Manfred Wolf has experienced great success with his practical approach to design. Working with meticulous devotion on his lamps, the product designer places his focus on sophisticated details. His company, serien.lighting, is located outside the city of Frankfurt in an old brick factory building.

Manfred Wolf’s fleet of cars, ranging from the 1950s to the 1970s, is housed right next door. Wolf is not the kind of classic car collector who hides them away in a shed under white sheets, rather he adds his own dedicated touch – restoring the cars to their original state. Even more, he loves to drive the old treasures.

We met him with his daughter Ella in his modern, light-filled penthouse. Over coffee, we philosophize about chance, zeitgeist and, of course, classic cars.

-

You live centrally in Frankfurt’s Westend. What do you like about it?

I like the urban lifestyle and that in the Westend it actually looks like a city. In comparison to other cities, Frankfurt is stress free. I’m really happy to drive here. There are neither endless traffic jams, as in Paris, nor huge distances. The spatial concentration also results in interesting contrasts in Frankfurt. Within walking distance from the clean, quiet residential district of the Westend there’s the lively Bahnhofsviertel, a red light and entertainment district.

-

What made you decide to study product design?

My older sister, who studied architecture in Darmstadt, registered me without my knowledge for student counseling at the University for Art and Design in Offenbach. Design seemed trivial and flashy: I wasn’t engaged with the topic. However, I was fascinated by the the fact that for every product, every drinking glass, a prototype had to be produced. In the past models were made by hand, today this happens through the use of a 3D printer. My sister judged me well, even though the rest of the family doesn’t share my sense of aesthetic.

-

In what way would you say you’re different from your family?

My sister designed classic postmodern-inspired architecture, through their furnishings my parents strove for rustic comfort in a southern German style. I can understand these different positions quite well – people use design in order to project certain concepts onto their lives, but this isn’t my approach. I find a certain distance to design to be important. But that’s my personal preference, everyone has their own perspective.

-

Would you say taste has a lot to do with socialization?

Yes, absolutely. For example, creatively, Switzerland is much further along than Germany. The majority of people there are very well schooled in terms of design.

-

Isn’t design awareness in Switzerland a result of greater financial freedom?

Not necessarily, nowadays you can find good, affordable design. In terms of shaping awareness for form, I consider Ikea as a precursor to the kinds of products we design. Students that buy from Ikea are likely to put more emphasis on good form later.

-

What is your idea of good design?

It’s not about following a trend, because it’s natural for trends to wear out rapidly. In our company we experience the turnover of style very quickly. Once, we gave a lamp a maximum of a ten year lifespan, in terms of appearance. That lamp was launched in 1994 and in exactly 2004 we took it off the market due to a lack of demand.

