With its snow-covered hillside and shimmering lake, the Vallée de Joux looks like any postcard-perfect Swiss landscape. But, first impressions can be misleading.

For a long time the valley was known for its harsh winters—a hostile environment for human life. Fleeing religious bigotry in the 16th century, these settlers brought with them their strong spirit of independence. The winters in the valley were long, and as historical irony would have it, it was those with time in abundance who would go on to become the masters of its measurement.

Even today, only a single road winds its way down into the isolated valley. Every once in a while, tourists find their way here—but, for the most part, guests fly in from all over the world to visit the cradle of Swiss watchmaking, as it’s known today. For all its renown, part of the story often goes untold: namely, that the Swiss watchmaking tradition was begun by a group of experimenting ingenues.

Audemars Piguet belongs to these same Swiss watchmakers: founded in the second half of the 19th century, it has preserved its independent spirit in Le Brassus. It’s here that we meet Olivier Audemars, who along with Jasmine Audemars, now carry on the family business of Audemars and Piguet—today in its fourth generation. Growing up only a few meters away from the workshop, Olivier was taken along on regular visits by his grandfather, becoming familiar with the traditional craft early on. The abridged version could read: the grandson follows in his grandfather’s footsteps to carry on the nearly 150-year-old tradition into the next generation.

Yet, the reality was not so straightforward. While both of his sisters pursued careers in fine arts, Olivier graduated in engineering and material physics, and founded his own laboratory. “I am the least artistic one in my family,” he says almost apologetically, explaining that for him physics and art are not so different from one another. “Both disciplines deal with big philosophical questions. You can say that my decision to go into physics is also an expression of my creative self.” Employees at Audemars Piguet agree: he is a relaxed and approachable guy, who loves to tell stories. Fittingly, for the next two days our task is to follow these. Audemars Piguet is full of stories and Olivier knows them all.

“The company belongs to the people who work here—to the watchmakers, to their families and to the entire valley.”

Olivier is pleased to have pursued engineering rather than following the family legacy from the outset. He still runs his own company today, although his main focus lies at Audemars Piguet. “The company belongs to the people who work here—to the watchmakers, to their families, and to the entire valley. We do everything to keep it that way,” Olivier explains on our way to the first workshop. What somehow sounds like a socialist utopia is actually very close to what once distinguished the watchmaking industry: instead of founding independent companies, the watch manufacturers worked in collectives. The idea of differentiating themselves from other watchmakers is relatively new, so too is producing watches in a series. It was only then that watchmaking could become a brand. Indeed, Audemars Piguet only launched their first watch model as a series in 1955. By then, the company had been making watches for 80 years. Even today, there is a three-year development process before a watch goes into serial production, Olivier explains to us as we walk along the banks of the Le Brassus, the river that gives the village its name.

