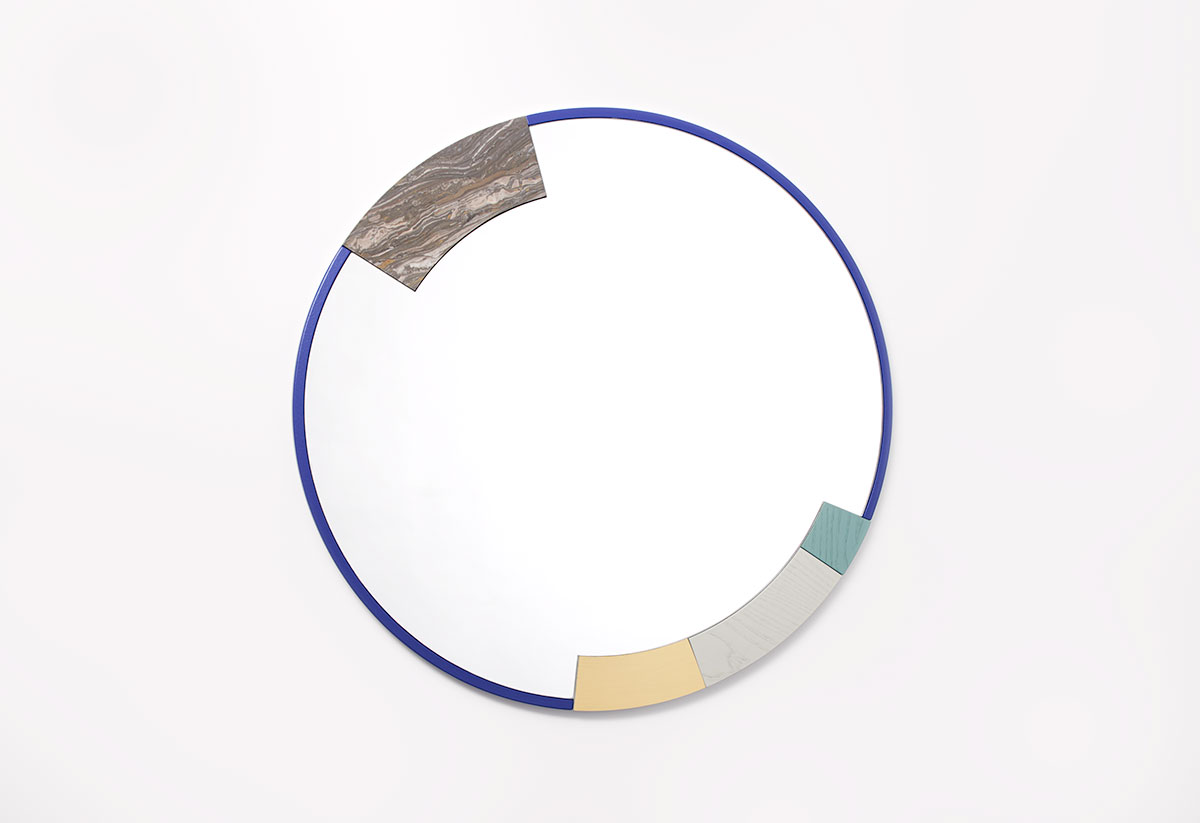

Zoë Mowat prefers to define her design aesthetic as a language rather than a style—when examining her body work, one is immediately fluent in her language of color, form and unlikely combinations of materials.

Based in Montreal and born to a sculptor mother and a psychiatrist father, Zoë grew up with a balance of the sciences and humanities at home—a balance that seems to have carried with her. The objects she designs have obvious functions, whether it’s to hang clothes, display jewelry or act as writing surfaces. While these objects have an inherent desire to be used, there’s always an element of play, with forms that invite wide ranges of use and reward creativity. We caught up with her in Eugene, where she’s teaching courses at the University of Oregon and spoke with her about this language she’s created.

This interview with Zoë is published in collaboration with OTHR, the forward-thinking Design brand that utilizes the latest in 3D Printing technology to create unique objects. Follow along as we profile their international roster of designers here.

Zoë at Studio Gorm, a friend’s workshop in Eugene

A temporary workplace while she teaches at the University of Oregon

“I trust my intuition as much as I trust the data and the research to make design decisions.”

Your mom was a sculptor and you were set to follow in her footsteps until you decided to pursue furniture design instead. Can you remember the situation that triggered that decision?

