Attaching meaning to bricks and mortar is something human beings like to do. We point out where we were born and where we used to go to school. It’s a job center now. We do it to clubs, too. That’s where the Hacienda used to be. This spot used to be home to The Four Aces club. Over time, clubs gain legendary status, and for good reason. Clubs give us some of the most vital experiences of our lives. You can make lifelong friends over a love of music. Plus, if you’ve never been into sport, it can be the first time you’ve really sweated. Clubs help us to identify who we are and who we would like to be. They are the unsuitable guardians that bridge the gap between our teenage years and adulthood. If we’re honest, though, are four damp walls deserved of such high esteem? If people are the sum of their experiences then surely we can think of someone better to thank than sticky floors and clogged up toilets for making us who we are today.

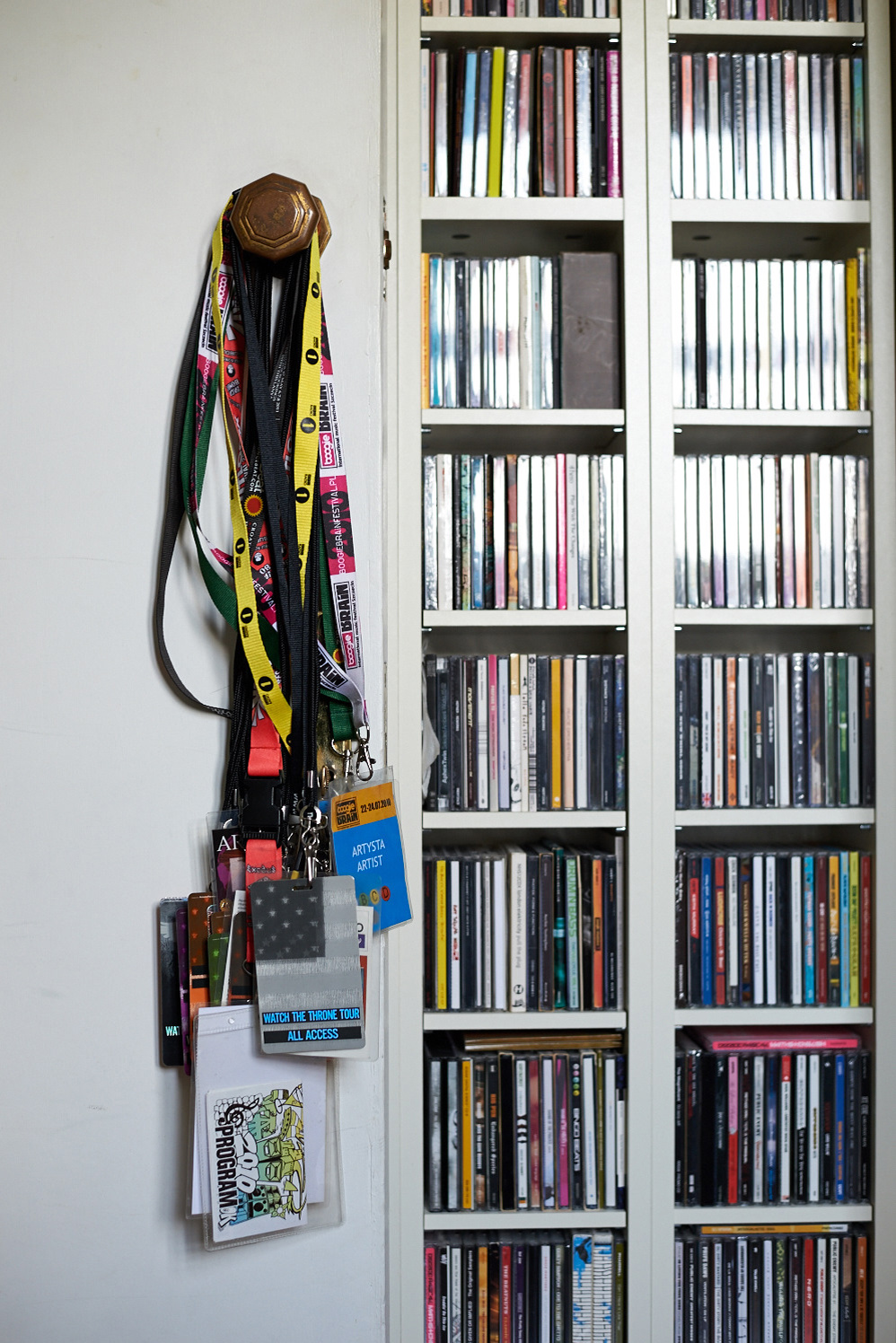

Clubs are the body but it’s the humble club nights that are the soul. When it boils down to it, a club is a commercial venture. It can crumble, it can change hands, it can fall victim to violence and crime, it can be shut down. Club nights are like us. They grow, adapt and move on. For Benji B, his love of music was passed onto him by his parents and explored through time spent in dark spaces with cranking sound systems during his youth. Experiencing the music scene in the 90s inspired him to found his own, now well recognized night, Deviation. We met with Benji in his apartment and studio in London to discuss his DJ career and subsequent role as a BBC Radio 1 DJ while discussing the notion of the ‘underground’ in dance music.

This portrait is part of a collaboration with Sennheiser’s Blue Stage Magazine, that explores people, who create unique sound and music, in their living and working environments.

We’ve arrived at Benji’s flat at an inappropriate time. His girlfriend is rushing around, getting ready to leave for the airport, and a man from John Lewis has just arrived to deliver a washing machine. He can’t get it up the stairs. “It’s hardly MTV Cribs,” Benji says. “I haven’t even ironed my shirt. At least you’re getting the real life experience.” As well as running Deviation, Benji has been DJing for nearly 20 years and has a longstanding show on Radio 1. “I’ve travelled the world with work but still live within the same two square miles of where I grew up.” Does he plan on staying here? “That’s a good question, I don’t know the answer to that.” “I do,” says his girlfriend. “Sometimes I think a change would be nice,” Beni continues. “I flirted with the idea of moving to New York in my 20s but I’ve realized that I’m a through and through Londoner and there’s no point pretending any other way. London’s my home.”

