Katharina Evers and Ulrich Fiedler love, and more precisely live, what they do. Their design gallery, previously housed in Mitte’s Charlottenstraße, has moved to the up-and-coming Berliner art environs of Mommsenstraße in West Berlin. What is significant about Galerie Ulrich Fiedler is that it combines the Rheinland-born couple’s gallery with their home. In Berlin the pair have found themselves living and working amongst classic furniture from the 1920s. Anyone interested in visiting the gallery is required to book an appointment in advance. Once there, guests find themselves in a typical Berliner apartment with a dedicated design section facing the street – gently diminishing interior zones between private and public. Moments after drinking an exquisite espresso and listening to Ulrich Fiedler’s remarks about European design history, clients are able to take the Corbusier couch they were just sitting on with them out the door. The couple only deals in objects that are, as much as possible, in their original state and possess a unique story intertwined with the the history of the piece.

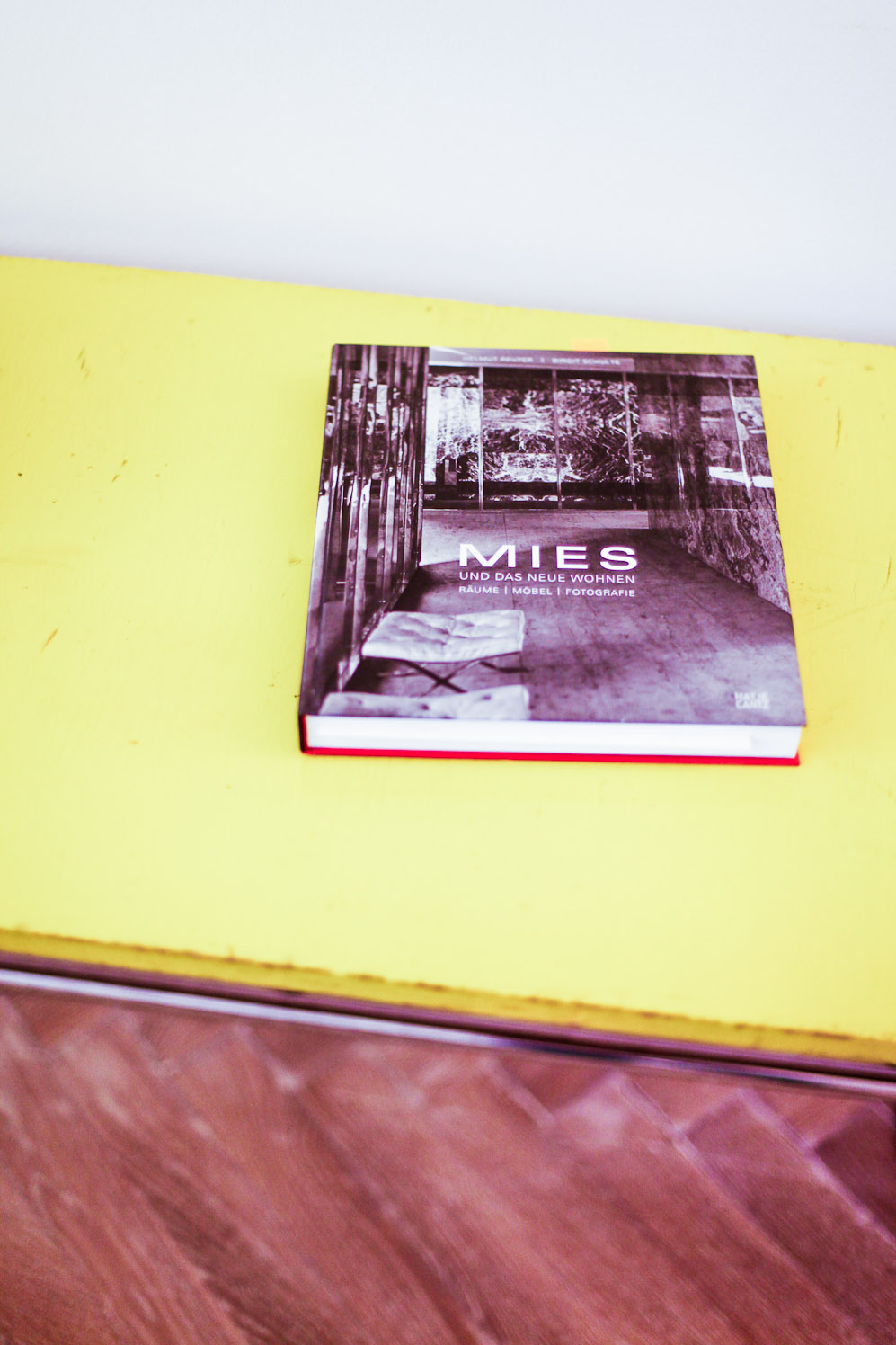

Ulrich Fiedler discovered his passion for design after pulling an eye-catching Mies van der Rohe chair out of a dumpster during his civilian service. The foundations of his enthusiasm for collecting, and later selling, furniture were instantly formed as he embarked on his now characteristic investigation of the object and its history.

This story is featured in our second book, Freunde von Freunden: Friends, order within Germany here, or find the book internationally at selected retailers.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who present a special curation of our pictures on their site.

What prompted the move from a fairly traditional Mitte gallery location to a appointment only home-cum-gallery in West Berlin?

In 2008 we moved our gallery from Cologne to what was, at the time, the upcoming gallery district in Berlin, Mitte. Cologne lost lots of its international relevance after the fall of the Wall. The collectors and museum directors we worked with had a sudden desire to be in the ‘new’ Berlin. We also decided to move to the capital and establish brand new gallery rooms.

I really liked the combination of older furnishings juxtaposed with newer 20th century ones. From this notion of diversity, the idea of finding an old Berliner flat where both elements would be possible was born. We hadn’t previously sold much through vitrines and walk-in customers anyway. Nowadays, we have another kind of window: the Internet. This is how the overall concept came into fruition. We are only able to be reached via appointment and offer quality time to every single visitor.

