What does the Australian mining industry have to do with cloud computing? Meet the artist drawing unlikely links between old industries and new technologies.

The first thing that Simon Denny does when we meet in his studio is to apologize for scheduling our interview on a Saturday morning. “Outside of business hours is often my preference for things like this,” he explains ruefully. “I run a really small team and every minute I can be there with them counts for keeping my little enterprise running.”

On the surface, it might seem like a strange way for an artist to describe his creative practice. But slipping into business jargon is an occupational hazard for someone like Denny, who, although he sees himself as a sculptor, devotes much of his time to the technology sector. “Half of my life is spent with people who are much older than me who work within the traditional realm of sculpture that I relate to,” he says, “and the other half of my world is talking to people starting businesses, talking to artists who are designing browsers and working with crazy crypto-like designs.”

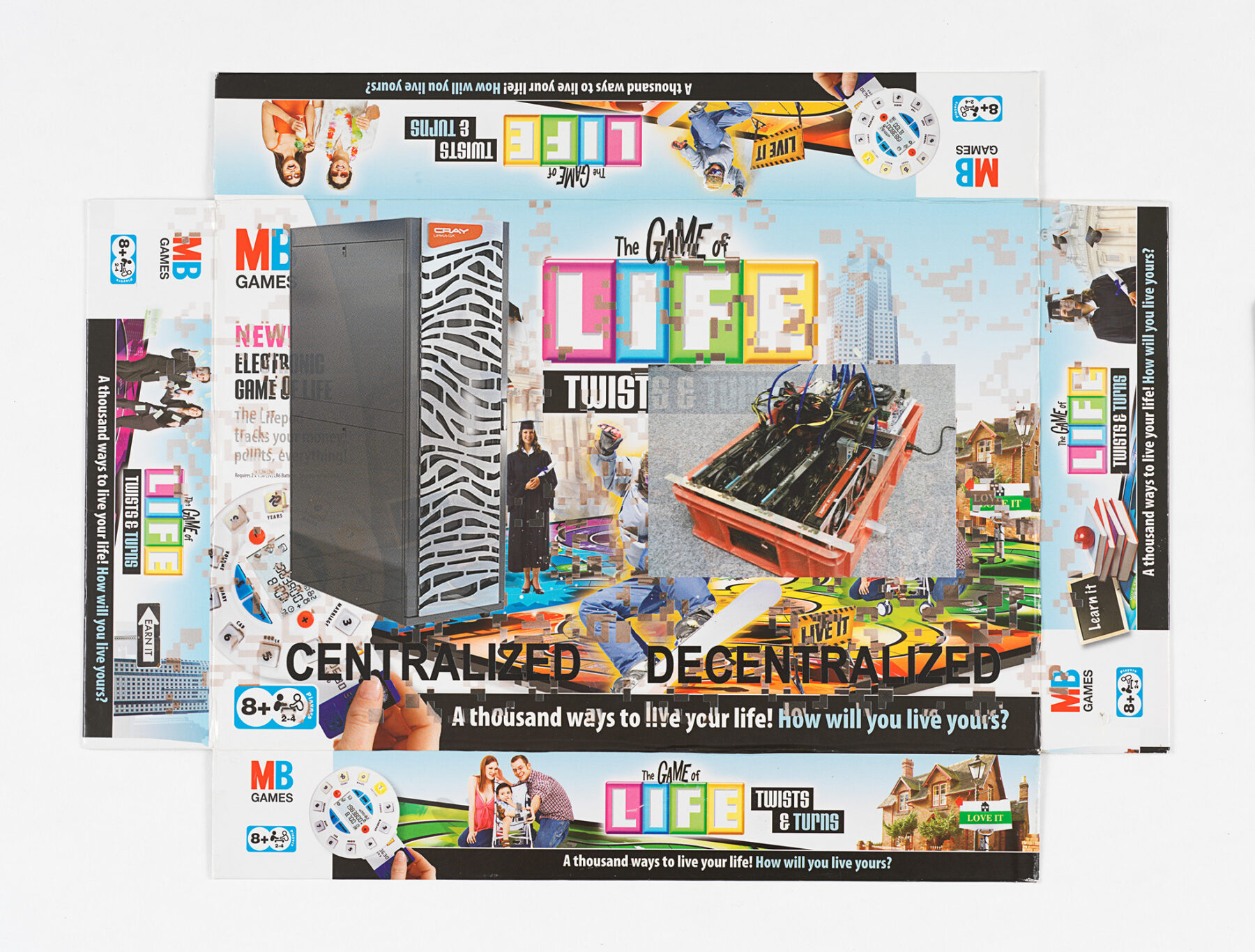

For the past ten years Denny’s research-heavy work has been focused on the gap between what he calls “the stories that are sold to people about technology” and our lived reality. In person, he’s one part tech enthusiast and one part skeptic; a position of ambivalence that carries through to his works themselves, which often mimic the visual language and rhetoric used by the same tech companies he is critiquing. On one wall of his crowded studio, for instance, hangs a work that, at first glance, looks like it might belong in the lobby of the Google Headquarters. Look closer, though, and it’s possible to see that, despite its high-tech aesthetic, the piece takes its form from something much more analog—The Game of Life, one of America’s first popular parlor games. It’s one of an ongoing series of works that use the format of board games to map out complex concepts and histories relating to technology. “This particular piece was looking at some of the forerunners to what is now dubbed ‘crypto economics,’ so the economics of crypto,” says Denny.

The 36-year-old artist first became aware of the existence of crypto currency in 2011, which “friends were using to buy various things from the internet,” but it wasn’t until he was researching the history of hacking for his solo exhibition at London’s Serpentine Gallery in 2015 that Denny “really fell down the rabbit hole.” He was both excited and doubtful about what he read: “The big claim with Bitcoin is that you don’t have to have a trusted entity that allows or disallows things. Instead, you have this kind of distributed network,” Denny explains, referring to the fact that blockchain, the database that underpins all digital currency, validates transactions through a network of computers, known as “nodes,” rather than a central entity such as a bank. “The claim is ‘yeah, we don’t need bankers; we can design the software so that all the rules are hardwired into the way the network works,’ but I was looking at those types of narratives and trying to unpack them because, of course, why should software designers be more trustworthy than bankers?”