Benji’s parents both went to art college and his dad, a musician, has had a big influence on his career. “Those speakers are actually the speakers I grew up with. They were at my dad’s house. I got them reconditioned and the guy told me they’re now worth £10,000 or something ridiculous. My dad’s really into music, they both are. They were from the hippy era so naturally they loved Joni Mitchell, plus a bit of jazz and Tamla Motown. The first time I really got to see what a sound system was like was with my dad, he took me to Notting Hill Carnival when I was about seven or eight. It was really loud. I remember thinking it was mind-blowing that someone was playing a record that loud. It was a real moment for me. That and going to see Public Enemy at Brixton Academy. I remember staring up at Terminator X and thinking, wow, I’d love to do that.”

Having been a Radio 1 DJ for the past four years, Benji is not what you could call underground anymore. But then, like his predecessors such as Gilles Peterson, Mary Anne Hobbs and John Peel, he’s trusted by the BBC to play what he wants. “I’m not sure what it means to be underground anymore. I’ve shed my prejudices about commercialness and accessibility. It’s not about staying underground but about being committed to making good music and using your powers responsibly. I remember seeing Masters at Work at Ministry of Sound once, when the club was at the peak of its fluffy bra stage. Right in the middle of the set, Kenny Dope dropped a twelve minute Fela Kuti song. Jesus, I thought to myself, that’s DJ power.”

London in the late 90s was an exciting place for music. It was a playground for DJs, producers and MCs, whose reputations grew considerably thanks to pirate radio stations like Kool FM. “Most kids my age weren’t into the same music as me when I was growing up so I searched beyond that and found myself in clubland. There were always events on nearby. There was Jah Shaka at The Rocket and the Complex in Islington. There were always things on at the Dome in Tufnell Park. That’s actually where I had my first gig. It was the era of Super Sharp Shooter so I probably played a lot of jungle. Right next to the Astoria there’s a skinny little street, I’ve forgotten the name of it, with a little club called the Mars Bar. I used to go and see Fabio and Bukem there every Thursday night and be at “That’s How It Is” at Bar Rumba on a Monday. Then there was Metalheadz at The Blue Note on a Sunday. I haven’t experienced that intensity in clubbing before or since. Firstly, the sense of community, secondly that they would put their own sound system in, and thirdly that it was on a Sunday – and finished at midnight. These nights were taken very seriously and it was exciting. It wasn’t so much about getting high or wasted or meeting girls, it was about music.”

