Picture Sydney’s famed harbor and there’s a good chance that what you’re seeing is the Sydney of Ken Done: vibrant, colorful, sun drenched and childlike.

Known primarily for his painting and design work, Ken is a household name in a nation that tends not to shine too bright a light on its creative practitioners. He’s big in Japan, too.

From a barefoot boyhood spent scribbling in notebooks in rural New South Wales to a relaxed semi-retirement now in Sydney, at least one activity remains a constant: painting. Ken’s talent with pencil and brush was noted from an early age, but the pursuit of his own projects took a backseat as he forged a celebrated career in advertising in early adulthood. It was a chance encounter with an exhibition of the great works of Matisse that eventually crystallized Ken’s calling; he wanted to be a painter. After quitting the advertising business, Ken exhibited his first works at the age of 40. While designing some promotional t-shirts for the show he unwittingly gave birth to what would later become a global design empire (run alongside his wife, Judy) encompassing clothing, art, accessories and home goods sold in 16 stores worldwide.

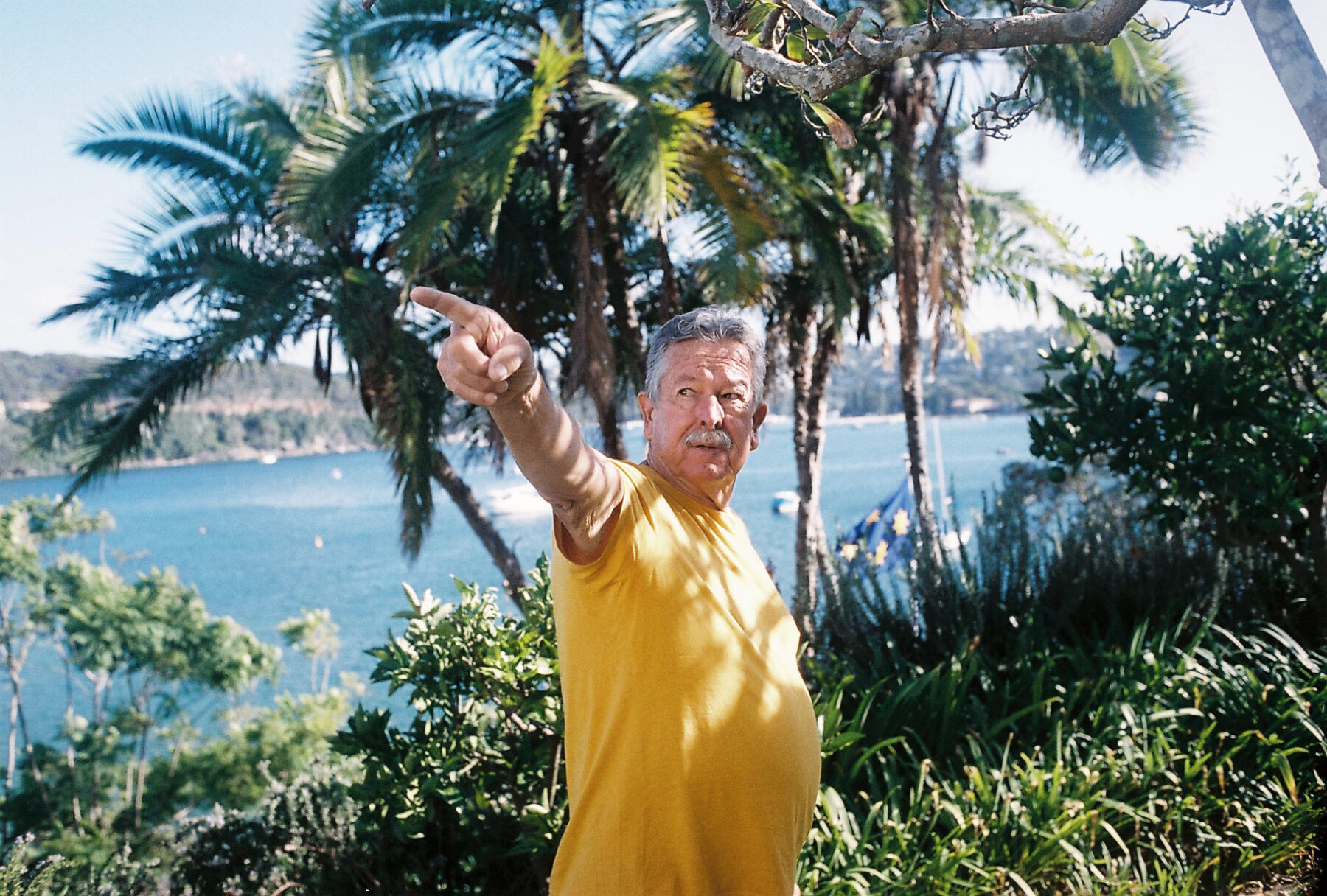

From his brightly lit studio perched on the cliffs above Sydney’s Chinamans Beach, the laconic and irreverent 75 year-old with the ever-present silver moustache continues to paint every day pausing only to swim, snooze and savor the view.

-

You quit a celebrated advertising career at 35 and had your first show at the age of 40. In a sense, you’re a bit of a late bloomer, but we hear you enrolled in art school at the age of 14. Did you come from a creative household?

No. My mother read a lot and my father had been a bomber pilot during the war. When we moved to the north coast of New South Wales, he started a little trucking run, from Maclean to Grafton, and we lived in Maclean for five years. I had a lovely boyhood there. I submitted a couple of drawings of boats on the Clarence River to the ABC – they had a program in the afternoons called The Argonauts. They sent me back a couple of gold stars and I thought, Aw, well, we’re onto something here. I got a special exemption to leave school when I was 14 because I’d passed the Intermediate and I was accepted into East Sydney Tech, which is now called the National Art School. But the answer to your question is: there were no painters in our family, none.

-

Your parents must have shown a great deal of belief in your ability.

