Tucked away in a quiet spot of the Achrafieh district in Beirut, Caroline Tabet’s apartment is a spacious and ordered living-slash-workspace. The photographer often works alone, in the living room, where the tell-tale DJ decks indicate the presence of her husband Jawad Nawfal, a musician and sound designer, and Tabet’s own DJing habit.

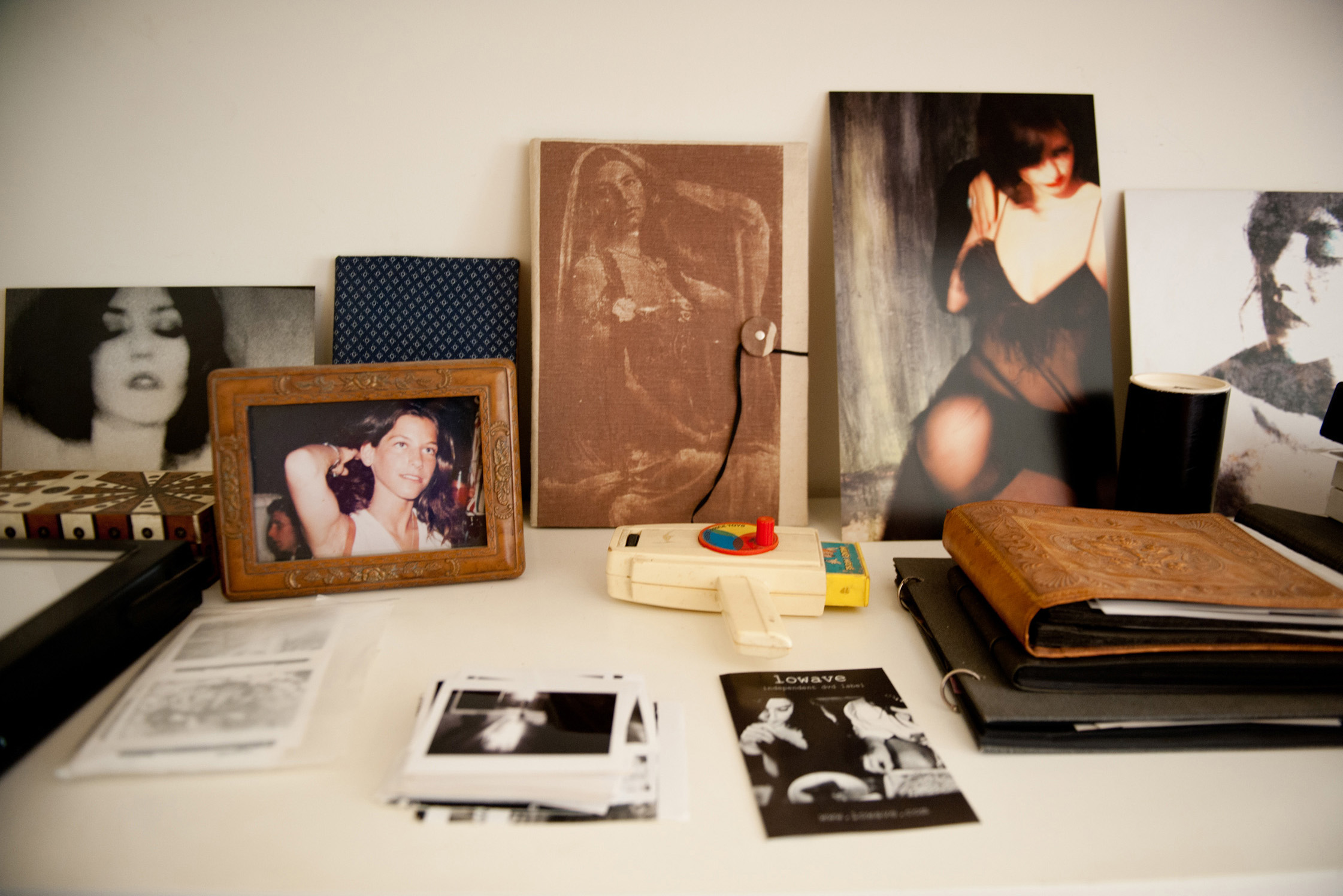

Like many Lebanese artists who found themselves in France during the Lebanese Civil War, Tabet’s style and mannerisms have a Parisian influence – the photographer wears her jeans and Converse with the grace of a ballerina as she asks us how we take our coffee (“Nescafe or espresso?” is a routine question in Beirut). Paris also provided Tabet with her first taste of professional photography, where she assisted shoots for fashion magazines and advertising campaigns. Returning to Beirut in the early 90s, her subsequent work has dug deeper. Her solo work and collaborations with Joanna Andraos as “Engram” revolve around, although not exclusively, stark architectural landscapes, the human body and nudity…often exploring the sensitive interplay between all three.

This Portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who present a special curation of our pictures on their site. Have a look here!

How long have you lived in this apartment for?

Since 2007. I lived in different areas of Beirut before that.

What attracted you to this neighbourhood? It’s a quiet part of the city.

Yes, it’s a calm neighbourhood in a residential part of town. There are a few shops and a school, so there’s a lot of movement during the day. But at weekends it’s very calm. We’re on a hill so it’s also one of the highest parts of Beirut. There’s a lot of wind and it’s quite luminous.

Are most of the artworks on the wall your own?

Yes. Some are my own photographs. Some of them are part of the project I have with another photographer, Joanna Andraos. We work under the name Engram.

Can you explain the meaning behind the name Engram?

