At one point Dirk Rumpff wanted to be a car mechanic but instead turned to the study of medicine. Regardless, the anaesthesiologist at Berlin Charité never lost his love of cars.

His longest relationship, he says, was with a Volvo Amazon. These days, there are three Maseratis in his garage, all classics. The hunt for replacement parts now takes up more of his time than collecting records, which is also a habit for Dirk: Back in 1999 he started the radio program OFFtrack, and since 2011, he’s organized CDR, an evening for young musicians at Berlin’s Prince Charles. In between he’s regularly produced music. So, perhaps it comes as no surprise that there’s not much time left for collecting furniture.

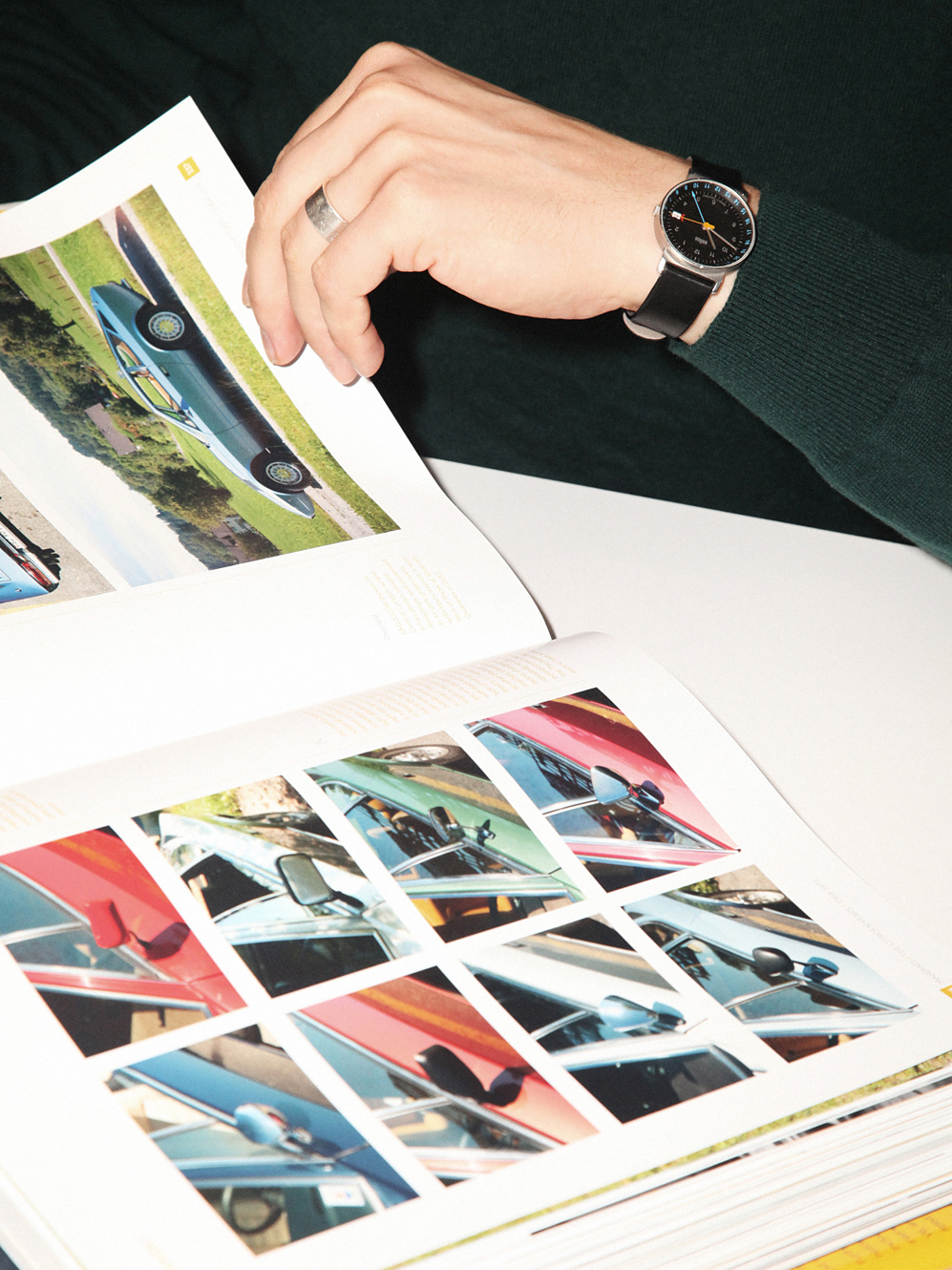

His appreciation for that which is timeless and requires a bit of knowhow to function at its glorious finest is apparent, as is his passion. From handmade car parts to a hand picked record collection, weighing in at over two and a half tons, this contemporary huntergatherer has carefully chosen his pursuits, cultivating a specialized knowledge in each.

-

You originally wanted to be a mechanic. Why did this goal turn into medical school?

I thought to myself, a car mechanic and surgeon really aren’t so different. To this day I am convinced that the way of thinking is very similar. When I started medicine, I wanted to be a surgeon. But then, through chance, I ended up in anaesthesiology, and I really liked it. I’m doing emergency medicine often and gladly. At the moment I’m specializing in intensive medicine. I find it really exciting.

-

You’ve always produced music, even brought out a few records. Why didn’t this become a career?

Although the music was always in parallel, I would have never had the option to pay my rent with it in the long term. I probably would have had to make more compromises, but I always wanted to do my own thing. It was good that I had medicine as a backup. After all, I’ve done the radio show OFFtrack for a long time and now we’re organizing CDR. That stands for Create, Define, Release and is an evening for emerging musicians at Prince Charles in Berlin. But it’s just a hobby.

