At his home in Cologne, he likes to lie back on his living room carpet. He then stares up at the blue sky and feels a bit like he’s back living in L.A. again.

Daniel Hug is restless. Homeless. He’d be the first to suggest that of himself. The American with Swiss roots has moved at least seventeen times in his life, though exactly how many times he couldn’t say for sure. He grew up in Zurich. After his parents divorced, he moved to the United States with his mother. More moving around and studies in fine arts at the Art Institute of Chicago followed. He then entered the art trade and lived in Los Angeles. For eight years now, he’s lived in Cologne and worked as managing director of Art Cologne.

“Cologne wasn’t cool when I got here—everyone wanted to go to Berlin.”

Postwar architecture instead of palm trees and Rodeo Drive. Cologne coterie rather than cosmopolitan art flair. “Cologne wasn’t cool when I got here—everyone wanted to go to Berlin,” Hug recalls. Yet this ‘uncool’ city on the Rhine does enjoy a good location. Close to the Benelux countries and Paris. Not too far from London. And art in Cologne has history: “Starting in the ’60s, Cologne was the art capital of Germany. The Cologne-based art collectors Peter and Irene Ludwig were collecting Pop Art before the Americans themselves had even thought about it. Even today, the city has a very strong art scene. There are important and established galleries here. Cologne is a large city and at the same time intimate. You can build and maintain personal relationships and friendships within the industry and have more opportunities for exchange than anywhere else.”

“Few young gallery owners manage to reach the next level. The expiration date of a gallery is about five years nowadays, but of course there are exceptions.”

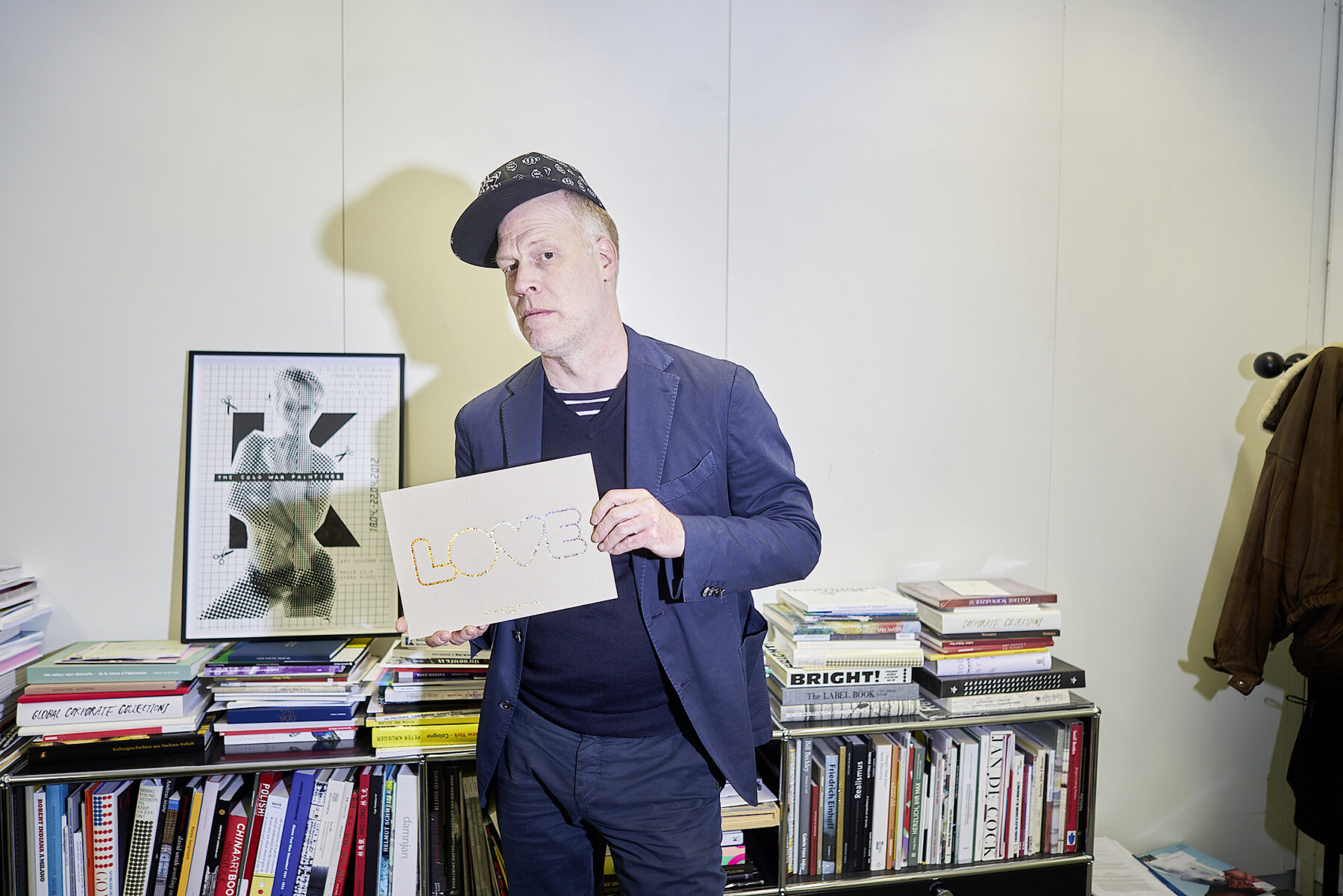

Daniel lives right in the center of Cologne. He takes the train to the other side of the Rhine to get to work at the Kölnmesse, Cologne’s trade show center. Over the last three months before the event, he’s spent most of his time in his office on the tenth floor. You can tell that there’s plenty of work going on here by the number of exhibition catalogs and art books piled up on one other.