They did show a great deal of belief. I’m grateful for all of the things that my parents did, but especially for enrolling me in the art school. We didn’t even know about it at first – my father just ran into a guy once, a sculptor, who said, “He should go and do art classes on a Saturday afternoon,” which I did. And the guy at the art classes said to my parents, “Your son should go to East Sydney Tech.” I think if you have kids who are interested in arts or music, then the earlier they start the better. I might have been an early starter, but I was also a late exhibitor.

-

You’re best known for your Sydney work, which reveals a deep love for that city. What is it about the place, its culture and people, that you love so much?

Sydney is a perfect example of an Australian city, and of Australia’s position in the world. It’s great that even though I live right on the water, a bloke with absolutely bugger all can sit on the beach or rocks in front of my house. The beach is the great leveller of Australia, the great egalitarian space showing that we’re all pretty much the same, really.

This is a remarkable part of Sydney, Chinamans Beach, and not a lot of people know it’s here or how to get to it. This house, which is what used to be the studio, I saw for the first time when I was 14. It was very, very overgrown and I really wanted it. Eventually, we bought it from the lady who lived here and we told her that she could stay for the rest of her life. This is an interesting house because it’s got very good bones, the way that it stretches around and takes the view.

“It’s important to see what you’ve been working on the day before. Sometimes my studio is like an operating theatre and I look in and I see that the patient is in serious need of help.”

-

Surely you’ll never leave.

No, no, we won’t be doing that. The real danger for me around here is real estate agents trying to get us to sell. We never take this place for granted. This is unbe-fucking-lievable. On a day just like today, even though the wind’s come up a touch, we’ve already been swimming down there. We can swim to our front gate. You can’t do this in New York or Paris or Milan. There are very few cities in the world that you can have this kind of lifestyle and also live 20 minutes away from the big city.

We never take it for granted. Even by Sydney standards, it’s pretty bloody good. So, yes, we’ve spent as much time here as possible. We’ve traveled a lot, but this area is obviously a place of continuing inspiration.