-

How could one imagine it?

At CDR musicians have the chance to hear the music that they’re working on in the club. Additionally, we bring established artists in to share their experiences with musicians that aren’t so far along yet – to this point, for example, Peaches, Modeselektor, or Jazzanova. So things like, “I’ve fallen flat on my face, looking back what I would have done is…” or “When I’m in the studio and I don’t have any ideas, then I…” We try to find entertaining topics. Because I’m a big nerd and we also talk about equipment, but then we would only talk about compressor settings, and in the end only five people were still there.

-

How did the idea come about?

This concept has been around for over ten years in London, and Tony, who does it there, is a friend of mine. We modified it a bit for Berlin and went more in the direction of a workshop. We have the feeling that because of this a small community has built up around it. It’s fun.

-

Will your radio show continue at some point?

Yes, that’s the plan. Unfortunately, there’s no time, I can only do the show or CDR. I have the feeling that when in doubt, CDR offers more. In the meantime, everyone is doing a podcast.

-

What you played in the radio show was a pretty wide range of music. A lot of electronic music, but also indie or even folk music.

Hard trance and death metal weren’t played so often, but otherwise I tried to bring everything in. When I listen to the radio, I don’t want everything to have the same style. Or when you go out in Berlin, almost everything is some kind of techno or house. I like it when you go from one thing to the next and connect things that have no connection at first. But, as with everything, you have to dig pretty deep to find the pearls.

-

Why isn’t there more diversity in Berlin?

That’s the vicious circle that we talked about earlier: many DJs have to pay the rent with their work. And when you try something that backfires, maybe the next time you won’t be booked, therefore you prefer to play it safe. Sometimes it’s also good to deliver a few questions and not just answers. Magical moments mostly come about when one takes risks. I’d love to DJ again, I really miss it. But I have to take care of it, go out, produce things. I work a lot in the hospital on the weekends, then I’m happy if I can just sleep in sometimes. I’m almost like a pensioner raver. Actually, I totally embrace this culture of going out on a sunday afternoon.

-

You definitely have enough records to DJ…

Yes, that with the builtin wall to accommodate them was, unfortunately, not my idea but of my partner Atilano Gonzalez who I share the flat with. But they needed to go somewhere, and we didn’t want the Expedit from Ikea, so many DJs store their records on those. This was a factory floor and we had to build the walls ourselves anyways, so these wall depressions simply offered themselves up. However, this wasn’t as easy as it looks. All the vinyl weighs two and a half tons. So a structural engineer had to calculate if the floor would hold, and then we had to construct steel supports for underneath to hold this weight. And it’s still not enough space – a part of my collection is still in boxes.

-

And you have a fancy desk…

That’s really only there because we want to get rid of it and I don’t feel like putting it in the basement for today. We thought that for the photos we should put a price tag on it.

-

Did you ever consider converting your music collection to mp3’s?

How much emotional attachment can you have for an mp3 file? But I thought about it, this maybe hunting and gathering of records has now shifted to spare parts for the car.

-

And where does your passion for classic cars come from?

I was more or less raised with classic cars. My dad always took me with him to the Oldtimer Grand Prix in Nürburgring or to the Techno Classica in Essen. However, he never had a classic car. He thought they were beautiful, but never bought one. But I was there as an eight year old, taking pictures and got totally hooked. In the paddock at the Nürburgring, I could even run around between all the cars before the start – that was such a formative experience.

-

When did you get your first car?

I spent a year as an exchange student in the USA, there I bought an old Oldsmobile for a few months. Back home I was able to take over my uncle’s Volvo 164. It was built in 1971, dark green with red leather seats. Unfortunately, that was when the tax on cars without a catalytic converter was really expensive, and there was still no VIN number for vintage cars. I was still going to school, so I had to sell the car.

After graduation I worked for half a year in a mechanic’s shop, at Hartmann in Dortmund. To this day they restore Volvos. There was a Volvo Amazon from the sixties standing around. It was completely restored, perfect, but completely unaffordable. So I told the owners of the shop: “I want it, but I need time to get the money together.” For two years, every month I went to them and gave them the money I had earned in the meantime. I had the car for 17 years, my longest relationship.

-

Now it’s Maserati’s.

A Maserati was always a huge dream for me. On the one hand the history of the brand impressed me, and of course, they are timelessly beautiful cars. But also the technology was really innovative. There are a lot of feats of engineering in there.

-

Overall, they have a very delicate appearance.

Yes, the classic understatement from Maserati. Very nice cars, but not as loud as a Ferrari, which is striking at first glance. Gunter Sachs reportedly once said, “The playboy drives a Ferrari, the gentleman drives a Maserati.” The cars are typical Gran Turismos – less of a sports cars, more like a touring coupé.

-

But cars that take a lot from their owners.

With earlier Maserati’s almost everything was made by hand, in very small quantities. Back then these cars were almost prohibitively expensive. Today you notice it when you need spare parts. You have to be ready to suffer, because the repairs never stop, it goes on and on. And because of the handmade parts, they barely fit from one car to the next. But other than with Volvo, I’ve never really experienced a car where everything works.

This portrait is part of our series “Friends Of Cars” in collaboration with Spiegel Online. See the second part of the story on their website.

Read more interviews with interesting individuals in Berlin.

Photography: Anna Rose

Interview & Text: Kai Kolwitz