“There were moments pre-and-during the Obama presidency where I sort of swallowed the narrative of things moving in a positive direction.”

The emergence of Blockchain technology has caused a flurry of creative production over the past decade for technologists and artists alike, many of whom see this technology as a potential return to the early days of the internet before the distribution of information was monetized by big business. Recently, Denny brought some of these protagonists together in an exhibition he organized at Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon. “I saw this very vibrant community of people working in and out of Berlin on blockchain. And so I was like: ‘ok this has to be something,’” explains Denny. Titled Proof of Work, the pieces included in the show ranged from playfully critical to cautiously optimistic about the potential of Crypto and the blockchain. At the center of the exhibition sat two huge bubbles, Tropical Mining Station by architecture office and blockchain startup FOAM, which were inflated by air expelled from the exhaust of a Ether “mining” machine (specialized computers that process and confirm cryptocurrency transactions in exchange for cryptocurrencies, such as Ether from the blockchain platform Ethereum.) The bubbles offered both a utopian proposal for a type of distributed, decentralized form of architecture and showed the incredible amount of digital energy currencies waste—Bitcoin mining, for instance, currently uses as much power as Ireland.

Born in Auckland, New Zealand in 1982, Denny might now be considered one of the leading figures of a generation of artists looking to the tech industry for inspiration, but he first gained recognition in his home country for making room-sized installations from objects he’d bought from junk shops. “I was using plastic tablecloths and weird plastic objects, bags, balloons and wrapping paper—junk but new, ” says Denny. It’s a far cry from the types of materials he favors now—using wall mount server racks (standardized enclosures for holding multiple electronic equipment modules) as frames for his works has become something of his trademark—but Denny’s background in sculpture distinguishes him from many of his fellow artists who began by making web-based art and then moved into showing their work within exhibitions. “My starting point has really been that I’m an object maker, that’s what I do,” he says. “I look at that history a lot. I’m a viewer of art, you know. I’m a fan of painting; I’m a fan of sculpture; I’m a fan of installation.”