-

You’ve said: “In the time in which we live I like to paint paintings that give people pleasure.” What’s your assessment of the time in which we live and is your work meant as a counterweight to that?

Yeah. For instance, at the moment, we are all waiting with baited breath to see if those two boys were executed in Bali. I don’t think that you could make a painting that showed the sadness and fear of that particular experience. For me, it’s clear to see – even going back as far as the Vietnam War with the naked child running away from the napalm, or Rodney King being beaten in LA, or the Bali bombing – that the role of art has to be something that gives people pleasure over a period of time. As a society, I think we’re pretty unshockable. Often, young artists who want to do paintings that somehow shock and amaze people are disappointed that they don’t quite have the impact that they’d hoped for. For me, I want my paintings to be beautiful; I want them to be pretty; I want them to give you pleasure.

-

In contrast, your series on the Japanese submariners attacking Sydney Harbor deals with a fairly unpleasant time in Australia’s history. What led you to explore that story?

I was commissioned to do a series of paintings about the attack while I had prostate cancer. I was operated on Friday, I was home on Sunday, I started work on Wednesday and I just stayed home for the next two or three months doing those paintings. And you’re right, they were subjects that I had not attempted before – death, people drowning, funerals. I even had the great pleasure of taking the Admiral of the Japanese Navy to see them when he was here on a visit. And they were really well received by the critics, too, which I was pleased about – but I was slightly pissed off that people were taking my work seriously for the first time just because it was a serious subject. A bunch of flowers is serious. It’s just a matter of how well you do it. But it’s in the nature, I think, of certain critics to only take complicated and serious subjects seriously.

-

The submariners series, in narrative form and aesthetic, is reminiscent of Sidney Nolan’s “Ned Kelly” series, which you referenced in your work.

I did. I met him twice. He was a fantastic painter. A lot of his work in the end was a bit slick and predictable, but so are a lot of painters’ works. It’s so easy to fall into that repetition of thought – it’s like singing the same song, but that’s all right. At his best, he was just incredibly inventive and understood the Australian landscape perfectly. I think that if you paint the Australian landscape, you have to look at Nolan and you have to look at Fred Williams – lots of other guys, too, but those two especially. I wouldn’t paint the kind of pictures that I’ve done about the Australian beach without respect to what Fred Williams did, about the marks that he made to describe the Australian bush. Same principle, isn’t it? Flat picture plane, dots of color – one meaning gum trees, the other meaning people.

“Often, young artists who want to do paintings that somehow shock and amaze people are disappointed that they don’t quite have the impact that they’d hoped for. For me, I want my paintings to be beautiful; I want them to be pretty; I want them to give you pleasure.”