I think it was more of a creeping realization than a clear lightbulb moment, but I found my place in design at the intersection of sculpture and architecture. I was always engrossed in both, and I think it was when I recognized that similar principles like the manipulation of form and material, refined planning and the consideration of space, can be applied to a very direct, very human scale: furniture. The intimacy of this scale and the immediate feedback that is possible when interacting with objects—essentially the human element—is ultimately what I was drawn to.

“My mother taught me how to speak in three dimensions at a fairly young age.”

How did growing up with a mother that has an art related profession influence your design career?

Whether this was directly or indirectly (likely both), my mother taught me how to speak in three dimensions at a fairly young age. The exposure to her work, to the process of making, the consideration of scale, proportion, material, and philosophy was incredibly influential to me and my practice early on and it continues to be. Playing with these elements in my own work feels natural at this point, and I still rely on the sculptor in me throughout my design process. I trust my intuition as much as I trust the data and the research to make design decisions. My father is a psychiatrist, so I often joke about how my future in design was almost predetermined. Either way I have found a nice balance between their worlds: artful output concerned with the human experience.

How did you develop your personal style?

I tend to call this a language in lieu of a style, and it’s one that I’ve been exploring, refining, and developing through the years. I imagine that I was influenced by my mother and perhaps recognized and interpreted her own expression as a language or way of communicating. I think I initially identified the components (or vocabulary) while I was in design school and quite simply, I began to explore and manipulate the proportional relationships between material, color and form alongside design function and the human element that I referenced earlier. This expression isn’t necessarily formulaic and I rely on each new design brief to guide the process (and language) along.

You decided to open your own studio instead of joining an established firm, how was that experience?

In the beginning I was incredibly selective in the projects that I took on—I still am, however, I learned how to say no to the projects that weren’t suitable to the development of my studio (which was often challenging). Instead I sought out and chose to work with clients who really trusted my vision and approach, and from here I was able to develop new works that would help fund the development of future designs.

Looking back at starting your own company: What was the most difficult situation here and how did you solve it?

Managing all aspects of a business is a challenge, especially for a creative person who just wants ‘to make things.’ This was a steep learning curve for me at the start but I’ve grown more adept at balancing the less alluring parts of my day (administration) with what I prefer (designing).

You are also a teacher—that surely offers learning experiences in return, no?

I really enjoy teaching and I learn a lot from my students. It’s a very active process where you are watching the learning happen and evolve in real time. The ability to witness a student’s engagement, their questioning and thought process, can be incredibly refreshing. I’ve been encouraging the students to try and find and explore their own voice yet also be pragmatic and effective in their planning and output. My ultimate aim is to guide them to design honestly and thoughtfully.