“I saw this very vibrant community of people working in and out of Berlin on blockchain. And so I was like: ‘ok this has to be something.’”

Over the years, Denny has matured from something of a tech enthusiast—once telling The Guardian that he made work from the position of a “fan”—to a more balanced position. “I started my practice and my journey in art being very interested in forms and colors and the way these things work, but as I’ve got closer and closer to this topic, politics has become more important to me,” he explains. This evolution mirrors how the public conversation around these companies has changed more generally: in less than a decade Facebook, for instance, has gone from being seen as a democratic tool (evidenced by its role in the Arab Spring) to a platform that does little to stymie the far-right and religious extremism that spreads there. “There were moments pre-and-during the Obama presidency where I sort of swallowed the narrative of things moving in a positive direction,” admits Denny. “And I think then when we had this recent turn in 2016 people that had been around me started to talk about things in a very different way.”

For his contribution to the 9th Berlin Biennale, Denny chose to display his work in The European School of Management and Technology, which sits in a former council building for the GDR. “What I really liked about it,” he says, “is that there are competing ideologies side by side in a visual form, which is exactly what I wanted to do with my show.”

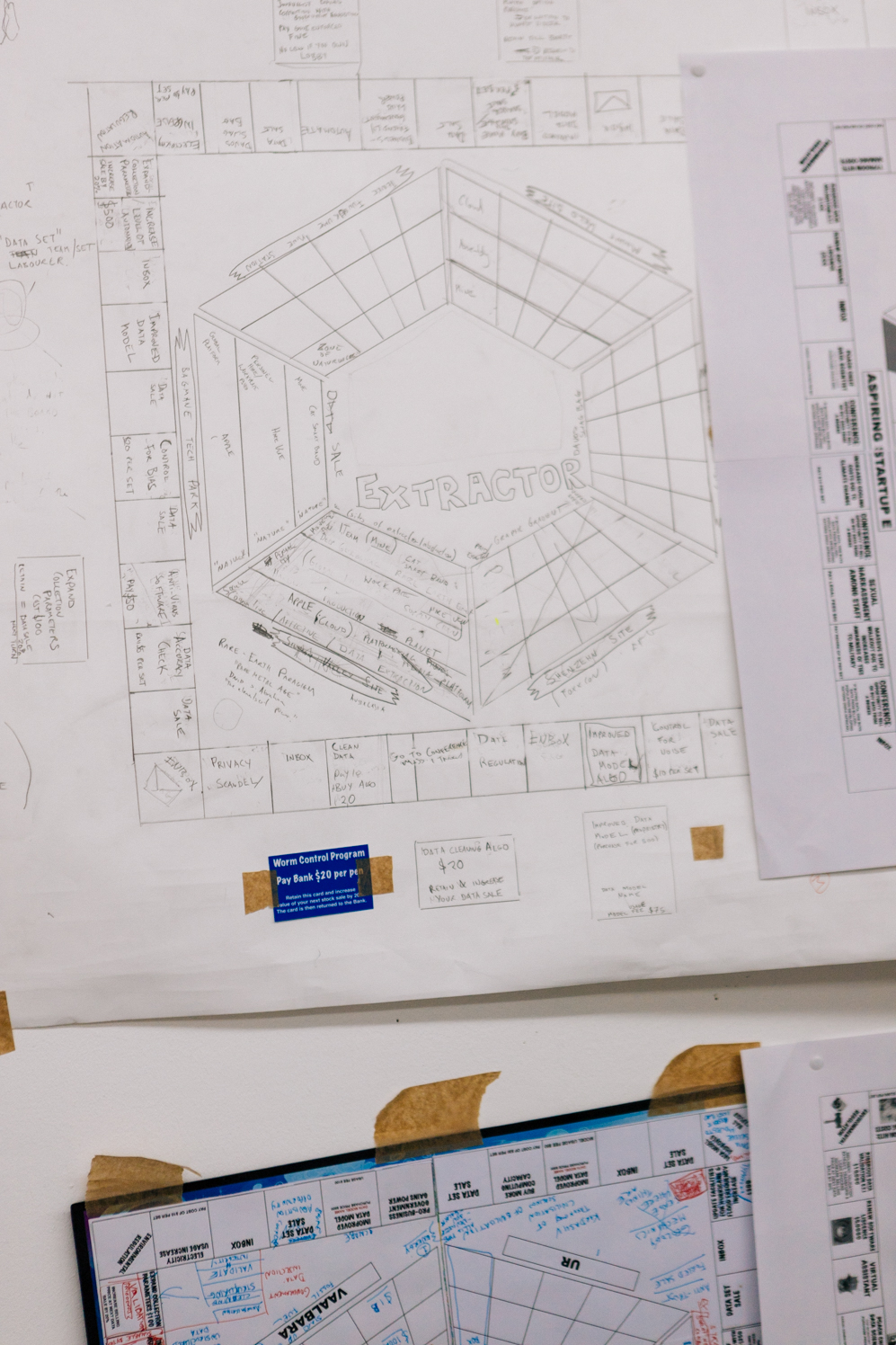

In response, the works that Denny is making for an exhibition at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), in Tasmania, Australia, are shaping up to be some of his most explicitly political yet. The exhibition’s starting point is the popular Austrailian board game Squatter: a sheep farming, Monopoly-style game with, according to Denny, “colonial undertones.” The aim is for players to buy and sell sheep and be the first to improve and irrigate their pastures, while avoiding being hit by natural disasters, such as drought and bushfires. True to form, Denny’s version of the game creates a new narrative that uses data in place of sheep. “You have different platforms competing to take over the monopoly of the world,” says Denny. “And so you have an entertainment platform, a mobility platform, a finance platform, a search platform, a social platform or a retail platform all vying for control and monetization of data.” The game also mimics the real-world way in which our data, now unarguably one of the world’s greatest resources, is stored. “You accumulate data on different kinds of cloud services, so you start with like a free tier cloud, then you should move to a paid tier one, and then you kind of build your own proprietary cloud.”