-

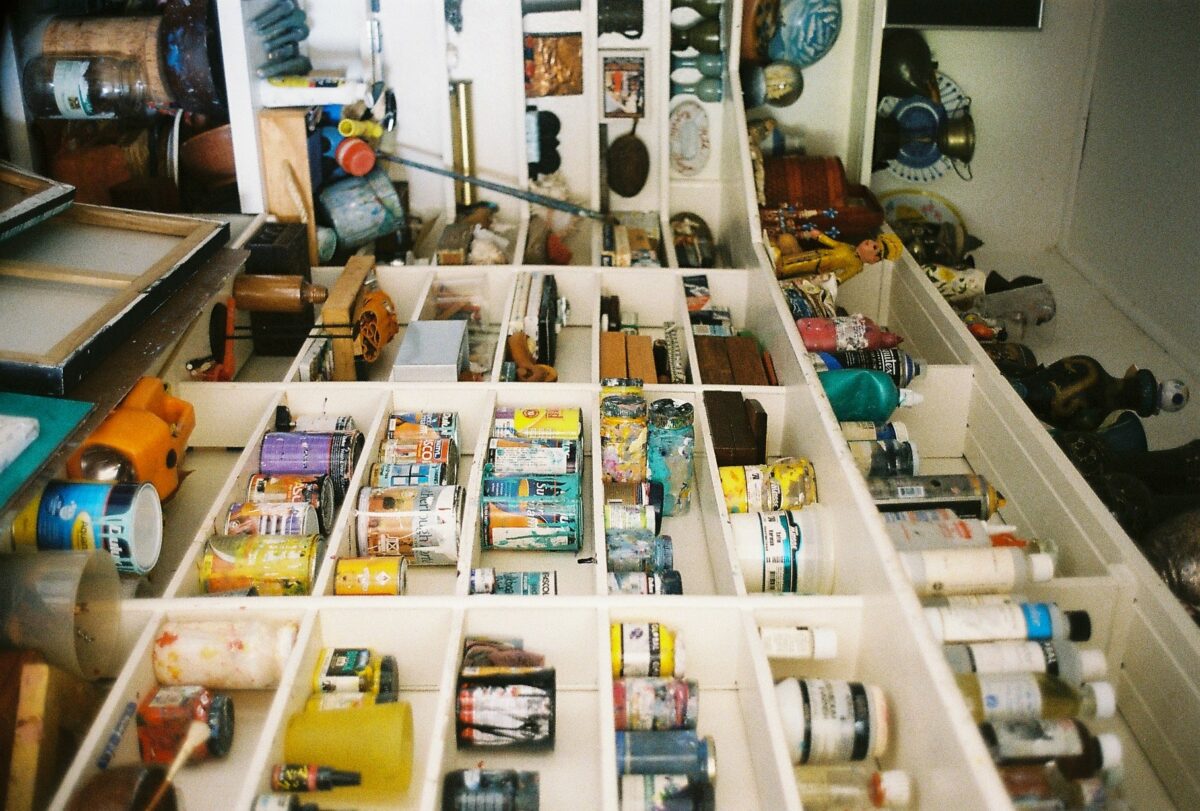

What’s the most meaningful item that you keep in your studio?

The studio, like any artist’s studio, is full of all the flotsam and jetsam that you accumulate over time. For me, the most important thing in the room is the farting gnome. My daughter gave it to me. When I walk out of the studio thinking that I’ve been a particularly clever boy and the gnome farts – that always puts things into perspective. It allows you not to take yourself too seriously.

-

What’s your routine when you work in your studio?

