Michael Zwack has been watching the Manhattan landscape transform since he moved there in 1976. The cityscape that pours into his Kenmare Street studio through the windows, counterpoints the intense paintings on the walls in which, as he puts it, he “paints the whole world.” Zwack’s paintings are sculptural, composed in layers of paint with underpainting, overpainting, abrading, and erasing. They suck you in, as they did to Damas “Fanfan” Louis, a Haitian drummer and houngan (ritual expert) who one day in 1997 brought a troupe into Zwack’s loft to shoot a video.

The art that covered the walls of Zwack’s loft-studio spoke to Fanfan. Powerful, visual, direct, full of layers and nuance, it combined landscapes, symbols, and painted language from widely disparate world cultures. A conversation ensued between the two men who resonate down through Zwack’s work as a before-and-after moment. It led to Zwack going to vodou dances in Brooklyn with Fanfan every weekend. Ultimately, he went to Haiti and became houngan asogwe, the highest level of a ritual expert in the supremely artistic religion of Haiti. He got involved, he says, not so much in vodou as in “the beauty of vodou.”

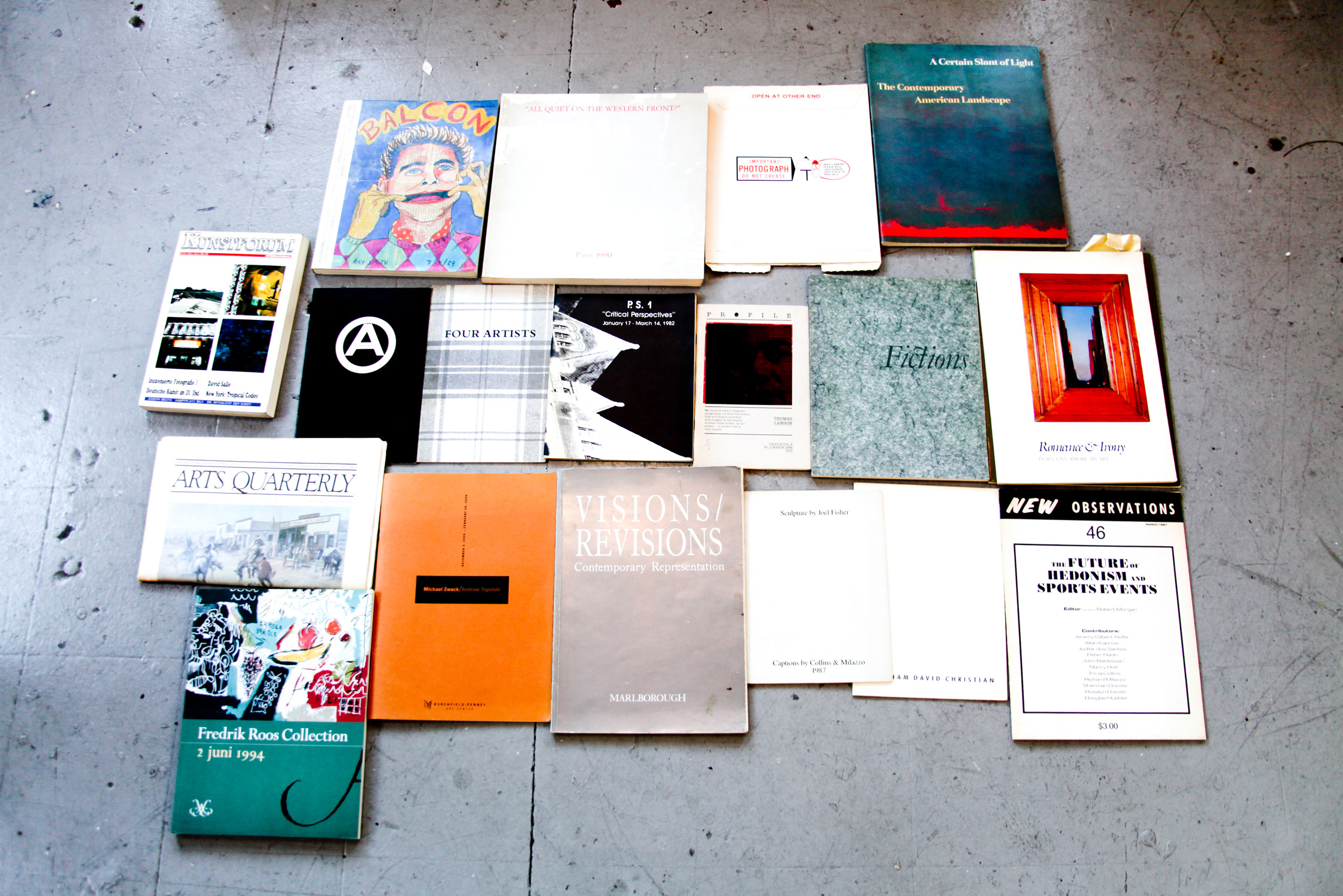

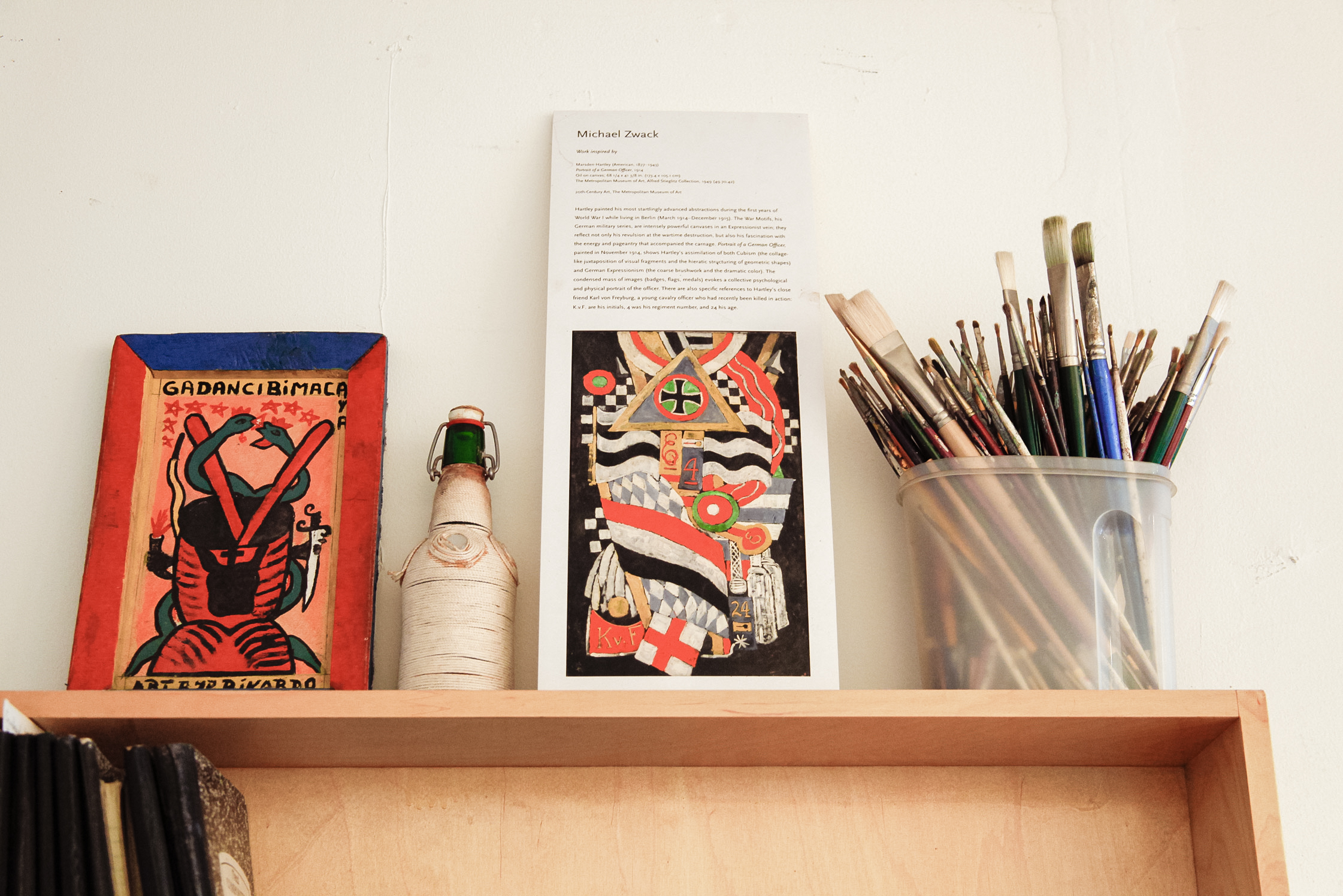

By the time Fanfan showed up, Zwack had already made works that are now in the Metropolitan Museum. Zwack was the soft-spoken odd man out in an art movement that changed the world, erupting out of Hallwalls, the artist-run gallery Zwack co-founded in the 1970s along with Robert Longo, Charles Clough, Cindy Sherman, and Nancy Dwyer in Zwack’s home town of Buffalo, New York. (The Met subsequently branded this group as “The Pictures Generation.”) Zwack’s Haitian turn didn’t radically alter his work, but his insider’s knowledge of vodou gave him a deeper vocabulary and a new sense of authority.

