The Norwegian landscape is known for its enormous expanses of mountains and long, winding fjords. Adding definition and design to the country’s sweeping vistas is the job of industrious Norwegian architects.

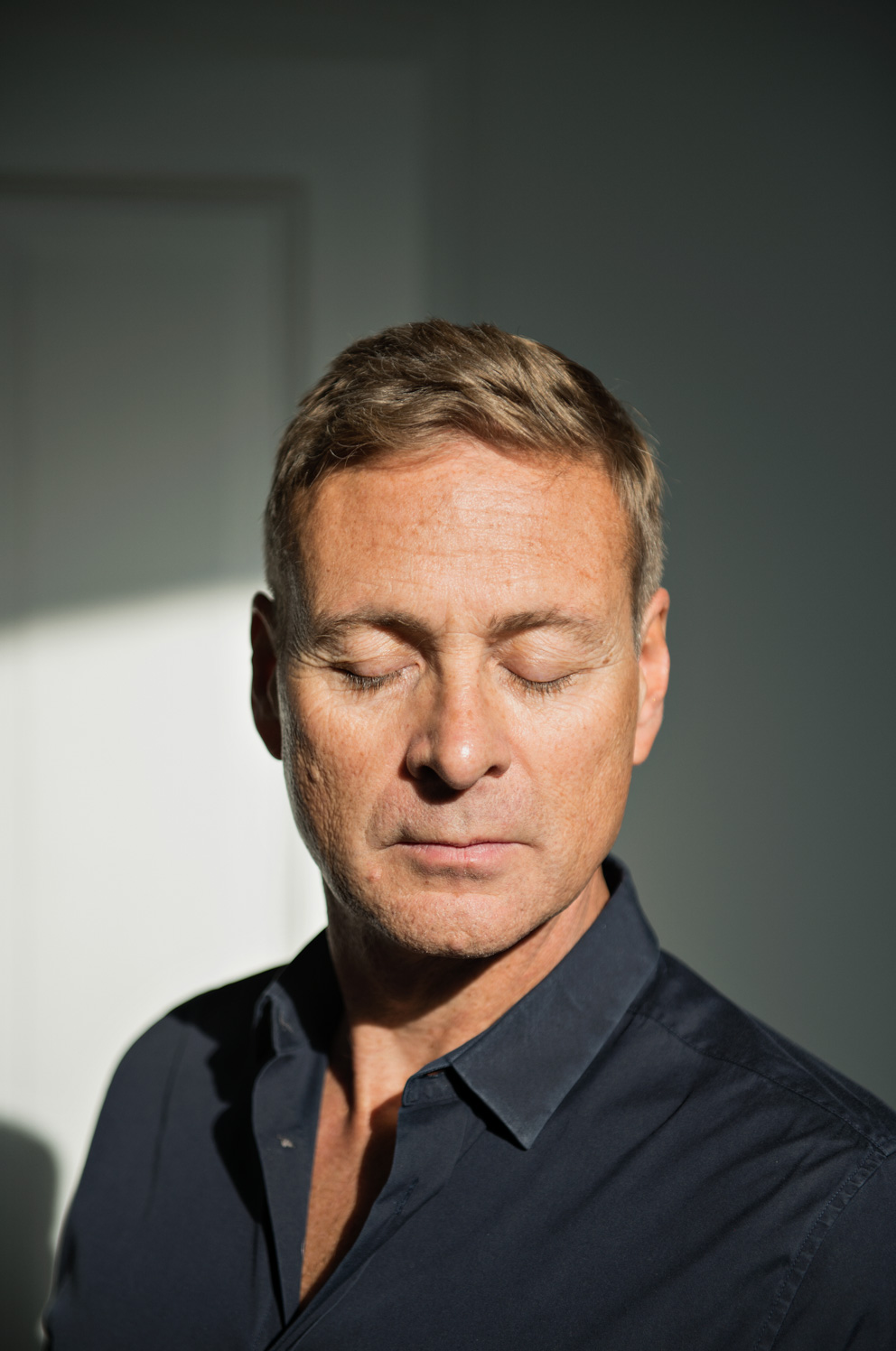

Reiulf Ramstad, head of the Oslo-based architectural firm Reiulf Ramstad Architects (RRA), adheres to a definitive ideology. Founded in 1995, the firm display a humanistic approach in all of their work. “Architecture should enhance the quality of the environment,” Ramstad claims, rather than impose itself on it. This philosophy is reflected in both the use of materials and how the finished design is in a dynamic and thoughtful dialogue with the elements—water, snow, wind—so defining of the landscape and the spirit of the people living in them in the Nordic countries.

RRA conceptualizes the natural space not as a canvas upon which to draw but as a material with which to build in concert. One of the most striking and memorable of their projects thus far has been the Trollstigen National Tourist Route project, which stood out with its open dialogue with the Norwegian landscape and participatory, design. It is this dialogue of design between what is being built and the space that it will occupy, that characterizes Reiulf’s style of architecture best.

The projects that RRA have undertaken have come to define a new Scandinavian style. With cities ever-densifying and urban space increasingly difficult to find there are some intriguing lessons to be learned from Reiulf’s practice. Having designed urban apartments, churches, museums and libraries, RRA, with Reiulf at its head, are championing a humanistic philosophy that can often feel lacking or an afterthought in urban design. Incredibly striking and with sharp geometric shapes, their designs do not shy away from being bold—instead they grow out from their environs as open invitations for human interpretation and engagement.

This portrait is part of a collaboration between Freunde von Freunden and the Norwegian Embassy. Along the way, we’re uncovering the Nordic nation’s way of life: through conversations with leading personalities across creative fields to adventures into the unmissable landscape. You can find more portraits from this collaboration here.

A Dialogue with Reiulf

-

Reiulf, tell us how you started out in architecture?