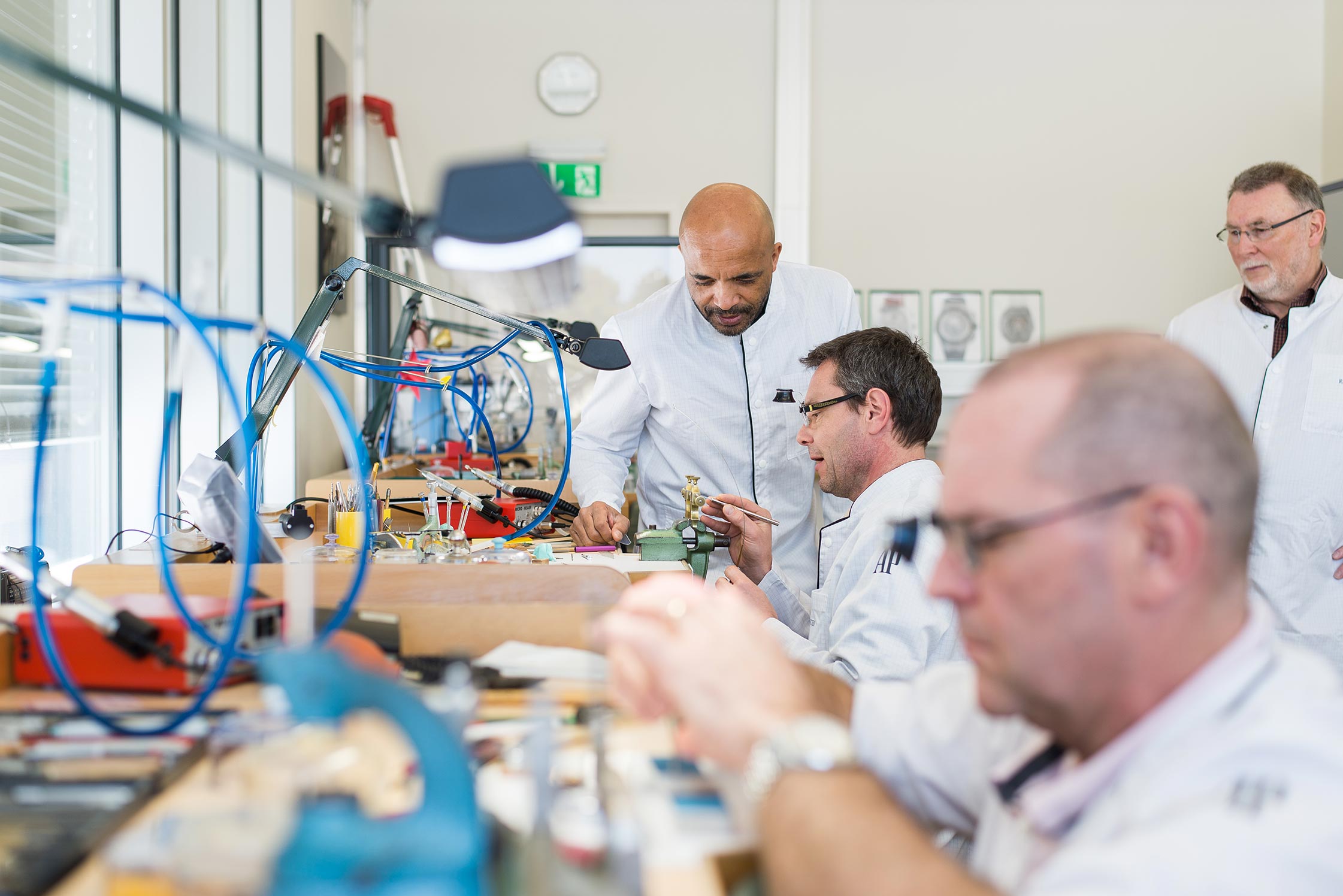

On entering the workshop, we come to understand how a product could become part of a national identity. Over 400 watchmakers and artisans produce an annual amount of 38,000 watches. Comparatively, Rolex produces one million in the same time. We follow Olivier through the halls, a fusion of laboratory and workshop. The equipment on the work benches brings to mind a visit to the dentist. The tools are smaller than expected: an array of tiny pliers and tweezers are at hand at every station, among an inconceivable amount of pieces that fit together to make watches of exceptional value. Take the movement of a Grande Complication, which is made up of 648 pieces. A single watchmaker spends around six months—or 1,000 hours—building the microcosm. “It’s almost like a birth,” Olivier says as he takes glances through a microscope. Most of the pieces are so tiny they are barely visible to the naked eye. Eighty percent of the watch is produced within the company—even for a Swiss watchmaker this is an unusually high amount. The remaining 20 percent come from specialist suppliers, telling of the company’s prevailing commitment to crafting quality timepieces.

Over 400 watchmakers and artisans produce an annual amount of 38,000 watches.

The movement of the Grande Complication is made up of 648 pieces. A single watchmaker spends around six months—or 1,000 hours—building the microcosm.

There were times when only a single watch was produced in an entire year. At one point, there were only five watchmakers left. The families strictly refused to mechanize their processes, convinced it would be a loss in the long term—a foresight that would ring true. Instead of increasing mechanical production, Audemars Piguet placed even more value on skilled production by hand and even in difficult times invested in its improvement. During the Quartz crisis of the ’70s, two thirds of jobs in the watchmaking industry were lost. It was widely believed that the mechanical watch was redundant and the watchmaking art had reached its end.

“We always tried to continue with what we learned from our forefathers.”

Looking back reveals a clear and admirable standing: while part of the industry repeatedly dismissed the panic and became industrialized, Audemars Piguet focused on origin, tradition, and its “Savoir-Faire”: its know-how. “We’ve always tried to build on what we learned from our forefathers, to accumulate our knowledge and with this, become even better.” The remark makes complete sense and in this lies, perhaps, the secret of the company’s success. In particular, it challenges the common definition of innovation: innovation can also be a conscious eschewing of advancements in order to preserve old trades and methods of production.