When we spoke, Zwack was tired but exuberant, having just gotten off the plane from seeing his early work in the show Wish You Were Here: The Buffalo Avant-Garde in the 1970s at the Albright-Knox in his home town of Buffalo. As we sat in his studio and talked into the night, for a moment I was a rich man in a roomful of Zwacks.

It sounds like you had a step-back-in-time experience last night in Buffalo.

It was a magical kind of evening, in a strange way. It was about a moment in Buffalo where a lot of people were creative ants in this big anthill. People came together somehow. There was a particular moment when there was a lot of creative energy, a lot of smart people, and a lot of great art being made. Most of the people, who were there at the opening last night, made the art that was in the show.

Who were the founders of Hallwalls?

Charlie [Clough] and Robert [Longo], for the most part. Cindy [Sherman] probably contributed the third, but it was Charlie and Robert’s little brainchild.

But you had a role in it.

I was there. I had a role in it, but as a worker, for the most part. I was making art, and a lot of the art that was created, was made within the moment of founding a space, creating a community of artists. It was a show about a special time, when a lot of important things happened that shaped the art that everybody’s involved in right now.

You and Charlie were native Buffalonians. What’s Buffalo about the art?

There was a lot of space in between people. Business was slow, so it was a very friendly place. Collectors, museum people, gallerists – in Buffalo there just aren’t too many of ‘em. So in Buffalo you’re standing in a room with a lot of people who are there to see the art.