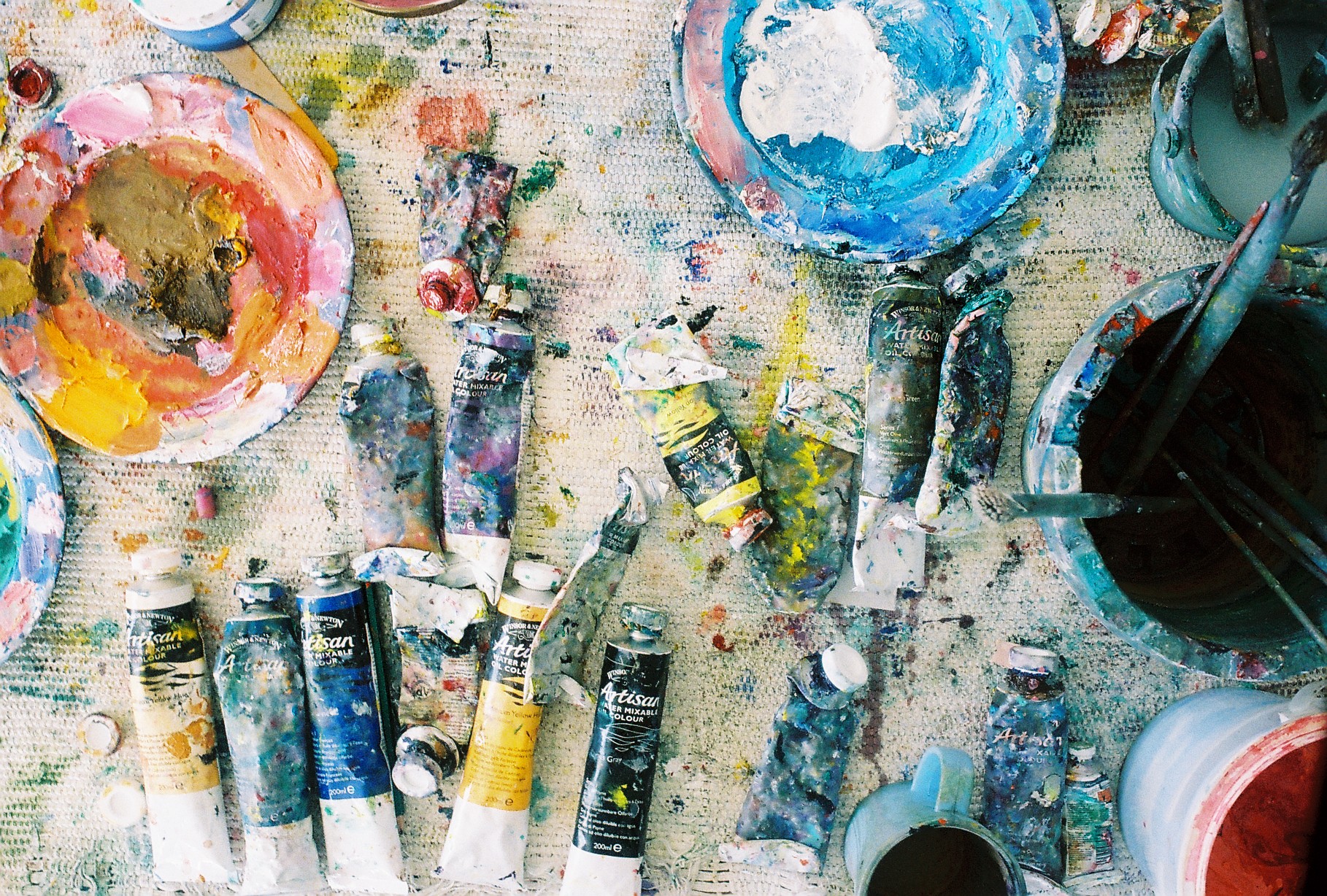

I come down here in the morning and I poke my head into this studio even before I go down to have a swim – it’s very important to see what you’ve been working on the day before. Sometimes it’s like an operating theatre and I look in and I see that the patient is in serious need of help, and I’ll stay here and continue to work until I get one particular part right, or painted over if I think it’s a load of old crap. Then I go down and walk the beach, feed the fish, swim for a while, have breakfast down there, come back and start work at about 8:30. I’m a pretty disciplined worker. I will work till about 1pm; I’ll stop for lunch. I might have a ten-minute snooze after lunch – which might stretch as I get older into an hour-and-a-half – then I come down and work again.