He nearly makes it sound banal when he describes how he’s kept Art Cologne tipped for success for several years now, as if he were teaching his son to ride a bike. A piece of cake: “You have to bring in the international heavyweights to mingle with the exhibitors at the show. It’s like in high school. If the cool kids are doing something, the others will want in on it as well.”

Under his predecessor, Gérard Goodrow, the show was geared more towards quantity than quality, and featured almost 300 participants, but gradually lost importance. Renowned international exhibitors and collectors stayed away. As the new Managing Director, Daniel reduced the number of exhibitors to around 190 galleries. He introduced new, logical structures: small stalls at cheaper rents for emerging galleries and more space for established exhibitors. A bold new approach, for sure, albeit one without guarantee of crowded convention halls. But his enthusiastic eyes reveal the truth: He is an excellent networker. He manages to inspire people and bring them together. Today, Art Cologne has become indispensable as an art fair of international standing.

“You don’t necessarily have to understand a work of art, but it has to raise questions. I think that’s important. I like art that irritates me.”

“Critical thinking. You find creative ways to solve a problem. And don’t go by the book,” claims Daniel as he describes his own approach with a sly grin. He’s best at talking about art in English. When he speaks of what he has planned for the show, his eyes begin to light up. In the future, Daniel wants to use Art Cologne to better promote young galleries in particular. Called the ‘Neumarkt’ (new market), he’s adding a private area in which young exhibitors can present individually or as part of a group. He’s very aware of his responsibilities in the capricious business of art: “It’s like in the fashion world. As a supermodel, you have about five years. Then it’s over. Few young gallery owners manage to reach the next level. The expiration date of a gallery is about five years nowadays, a trade show has about 10–12 years before they start having difficulties. But of course there are exceptions.” Yet as the oldest art show in the world, Art Cologne has long left this limit far behind.

Since Daniel has been living in Germany, he has learned a lot about the way the German art market works: “In Germany, the middle class, in particular, collects art. In the States, it’s mainly the super-rich. There are perhaps three Germans who can afford a Jeff Koons at 20 million. Here it’s not so much about speculating. The Germans mainly buy what they like.”

When not in the office or on the road, the family man prefers to spend his time at home with his wife Natalia and his two-and-a-half-year-old son Nikolai. Natalia is a gallery owner, grew up in Riga and subsequently lived in Vancouver for many years. The fact that she speaks very little German is not a problem—the Cologne art scene is international enough to forgive her for it. In 2013, Natalia came to Cologne and opened her contemporary art gallery. Her self-titled gallery is a minimalist gem located in Cologne’s trendiest district, the Belgian Quarter.

“Cologne was the art capital of Germany in the 1960s. The Cologne-based art collectors Peter and Irene Ludwig were collecting pop art before the Americans themselves had even thought about it.”