In the middle of Denny’s studio sits a prototype for a sculpture that will act as a display case for his version of Squatter. It’s based on an automated mining unit; a piece of kit which is increasingly being used in Australia, a country where mining is still a significant primary industry. On one side of the sculpture is an illustration of a fit-bit type of wristband that’s used in this industry to track the energy levels of human workers. “Management can follow your level of fatigue 24/7, and you can kind of be like subbed off when you dip below a certain level of fatigue, which is quite disturbing in my opinion,” Denny jokes. “But it’s part of this kind of data-driven mindset that’s going in to every single business in the world,” he adds.

Furthering the dystopian vibes, the exhibition will also include a human-sized cage that Amazon successfully patented in 2016, which, although it was never implemented, was intended as a transportation system for workers. This depressing device perfectly encapsulates the wider debate about the inhumane treatment of workers in the company’s warehouses and may be the final nail in the coffin for the idea that the rise of AI in the workplace will lead to safer and more dignified conditions for human staff. By drawing parallels between mining as the physical extraction of minerals from the land and the extraction of data, necessary for the success of businesses like Amazon, Denny’s point is that, despite the PR spin, much of the technology industry functions like any other exploitative, capitalist enterprise. “It’s like, ok, it’s not sheep farming, but it has the same kind of colonial and extractive forces behind it,” he explains. “And even when they say it’s ephemeral, all this narrative around cloud computing, it actually has this deep, material imprint on the world.”

Simon Denny is a New Zealand-born artist based in Berlin. His solo exhibition ‘Simon Denny: MINE’ will run from June 8, 2019–13 April, 2020 at the Museum for Old and New Art, Tasmania, Australia. Denny is also in a number of upcoming group shows, including the Vienna Biennale for Change, which opens later this month and the Fellbach Triennial, which opens in June.

Looking for more on Berlin-based artists? Check out our interview with photographer Emeka Okereke.

Text: Chloe Stead

Photography: Jenny Peñas