How did you make the transition from Buffalo to this loft on Kenmare Street where we’re sitting now?

I was going out with Nancy Dwyer. And one day she announced to me that she was going to New York, and I said, “Why?” She said, “Well, ‘cause I was always going to New York.” I came here with her.

I haven’t lived any other place since I’ve been in New York but right here in this loft. When I came here with Nancy, a friend of mine handed us the keys. He had this side of the loft, me and Nancy lived on the other side of the loft, and then this other guy Felix lived in this little office. I’m still here.

When I went to Buffalo this weekend it kinda opened all that stuff up. Buffalo is a place where you have a little more space, so you can actually see things and learn things. But you can’t survive there.

So what happened when you came to New York?

I fell into a lot of things, with a lot of creative people. A lot of it started from Buffalo, and it all got mixed together in the ‘80s. Robert moved here with Cindy after that, and everything was kind of getting crazy with all the punk rock stuff going on, you know what I mean?

I remember.

Then Charlie came to New York, and it was… everybody was making art. I would just work. And then Helene Winer called me and asked me to have dinner with her. Over dinner, she was talking about starting this gallery. And I was thinking, “Well, is she asking me if it’s a good idea? What is she asking me?” And she says, “And you’ll be in it!” We’re all gonna be famous in about fifteen seconds! [laughs] She opened up Metro Pictures and then we started to show stuff.

What did you do while you were with Metro Pictures?