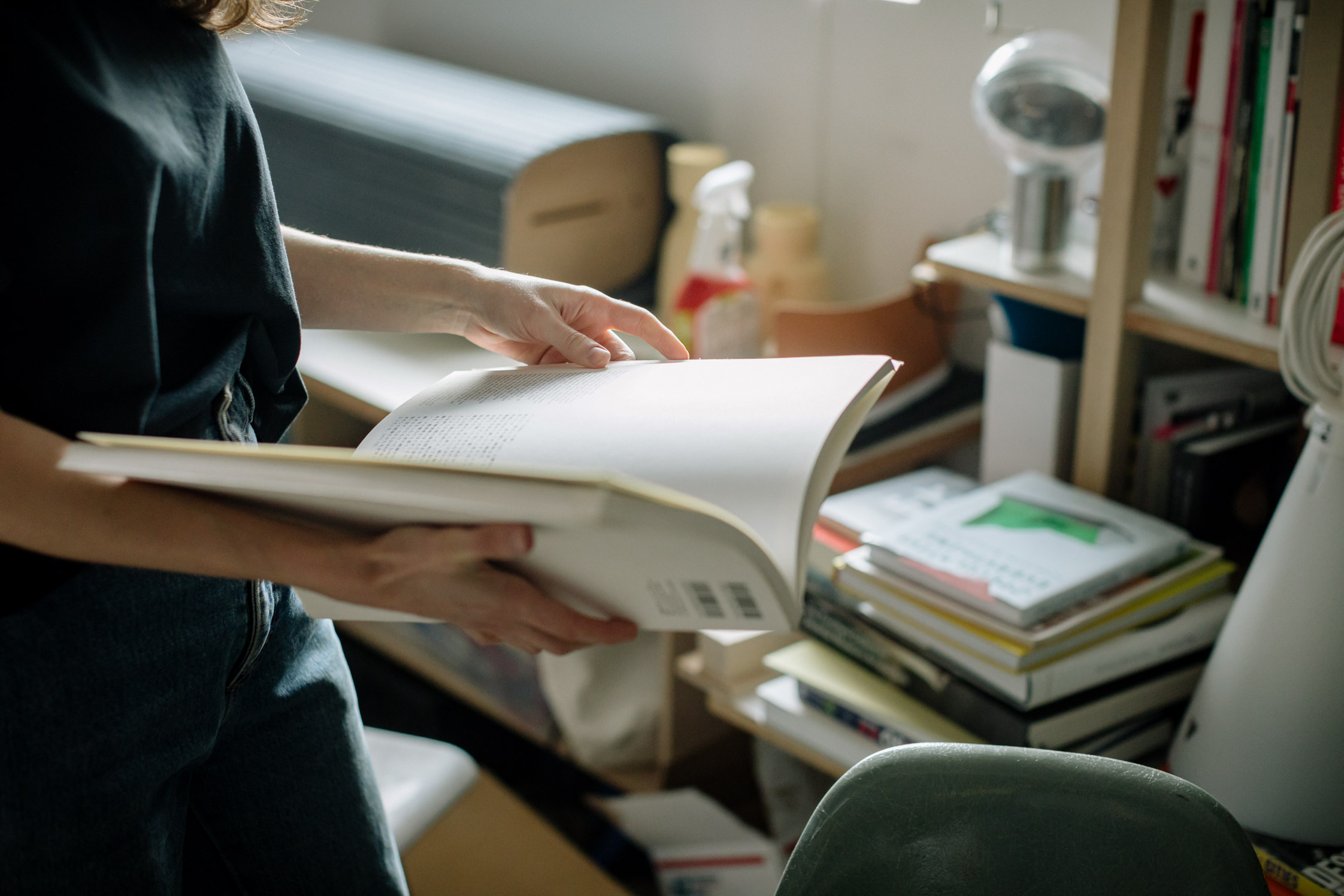

Teaching a Furniture Design Studio at University of Oregon

In this wood shop Zoë passes on her knowledge

“I have found a nice balance between their worlds: artful output concerned with the human experience.”

How has access to technologies like the internet and 3D printers changed your students’ approaches to design?

Despite changes in technology and the addition of endless imagery on Pinterest, my students’ experience is very similar to the one I had in school. A considerable portion of the students’ design process is low-tech and it will remain that way: design will always happen with pen and paper and cardboard and foam mock-ups. I see the computer as a tool and an essential component of the design process—and a lot of newer technologies can definitely speed up the process—but so much needs to happen before that stage.

Our main project this term involves using and connecting two different materials in a thoughtful way in a piece of furniture, and the students have access to some wonderful resources, such as industrial sewing machines, a glass studio, ceramics, various milling machines and 3D printers, vacuum forming, and a full metal and wood shop. The majority of these processes aren’t incredibly high-tech or new, however, and the students spend a lot of their time working with their hands.

Do you pass on some of the things that your own mother taught you to students?

I hadn’t thought of this but it’s quite possible. So much of what I learned from my mother was subconscious learning, absorbing things from being around her and her practice at a young age.

Perhaps one thing that I’m aiming to translate is the importance of exploring and working ideas out in three dimensions. This may go back to my days in my mother’s studio where I spent my time assembling various materials and forms into small sculptures. The directness and immediate palpability of a material, object, or form is such vital feedback. Sketching on paper can only take you so far, so I ask the students communicate their ideas in various sketch models in order for them to fully explore their concept in three dimensional space. I usually refuse to look at computer models if they don’t have a physical one as well.

You’re based in Montreal but staying at Oregon at the moment: How do you manage to keep your business running while you are gone?

It’s possible with a very organized schedule from day-to-day and a lot of emails to a number of very dependable individuals in various timezones that I’ve grown to trust and rely on over the years. My design process and practice has taught me to balance a number of varied projects at once and I enjoy that I’m never doing the same thing everyday. Teaching in Oregon has been a good opportunity for me to step back and think about design instead of only simply producing it—to consider the inputs as well as the outputs in the design process. And it’s been wonderful to miss out on Montreal’s trauma-inducing winter months!