A meeting with one of his favorite DJs marked the start of his own career. “I walked up to Gilles Peterson in a club and said something I’d only have the balls to say when I was 15, which was: ‘I really like your show on Kiss FM but I can make it much better.’” After producing and contributing to Gilles’ shows at Kiss and the BBC, Benji went on to on have his own show on sister station BBC 1Xtra when it launched in 2002. His new music show moved over to Radio 1 in 2010. “I love going into the BBC, it’s a privilege. I can play whatever I want on the radio, that’s the greatest thing about what I do. With that opportunity, I love to celebrate and represent new music. I’ve always wanted to support the kid down the road that’s making really interesting beats just as much as the superstar artist – it’s the music itself that is the driving force for me.”

Starting out in 2007 at the 200-capacity Gramaphone, Benji’s highly respected club night Deviation was initially a labor of love, one that didn’t grant an immediate return. “I ran Gramaphone at a loss, it cost me hundreds each month, but I wanted to do something for the 18-year-old me. Someone had to take the baton on.” Before long, the night became so successful that it moved to XOYO last year, close to the north London borough where Benji grew up and still lives. Over the past few years, Deviation has hosted Madlib, Omar-S, Floating Points, Martyn and Kode 9 amongst many other special names, with Todd Edwards and young Detroiter on the rise, Jay Daniel playing the most recent session.

Benji took the decision to put Deviation on a Wednesday night in a part of Spitalfields which was, at that time, forgettable at best. It did nothing to deter the music obsessives who were willing to put themselves out to see their favorite selectors. “We’d have Theo Parrish and Moodymann and Kenny Dope playing, but alongside new names. We were the first people to book Flying Lotus in the UK and Hudson Mohawke, too, I think. We wanted Deviation to be somewhere that you would have a big name playing after the dude from round the corner who made beats. Yeah, they might have a different musical pulse, but they have the same belief and integrity.” As he’d hoped, having established what the night was about, punters were open to unexpected bookings. “If you build the right audience, people are open to that. I remember we once put on this kid from Austria called Dorian Concept. He turned up with one of those click on Playmobile haircuts and took out his little microKORG, it had a few keys missing. At that time the crowd didn’t suffer fools. Even Judah looked at me and was like, “Are you sure about this?” Then of course he slayed it, completely blew everyone’s heads off.”

By Deviation’s fourth year, it had become so successful, it had become unpleasant. There’s nothing like a few petty scuffles and door politics to turn what used to be fun into a bit of a chore. Still, Benji must have realized he’d lose some of the intimacy and chin-scratchers by moving to Friday nights at new super club XOYO. “It was a huge decision for me because I was worried about the sort of crowd that it might attract but I think it’s important to let things evolve. And I still get people coming up to me asking for an obscure track that I’ve played on my show the week before. Sometimes I might see the odd face and think, ‘Are you in the right place?’ – the sort of shiny shirt and miniskirt crew – but the dance music culture that I come from is based on complete non-exclusivity. Every race, sexuality, political persuasion is shed when you walk on that dance floor.

With these romantic notions, even Benji isn’t immune to the pull of a purer time. “1981, Lower East Side, New York. ESG playing upstairs, Bambaataa playing next door, Red Alert playing downstairs. It is easy to mythologize about times in club world – when I tell some kids what nights I went to they look at me as if I was at Woodstock – but every era has its moments. But in this era in New York, everything was just popping. A band like Talking Heads or Tom Tom Club could not have emerged from any other time. Culturally, everything was happening. It contributed so much to underground culture of the last thirty years and to where we are now, it’s insane. If someone gave me a time machine and said I could go to any time in history, I’d still probably go there.”

Benji’s never released his own music, but now that he’s set up his studio, has it become a consideration? “Yeah, it’s something I should have done fifteen years ago.” It’s never too late. “No, it’s not. I’d quite like to create something tangible. I’m best known for being on the radio and for club nights, but you’re only as good as your last performance. It interests me to think what I’d have if those things stopped. I’m really happy with what I’ve achieved but I can’t bottle it. As a legacy, what am I leaving? Ultimately, it’s just a night and only the people that were there will remember it.” It’s an understandable concern, but one that seems redundant. Having heard Benji enthuse about the influence that Kiss FM and Speed at Mars Bar had on him as a teen, there’ll no doubt be another kid among the shiny shirts ready to take the baton on into London’s club future.

Photography: Sebastian Boettcher

Interview & Text: Amelia Phillips