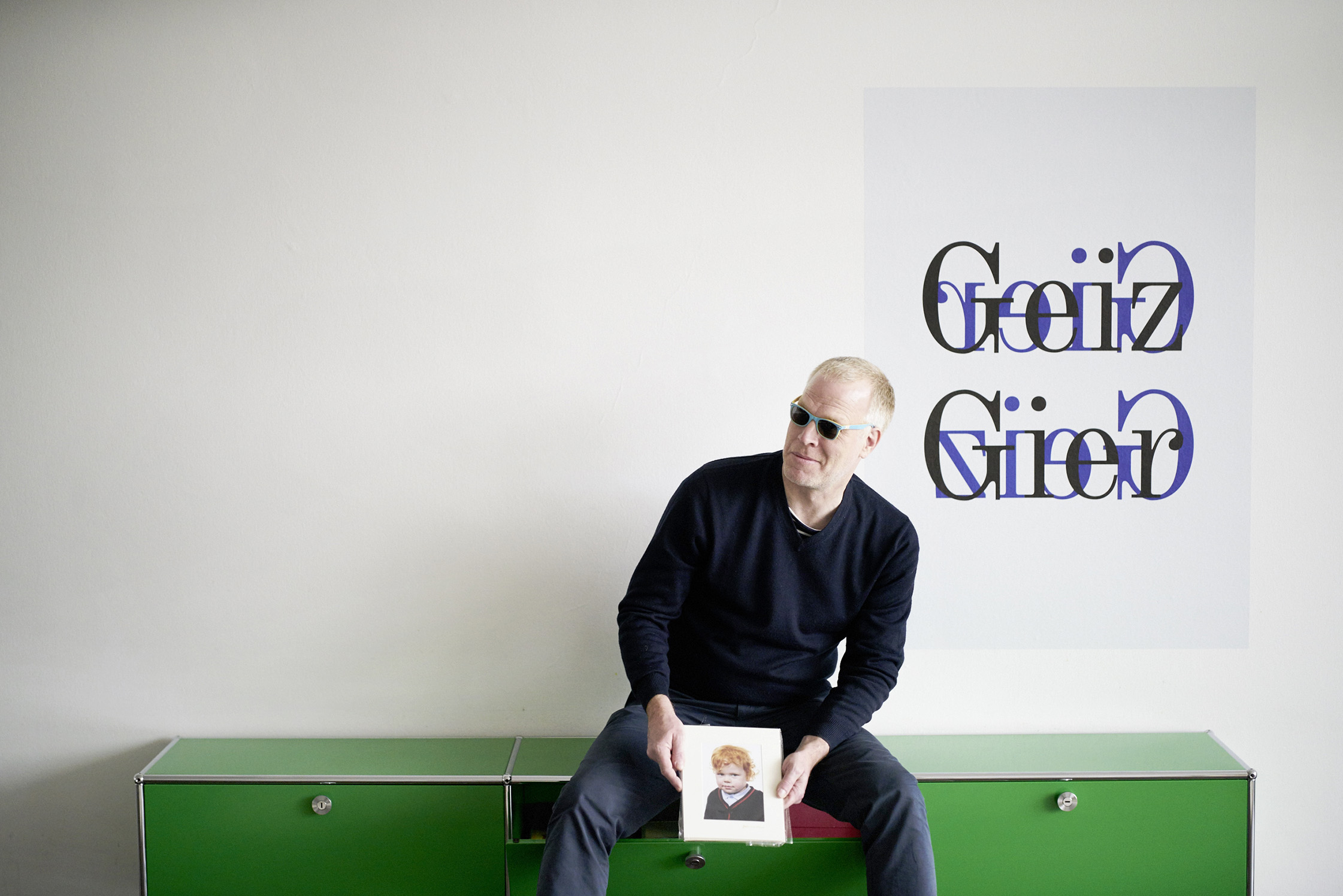

Just a few minutes’ walk from the gallery is the Hug family home. The simple modernist construction is not far from the historic Rudolfplatz, overlooking the Kölnischer Kunstverein,. Daniel only brings art into his own home when he has a special connection to it. There we find the two-and-a-half-meter tall “Standardpose” by Christopher Williams, which portrays a larger-than-life chicken against a light blue background. It was only possible to frame the enormous print directly in his home—the work of art would have otherwise hardly fit through the door. Daniel also owns a poster by Claudia Kugler, which typographically explores the antonyms of ‘stinginess’ and ‘greed’ in great serif letters. Hug runs his fingers over the cleanly applied edges of the artwork as he recalls that the artist herself came by to hang the work on the living room wall. In his opinion, good art doesn’t have to be expensive. His gut feeling decides what makes it onto his walls. “You don’t necessarily have to understand a work of art, but it has to raise questions. I think that’s important. I like art that irritates me.”

Aside from art, interior design is a special hobby for Daniel. He collects design classics by Marcel Breuer and Egon Eiermann. He prefers a functional style—modern. “As a child, I wanted to become a furniture designer. My father was an architect and told me: ‘We already have a perfect chair. It has four legs, a seat, and a backrest. What is it about that that you want to reinvent?’ That had an effect on me.”

For Christmas, Daniel’s wife Natalia gave him a storage space. He’s a collector. She’s a minimalist. This means both have to compromise: If it isn’t needed or hanging on the walls, it gets moved to storage. Consequently, Daniel is even more pleased by the bargains that do make it into the apartment. Next to the kitchen, in front of the oversized posters of Christopher Williams, you’ll find the tubular steel classic B27, a Marcel Breuer table from 1929. Daniel is visibly happy as he reveals: “Someone posted it on the internet with a very bad photo. I bought it for 101.95 Euros. What a crazy bargain!”

“Sometimes you have to look the truth in the eye and admit it to yourself: I’m not an artist.”

Daniel’s Marcel Breuer collection is his pride and joy. However, his eyes glow even brighter when he speaks of his son. Little Nikolai is growing up multilingual. He attends an English-language kindergarten and the nanny speaks German with him. Despite the long tradition of art within the Hug family, when the time comes, Nikolai will decide for himself what he wants to be. “Perhaps he’ll be a lawyer, perhaps an architect. Or a doctor. Doctor wouldn’t be bad. Then he could take care of me when I’m old,” Daniel says with a laugh.

And who knows? Perhaps Daniel will even grow old in Cologne. The eternal traveler. The homeless one. He could certainly imagine it in any case.

Thank you, Daniel, for sharing this wonderful insight into your apartment and family life. We wish you continued success with Art Cologne.

You can find more info on the art showhere.

This portrait was produced in association with USM and is part of “Personalities by USM” series. More information about Daniel’s interior design can be found here.

Photography: Michael Englert

Text:Sascha Abel

Translation: Brenton Withers