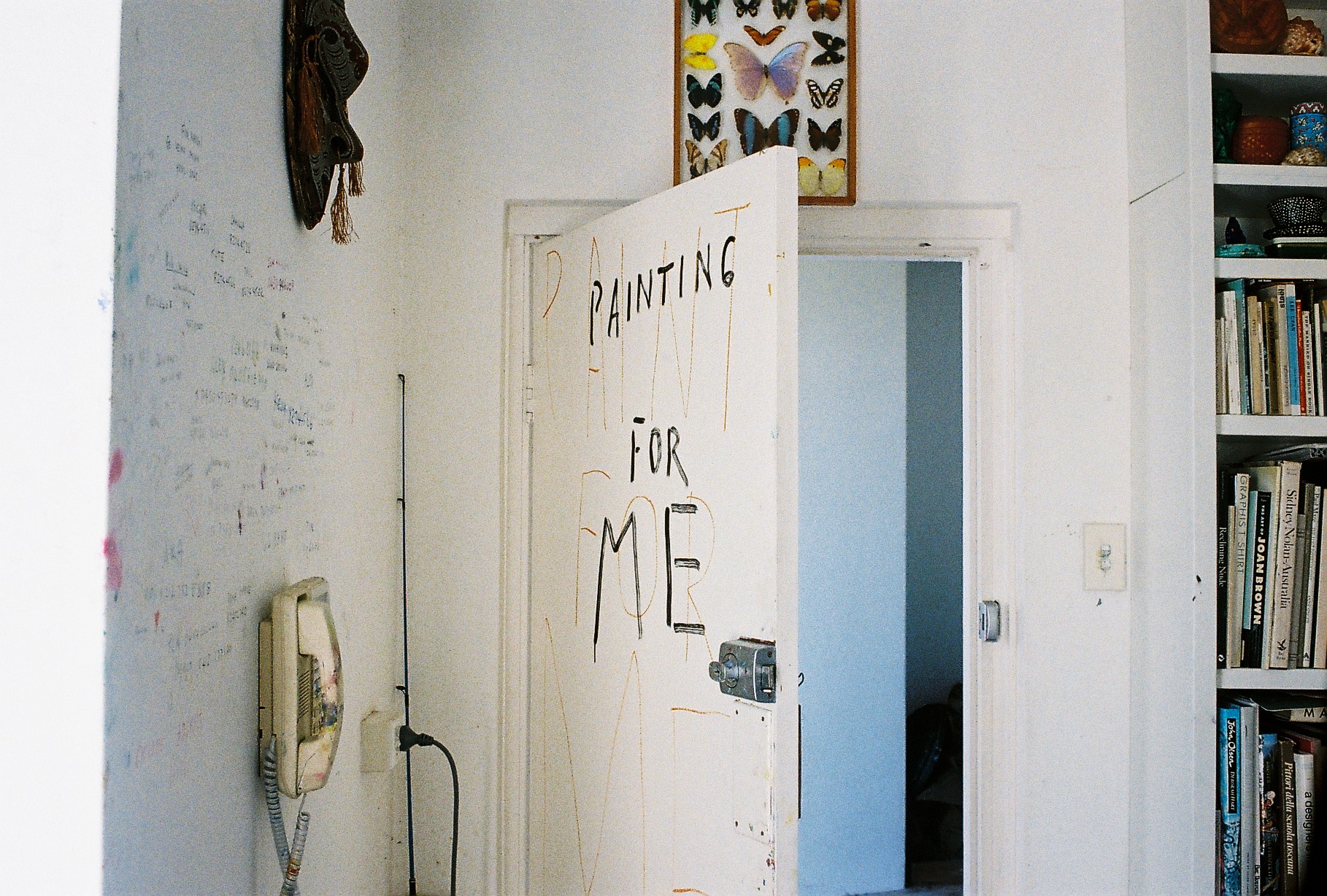

I used the word work twice – it’s not work, is it? It shouldn’t be. On the back of the studio door, there’s a sign that says, Painting’s for me. It should say Playroom, not Workroom. I think that’s one of the great pleasures of a photographer or writer or painter: we’re playing. There’s no point in growing up. You have to keep playing.

-

You called the pieces propped against the wall “failed canvases.” When you fail, do you start again or move on to something else?

In this case, I had four or five goes and it wasn’t very good, so I abandoned it. In the end it was a load of old crap, so I moved onto another canvas. I may not know where this is leading, or that is leading, but that’s also the adventure. That’s the whole thing. I’m not a painter who looks out the window and slavishly copies what he sees. I want to find what’s in my head. We had quite a distinguished English painter come and visit and his first question was, “Wow, what’s the light like in here?” Well, it doesn’t matter, the light’s in my head – I could paint in the dunny.

“That’s one of the great pleasures of a photographer or writer or painter: we’re playing. There’s no point in growing up. You have to keep playing.”

Visit Ken Done’s website to see more of his work. Meet more FvF guests in Sydney.

Photography:James Whineray

Interview & Text:Ché Parker