When did you first come into contact with designer furniture?

I had just completed my Abitur and was in the middle of doing my national service in Aachen, where I used to live. I happened upon a completely rundown armchair in a dumpster that became the very first piece I owned. I was very interested in Bauhaus and suddenly I held an original piece with patina in my hands. It had an authenticity and an aura that no re-edition could imitate. Back then, I used to live in a shared flat and all my roommates were somehow involved in secondhand pieces. They would drive to nearby countries like Belgium and France to conduct business. I would come along and learned a lot about Art Deco and Bentwood furniture.

How did the idea to establish a design gallery that specializes in furniture from the 20th century originate?

To be honest I somehow just slid into it. I inherited my uncle’s flat and as a student it was great to be able to make money by selling some of his belongings. I started financing my collection through my flea market business. I was not able to deal the collector’s items well, as there was no existing market at that time. It all really began when I started to meet other collectors. Among them was Alexander von Vegesack who later founded the Vitra Design Museum. From that moment on, everything became more academic and professional. I bought books and researched history of the objects.

The next big step occurred when I met Katharina. She took care of the organizational stuff, something I was never good at. This is how we founded the gallery in Cologne in 1986, which turned out to be very successful. We started with a big collection of objects that had never been shown in a gallery before. The space was fantastic but four times more expensive than planned. It was a total risk. We were completely broke by opening day. But after two hours we had sold everything. People from museums came by who didn’t know that something like that existed. They were only familiar with re-editions and suddenly all these originals were right there. They freaked out and our entire collection was gone in a year.

So you had to start anew. Where do you find pieces?

This is becoming increasingly harder. One cannot find things at flea markets or through junk dealers anymore. I often buy back pieces that I sold before. I conduct a lot of research and follow the journey of each piece. I know where most of the pieces are that once belonged to me. A large fund has been gathered over the past 30 years. We sometimes also get lucky at auctions. It could be seen as a kind of detective work. If one keeps their eyes and ears open, one might bump into an original Le Corbusier armchair pair that was originally housed in Paris.