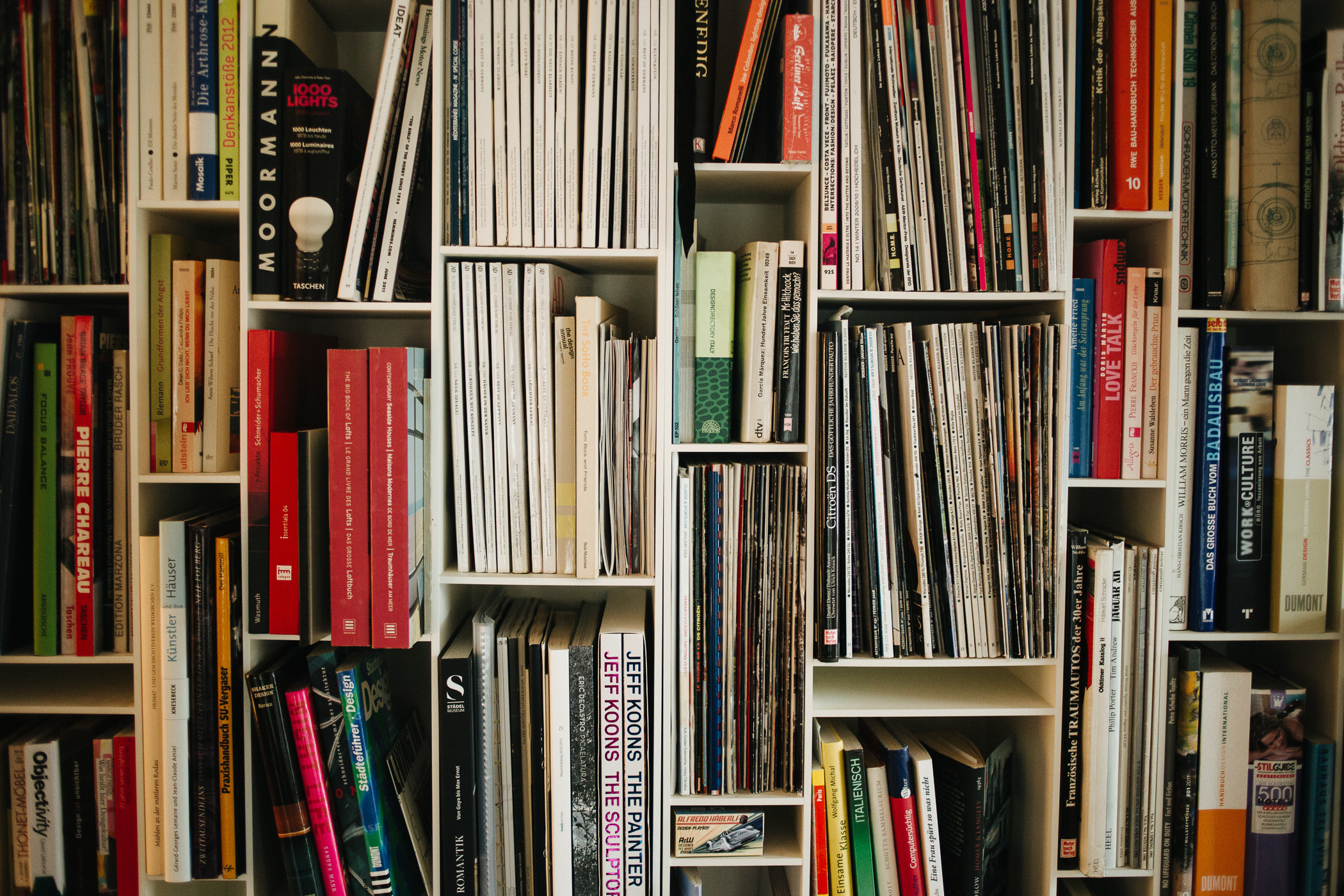

Other designs – like the “Zoom” lamp, which has a sort of fenced structure – are still fresh even after 15 years. Maybe this is because it’s less “formed,” the reduction to basic geometric forms leads to greater longevity. You might like certain design codes today, but in a few years they look dated.

Many talk about timeless design – but design is never timeless. Time always has an influence. We only call certain pieces classics today because they speak to our taste again. In regards to form, which is mainly determined by function, one often speaks of “honest design,” especially in relationship to Bauhaus. Subsequently, product design is oftentimes over-interpreted. It may have simply been the kind of tools available in the studio that, in the end, determined the shape of the product.

-

Why was the first in your series of products a lamp and not a chair?