Originally, I wanted to study ballet but became interested in building through my mother who runs an architectural office. I think that we’re all architects as children: we like building things, even if it is just a couple of blankets thrown across two chairs. I became so curious about architecture that I decided to work at an architecture office before I even started studying. I liked it so much that I decided to become an architect myself. And then I did it, step by step, con amore.

-

How does the sculpting of light influence architecture?

Nordic architecture is very much about understanding where light comes from. We have to work as a composer, hitting the right note with the use of shadows and light, rather than getting stuck in an enclosed space with no connection with the surroundings. Studying in Venice, there was a great sense of light and shadow there. The contrasts are much clearer and crisp, easier to sculpt than here in northern Europe where most days are in grey. But the unpredictability in the Northern light is very interesting, a way of framing light and letting it into the living spaces, when it appears.

-

Architecture has to do with landscape, but also with people, right?

Absolutely and this is where it gets really interesting. Because making a house also means to dig into a place, not just the actual building-site and its surroundings, but the culture and the social setting where it will be located. Architecture is a collective effort, rather than one genius doing the work; I like to involve all people in the process, also the people doing the construction. I like to invite everyone to a party before we begin, then we get to know each other and get a bit drunk: it’s a bit like making a film, the crew is big. It’s the direct opposite of the lonely artist or writer in his cabin, you might say.

-

How does your work attempt to counter a future in which there will be less space and higher consumption?

In recent years, our studio has seen a rebalancing of projects from mainly a public function to an increase in private housing, particularly in our home city of Oslo. In many cases this involves us tackling complex and small sites in the inner city, with a demand for a high-density of dwellings. Of course, we are constrained to minimum space standards for housing, but we also believe it requires great skill and consideration of the architect to make pleasing homes in these conditions. In this sense, we find that we employ much of the same design strategies for such high-density housing projects as we have used in the development of some of our more remote projects—rigorous site analysis, discovering the unique characteristics and qualities of a site, and then working with them.

-

Can architecture create spaces for a more sustainable future and enable a better quality of life?