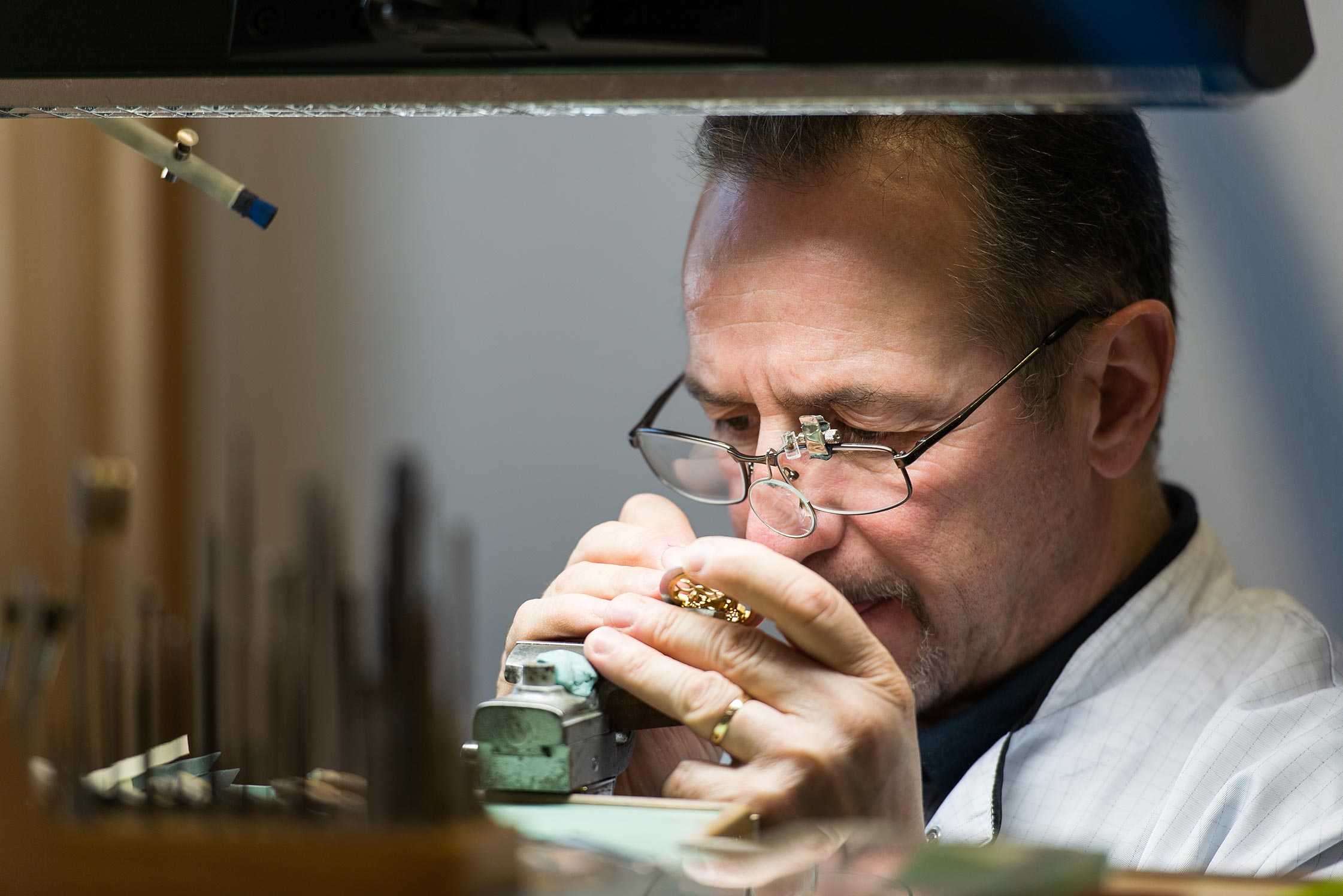

The best place to observe this in action is the restoration workshop, still housed in the original family home of the Audemars. Today a working museum, it’s here we find watchmakers Francisco and Angelo at work. To say that merely watches are restored here would be an understatement: it’s a place where the past is recreated faithfully to the original. The tools and production methods mirror those of 100 years ago. In some cases, Francisco and Angelo must first rebuild the appropriate tool before a restoration can begin. The title ‘Spare Parts Storage’ is slightly misleading: it’s much more a storage for models; the old pieces serving as archetypes to rebuild the originals. Francisco has been in the company for over 36 years. As we arrive at the workshop he is already preparing to go home. It’s 4:00 p.m., and most of the workers are finishing up for the day, ready for a stroll in the mountains. For Francisco, a seasoned New York Marathon runner, it’s off to the streets. “I have a second job as a sweeper,” says Francisco with a laugh as a minuscule spare part falls from his hand. “When you spend 20 hours working on a part like this, you search for it until you find it.” Once a missing part was found in the air-conditioning.

“The watch is an expression of the mastery of the watchmaker.”

The Vallée de Joux is a beautiful place, where the future is shaped through a very vivid past. At the end of the day, Olivier shares the essence of their heritage craftsmanship, “The watch is an expression of the mastery of the watchmaker—it has always been our aim to make complicated watches.” In the case of Audemars Piguet, it’s also an expression of their surroundings in the Vallée de Joux. The valley and the mentality of the people leave their traces on the watches crafted here: the entire world is encapsulated again and again in a single watch, even astronomy leaves its fingerprint on the little universe made of movements and hands.

Thank you Olivier, for sharing your time with us and taking us on a unique journey through the rich history of the company and the Vallée de Joux.

In this collaboration with Audemars Piguet, FvF take a glance behind the scenes of the family-owned Swiss enterprise to learn more about its eventful history and the complex craft of watchmaking. FvF shed light on the Swiss’ cultural commitment, from partnerships with art institutions such as Art Basel to the funding of artists and creative projects.

Text: Antonia Märzhäuser

Photography: Laurent Burst