Time works against us which is a problem. There are not many original pieces compared to back in the day. When they were working, these designers were so avant-garde that they were unable to go into production. They were too advanced for their time. We don’t take an interest re-editioned objects. We are only interested in early originals, preferably in their native state. We don’t restore the objects but try to conserve and correct the damage respectfully. We have a very good conservator. We don’t buy objects that are insignificant and are in a bad state. At times we only buy fragments if there is no other option and it is an eminent piece. One is able to compromise in cases like this.

How can you separate yourself from an object that requires such laborious detective work?

Finding and buying brings immense pleasure – the selling is more a necessity. I couldn’t afford to keep all these objects. I always say that the collection I would have is housed by my best clients who I fortunately have a good relationship with. This means, I still have access to most of the objects. Unless the objects are far away or in a museum.

Living with the pieces is an altogether different relationship than appreciating them from a distance within a museum setting…

Yes, exactly. We deal with the objects very pragmatically. They are part of our daily life. An object is handled with gloves once it is in a museum. If it is not problematic in regards to conservatory reasons, I keep using the objects. An object with traces of life makes it more attractive to me.

What is the difference between your approach to that of an antique dealer?

Even though we live with things, it is important that it is understood that we don’t sell furnishings in the same way antique dealers do. We inhabit objects and need a collector that comprehends this. It is a collector that buys not because the object would look beautiful in his flat, but because it is an addition to his collection. Someone that understands the object’s significance within design history. Not many clients come here with the intention of furnishing their new home. “Must I have it or not?” That is the question. It is not about the act of furnishing. The historical value surpasses any decorative means.

What constitutes significance for you within design history? What makes one object of a specific era more interesting than another?

Most importantly, we look for the idea within an object. It takes a while to expose that idea but it becomes clearer each day by being constantly surrounded by objects and not just being located in some kind of depot. Depots are like broken utopias. This is something exciting for me. There is a timelessness in many of the objects created. They were thought through to the very last detail. Aesthetics were founded that still relate to the modern age. Many of these ideas were lost during National Socialism. We track those relics down. This 1920s utopia must be apparent within the objects.

You also have an exhibition space in Paris. What is your relationship with the Parisian design scene?

We have built many connections in Paris over the last 30 years. The biggest dealers and many galleries selling pieces from the period we are interested in are there. I know most of the dealers. Many from the time I was hunting pieces in flea markets. Additionally, we are distinguished with our Bauhaus focus as it is rare in Paris.

How often are you in Paris nowadays? Now that you have a real feel of both Berlin and Paris what are your impressions?

I always miss the incredible food markets that you find in Paris when I am in Berlin. I love cooking and preparing dinner for friends. In Paris you can stroll – contrary to Berlin which is so wide. You can explore the city and all the different architectural styles that were built over the centuries. We are trying to come here one week every month, to get the feeling that we also live here. We organize days between business related appointments and friends. We both love Paris and find it special. Furthermore, the traditions of collecting are very different from the ones in Berlin. Parisian flats are decorated very differently. 18th century furniture meets contemporary design and Art Deco, while a Picasso hangs on a wall. The tradition of collection was developed in Paris, something that reveals eclecticism and consistency over many generations.

Everything has a certain harmony. Something that Germany lost due to fascism, which is visibly everywhere you look. In Paris there are families with a certain cultural background that passed on this tradition throughout the generations. A tradition like that does not exist in Berlin or Germany. Especially the Jewish collectors who were expropriated, murdered or immigrated elsewhere.

Do you have any favorite pieces of furniture?

I think that the chair possesses the most expression – this is why we have so many of them. They are the crucial point to every designer. A chair is the object closest to a human. Everybody can make a box. A chair presents several static problems that first need to be solved. The chair is a portrayal of the human body.

Thank you very much for this conversation Ulrich. You can find out more about Ulrich’s furniture and design gallery here.

Interview & Text: Mahret Kupka

Photography: Ailine Liefeld