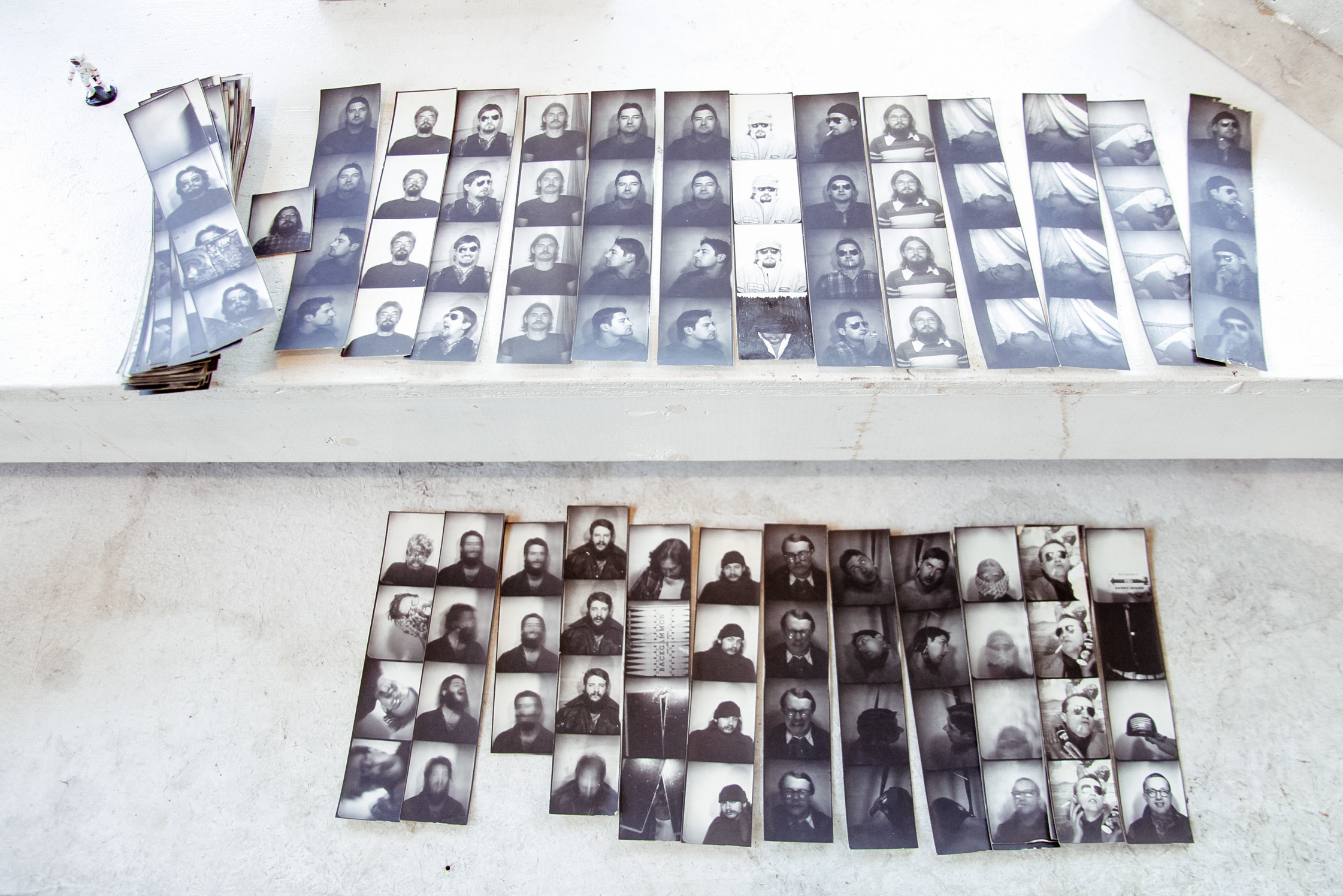

I did the big portraits — these huge drawings that were about 40 by 60 inches. There’s one in the other room, the big giant head. I made a lot of those. Those were drawings that were made on paper of large heads out of using raw pigment that I used to apply with my fingers. And then I started doing a lot of landscapes, working on paper, and people were interested and already, I was completely immersed in it.

I left Metro Pictures and over the next 25 years, I exhibited my work internationally. Somewhere in the middle of that, I started going to Haiti, and Haiti started informing my work.

How did Haiti come into the picture?

What’s now the living room over there had, like, refrigerators and stuff piled up in it. I never used it, it was just this big pile of junk. And my friend André asked if a friend of his could use the space to shoot a video. And so, basically, I said, “sure,” they can do what they need to do, if they help me clean it out.

His friend was Fanfan. The day Fanfan came to my house, I was watching out the window for him, ‘cause I didn’t have a doorbell downstairs then. I saw this guy coming down the street in a blue suit, white shirt, impeccable. I knew it was him automatically. I remember he had these black shoes on, but one of them had a hole in it, and his white sock stuck up through the hole in his shoe. [laughs]

We cut the deal, and cleaned the place up, and then he came here to make his video. My house was transformed when all these people came and changed into traditional clothes. I got involved in the vodou after that. Not so much the vodou. I got involved with the ‘beauty of vodou.’