Yes, absolutely. Indeed this is a central theme in many of our projects. Firstly, we believe crafting high quality buildings is the best way, we as architects, can create truly sustainable work. If we create buildings that are sensitive to their context and built to a high standard, then they will necessarily become long lasting as their users and communities will have no desire to demolish and replace them. As such, the energy and materials used to construct them is spread out over a far longer lifetime for the building.

Similarly, we believe that by designing and building to this high standard, we can enrich the lives of those who live, work or learn in our buildings.

-

What is the impact of increasing urbanism on architecture and design?

It’s positive. I believe increasing the density of the city is not only inevitable, but desirable. It increases the range and diversity of human activity and interaction in the city. It socializes the city and makes them more vibrant places to live in.

“Architecture is a collective effort, rather than one genius doing the work.”

-

How can we start designing in a way that can change and grow correlatively with new problems like climate change and increased urbanisation?

Designing in a flexible manner is key to creating sustainable buildings, particularly in an urban context. Of course, it is essential to design spaces that work with the brief and users they are first intended for. But it is also important to remember that a building’s life is long, and will outlast the functions and patterns it was first conceived for. In this way, we purposely design our buildings according to simple and flexible spatial arrangements, so that they can easily adapt, grow and even change use over a longer time frame than what was at first envisioned.

-

How is Nordic design perceived, and what characterizes the term Nordic today?

Much of our work explores modern Nordic culture, in particular a contemporary approach to how we inhabit and co-exist with the rugged and vast landscapes of Northern Europe and its Atlantic periphery. Furthermore, we are interested in the shared bonds of the Nordic nations. Despite great variety in terrains, climate, language and culture, we can trace a common thread of humanism and a high quality of life across the Nordic societies. Indeed, recent decades have repeatedly shown the Nordic countries to top the UN World Happiness Report—a measure of quality of life, not just in economic terms, but also in health, fairness, and freedom. These principles are expressed in our architecture and its close relationship with the landscape; an insistence on quality, the belief that it can enrich our physical and mental wellbeing.

There is a real regionalism, a plurality of people and landscapes in this country, which is what really makes it interesting to work here—especially in sites far away from the city. I love this heterogeneity because it shows so plainly that Norway is not one thing. People think that the new and radical is in big cities like New York, but the fact is that conformity is more predominant there than in rural areas far away from the crowd.

-

How would you frame this in a global context? What is distinctive about Norway in comparison to other places in the world?

The fact that there are still a sense of place and room for both people and distinct landscapes makes the North a good platform for working with sustainable architecture. For me, sustainable means building for the ages, taking your time, and not making structures that are unnecessarily big. When people tell me what they want to use their houses for I can tell them that they don’t need 300-square-meters but only 100. To think quality and time is what is needed in a world where both the climate and the amount of people demand rethinking how we work and live.

-

So the ethics are just as important as the aesthetic?

No doubt, very much so. It’s important to work by the standards you believe in, not the urge to make fast money.

-

Do you think that this should be happening or thought about on a global scale?

This is the only way to think. There are a lot of houses that are not only are poorly made, but they are ugly and don’t deserve to last. All things considered, it’s actually important that architecture is fun and and an open collective effort and not some sort of punishment. This could be done on all levels of house–making. Another thing which is important in sustainable architecture is preserving curiosity and a will to do something new, start from the beginning, and not re-using uninspiring blueprints which can kill both joy and quality.

Reiulf Ramstad Architects (RRA) is an independent Oslo-based architectural firm known for creating bold and ground-breaking designs with a strong connection to Norwegian landscape. For more information, see their website. To explore some of their recent projects, see here.

Thanks to Reiulf for dissecting the varied work at Reiulf Ramstad Architects from the Josefines gate 7 house in Oslo, a house that’s reflective of his overarching interest and respect for history and solidity.

This portrait is part of a collaboration between Freunde von Freunden and the Norwegian Embassy. Along the way, we’re uncovering the Nordic nation’s way of life: through conversations with leading personalities across creative fields to adventures into the unmissable landscape. You can find more portraits from this collaboration here.

Production: FvF Productions

Text: Kjetil Røed

Photography: RRA, Ivar Kvaal