.

Photography: Gerardo Azar

Interview & Text: Julia Keller