It’s a scientific name, a biological name. It’s a memorial trace that prints what you see into your memory.

How did the collaboration start?

We started in 2003. I’d met Joanna briefly before through friends, in Beirut and Paris. We met again on a photography set in 2002, and it really clicked. Usually photography is lonely work but, I don’t know how or why, it felt natural to work together. Our first project was an installation called Numbers. It’s a series we did in very public spaces. We asked a person, usually a girl, to sit or stand in a public place, like a train, a bus station or a stairway, where people are passing through. We wanted to work on the relation of humans in the urban fabric. We started in Beirut and then travelled to Cairo and Paris. We want to show the similarities between different cities in the world.

Your photographs vary from architectural cityscapes to nudes.

Can you pinpoint any overriding themes that connect your work?

It’s difficult to talk about themes. I’m interested in the relationship between humans, the body and the interaction between these contexts in architectural space. I like places that still feel raw or abandoned. The place becomes like a skeleton and the body can express itself into this skeleton. Photography for me is also a work on light – natural light, studio light or whatever. It’s like a painter, it gives shapes to things.

After your career began in Paris, what made you decide to return to Lebanon?

I was born in Lebanon but during the war my parents moved to France. So I didn’t really know Lebanon. I wanted to discover the country and to live here. When the war finished I was in Paris, working as an assistant photographer on fashion sets, for advertisements, magazines.

Did you enjoy it?

Not really, actually. It was interesting to discover this side of photography, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do. When I came to Lebanon in 1993, there wasn’t a lot happening. There were hardly any projects and it was difficult as a photographer. I started to work with the Red Cross. Then I began working with an agency doing films – short movies, advertisements – and I discovered videos. I’m fond of images but I also like moving images a lot, so I got deeper into that. Then I returned to photography as a set photographer, I did my own personal projects, and slowly slowly I came back to it.

How did being in Lebanon at that time influence you as an artist?

A lot. I didn’t have the easy option like I did in France. Everything there was settled – you had agencies, you had everything you wanted to be able to work in photography. Beirut at that time was desolate. I was interested in getting lost in the streets and getting lost in this country of mine, with this very lonely feeling. There weren’t nearly as many restaurants or bars as there are now. I started to really work on the city, because it was the city that was so present. It really influenced my work.

An aggressive urbanisation is taking over the city now. How does that make you feel?

We can’t be nostalgic about Beirut. It’s becoming something that’s out of our hands. The anarchic urbanism of Beirut is really frightening and very sad. There is a part of the city’s soul that is living, but we also have to be able to work with this ugliness that’s rising around us. I realised recently that places I work with often disappear. I did a series in 2010 with a Lebanese dancer called Zeina Hanna. I took photos in a big concrete structure next to Tabarja beach, an unfinished hotel. This year the building came down. Even the concrete structures are disappearing.

Does that make it a more fertile environment for your work than a very structured city, like Paris?

Paris is interesting in other ways. I like to work in Paris. The laws are very uptight… there is not a lot of possibility for flexibility. You won’t see many changes. But in Lebanon you will always have surprises. You’ll walk in the same street and something would have changed. There’s something ephemeral in Beirut. And photography is an ability to capture something so ephemeral. They’re a mirror to each other.

You and your husband both work from home. Do you interfere with each other’s work?

We exchange a lot. We spend a lot of time at home. It’s a big space and we have our parts – I’m here and he’s in the studio. He’s produced music for my short movies and installations. He uses my photos for his album artwork. We have a common project together where we combine music and video, and we do live performances together. It’s a very nice exchange.

How did you meet?

We met a long time ago! In 2000. I was living in an old house with my friend Zeina. Jawad was a student and took one of the spare rooms… and that’s how we met [laughs]. It was 290 Lebanon Street. The house was eventually destroyed and we did a project on it.

How do you spend your free time together?

Jawad works most of the time. We share music. I DJ. We do a lot of music nights and parties together. Recently we went to Berlin, while Jawad was working there.

Did you like Berlin?

Yes I liked it very much. It’s the kind of city where you feel there’s space for everybody. It’s very easy-going and the people are simple and kind. Even though it’s a big city and it can be a cold at times. Music wise there’s a lot to do and the public is just great. I would love to go back. It has this ephemeral situation like Beirut. There are a lot of similarities between the cities: oppression, war, the division of the city. Some artists have done some really interesting work about the relationship between Beirut and Berlin.

Would you ever move?

We’re thinking of moving actually. We’re going to be very flexible between Berlin, Paris and Beirut so we might move into a smaller space.

What are your most treasured possessions in the apartment?

My negatives and slides! I had a bad experience with an apartment in Paris which burnt down and I lost everything. The negatives go back to 1991. Some of them are even in older. Then there’s the hard disk, which is also important, all the digital. And this camera. It’s a medium format camera called a Hasselblad, it’s Swedish. It’s like the Rolls Royce of cameras [laughs]. It’s almost unbreakable and you can trust them to work forever. I also have an ancient statue which was found underwater next to Tyre [South Lebanon]. It was a birthday present from my father in law. Everything is faded, it’s beautiful. I love it.

You have a great library. What have you been reading recently?

“L’exactitude des songs” by Denis Grozdanovitch. He’s a photographer and a writer. It means “The Preciseness of Daydreams”. It’s very simple photography, the photography of daily life.

Thank you Caroline for letting us explore your apartment and city! Learn more about Engram and Caroline’s work here.

Interview & Text: NJ Stallard

Photography: Tanya Traboulsi