What do you mean by the beauty of vodou?

How it looks. I got involved in wanting to know more about how all of it works, and I was looking for a system to figure out how to make my art.

I’ve never heard you put it in terms of looking for a system before.

I had continuously been painting – I don’t even know how to explain it – like, painting the world in different kinds of ways. I’ve always been interested in all kinds of culture, and I use symbols and signs pertaining to different cultures in my paintings for years. My art’s always had this spiritual tinge to it somehow. And the vodou – I don’t know how to explain it…it’s so big you’re never gonna have full knowledge of it.

You’ve done an enormous number of paintings that are the horizon and the waves of the ocean. What’s that about?

The ocean draws you in.

This is something you’ve done a lot, just staring out at the sea, right?

A lot. In Mexico, in the Caribbean. Probably the truest painting that I’ve made of Haiti is ‘The Fisherman,’ where the fisherman is going out to get lambi for people on the shore, bringing back fish, and all of a sudden this big Kikongo Kalunga line comes out of the sea like, you know, Mothra or something like that. And also it’s this guy who’s out in the water fishing, and he’s got protection. He’s out there with God.

It’s burning in here. Here I am, sitting in this room surrounded by Zwacks, every one of them a different basic color. Of course, I’m used to it, I’ve been coming over here to see you for many years, and your studio is like a sacred space for me, adjacent as it is to the for-real sacred spaces of your djevo (altars). What’s that one about? [pointing to painting]

The title is Possible Mayan Priest Dressed in Paper Vestments Tical Altar 5. The operative word here is possible Mayan priest, because he may be or he may not be a priest. I spent a lot of time in Mexico in the 80s, visiting sacred Mayan ruins, wandering around solo. In this picture, a priest is dressed in paper garments, for the vision quest. That thing that looks like a carrot is actually a tool he’ll use to pierce his tongue and his penis, in order to bleed on the paper and then burn it. Out of the smoke appears Quetzlcoatl, the feathered serpent. The painting is a representation of the conjuring of a spiritual state. I’m basically trying to paint the abstract, but the only true abstract I understand is God.

Meanwhile, we’re in a society where the market is God. Compared to some of the other artists of your generation who have been very prolific, there’s not that much Zwack on the market, right? And you’re creating these bold new versions of Zwack right now. Where are you going with this?

Hopefully, it’s going to the sublime. That’s where I’d like to go with this stuff, to the sublime. The Mayan Indian there fits that painting, but it’s just one nice painting, and that red painting over here, of Ogou Ferraille [points] is a nice painting in another way. I think I can make big paintings now by combining little paintings — buy some little panels and start putting them together into a big thing.

Are you painting onto wood?

Yeah. Wood panels. They’re all sealed. They’ve got proper gesso on ‘em, all that stuff. Then I put so damn much paint on ‘em, I think they’ll last forever.

Could you talk about your technique of adding and taking away?

Erasure. It makes interesting surfaces. Every now and then I’m working on something and it’s not going right, so I erase it. Then I bring it back again.

Which makes for a kind of 3-D look that we’re not used to seeing in painting. How many layers are there in this Mayan painting?

I don’t know.

I can see four, maybe five.

Well, there’s stuff underneath.

Are you moving away from intense layering and more towards motion? Is that fair to say?

Depends. The limit I’m going to give myself is the size of the things I work on. I could put them together like modules and make big, big paintings that way. Or I could just keep them like exquisite little jewels. But I’m anxious to see more of this, so I have to make it in order to see it. And here I am tonight, I’m back from this thing in Buffalo, back from the 70s. The art that I made back then really gave me a lot of pleasure. And now, seeing it almost 40 years later, it’s holding up. It’s like, it’s art, man. Right now, I feel like I’m just about to hit my rhythm. It feels like I’m entering the moment.

Since the 70s, interviewer Ned Sublette and our guest Michael Zwack have been cruising around the Big Apple and formed a friendship that seems everlasting. They have known each other since the old Buffallo days and explored New York City’s art scene side by side, watching the city and themselves transform along. It’s not exactly a romantic view, but it’s an extravagant, strangely beautiful one.

Thank you for this refreshing interview, Michael! Find more information about Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center here.

Photographer: Grace Villamil

Interview: Ned Sublette