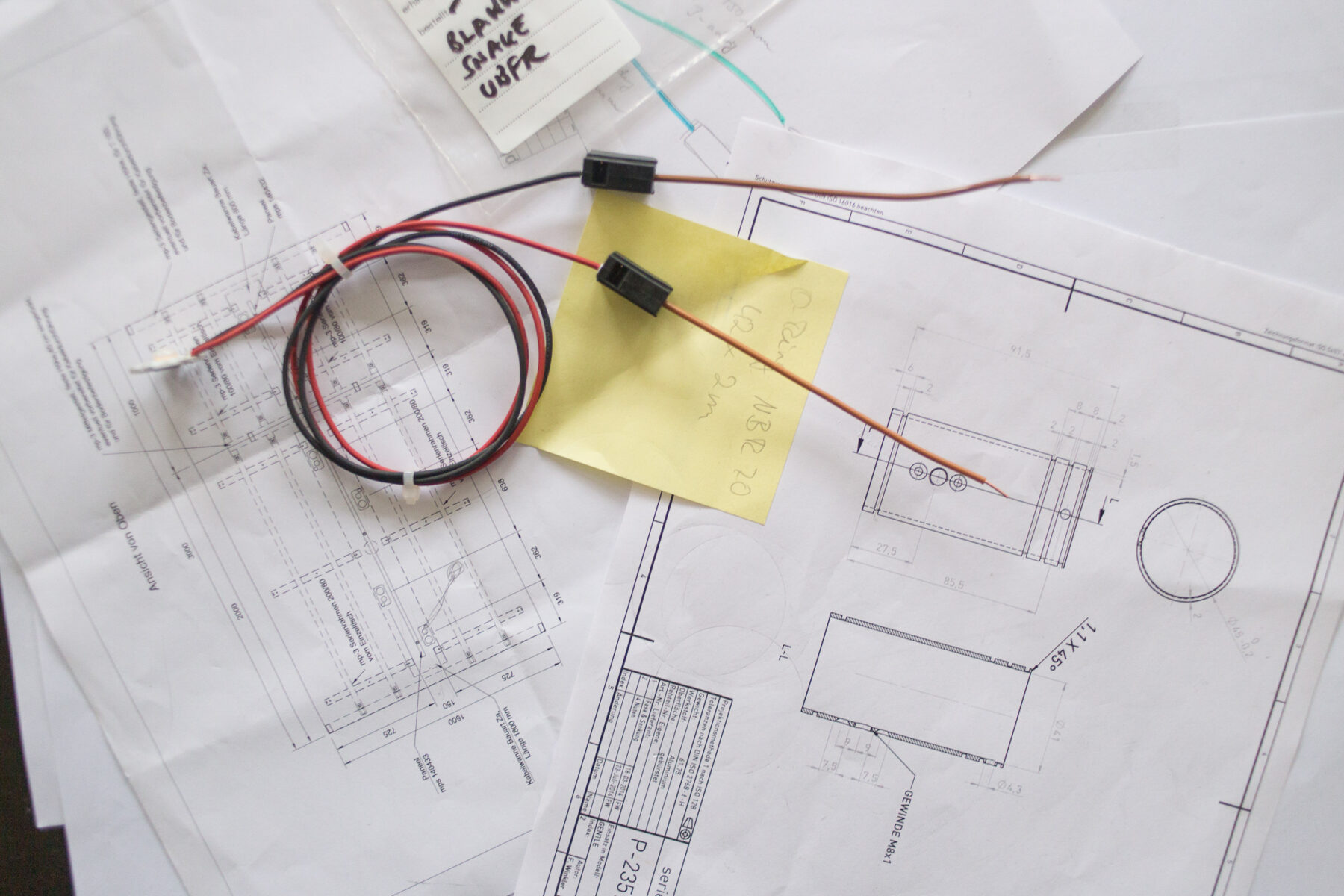

The machines in the metal processing business of my father, which were available to me during my studies, were less suitable for making a chair. I developed my first work lamp out of the materials that I found on the factory premises. The design process can sometimes be quite random.

At my university lamp design was also a big topic. What’s nice about it is that you have to connect the materiality with a static construction and know about electricity and light. A lamp is a refined product that you can also produce on a small scale. With a car a bigger team has to be involved in the design, giant corporations produce it. However, lighting design has changed due to complicated light techniques. Young designers keep it cool, they mostly build lamps for light bulbs.

-

Isn’t the classic light bulb currently trendy?

Yes, now you see a lot with carbon fiber bulbs. But from our perspective, they’re light objects. They light up, but they have little to do with lighting. The light bulb is not really sustainable – and thus no longer appropriate.

-

Where does your passion for classic cars come from?

I like tinkering. In his firm my father had a lot of machines that he had no idea how to use. So he was really determined to make sure that I gained the necessary knowledge of how to use them. My first old car, the Jaguar from 1962, I got by chance. I did the design for a doctor’s office in the 80s – the car was my payment.

-

How did your car collection arise?

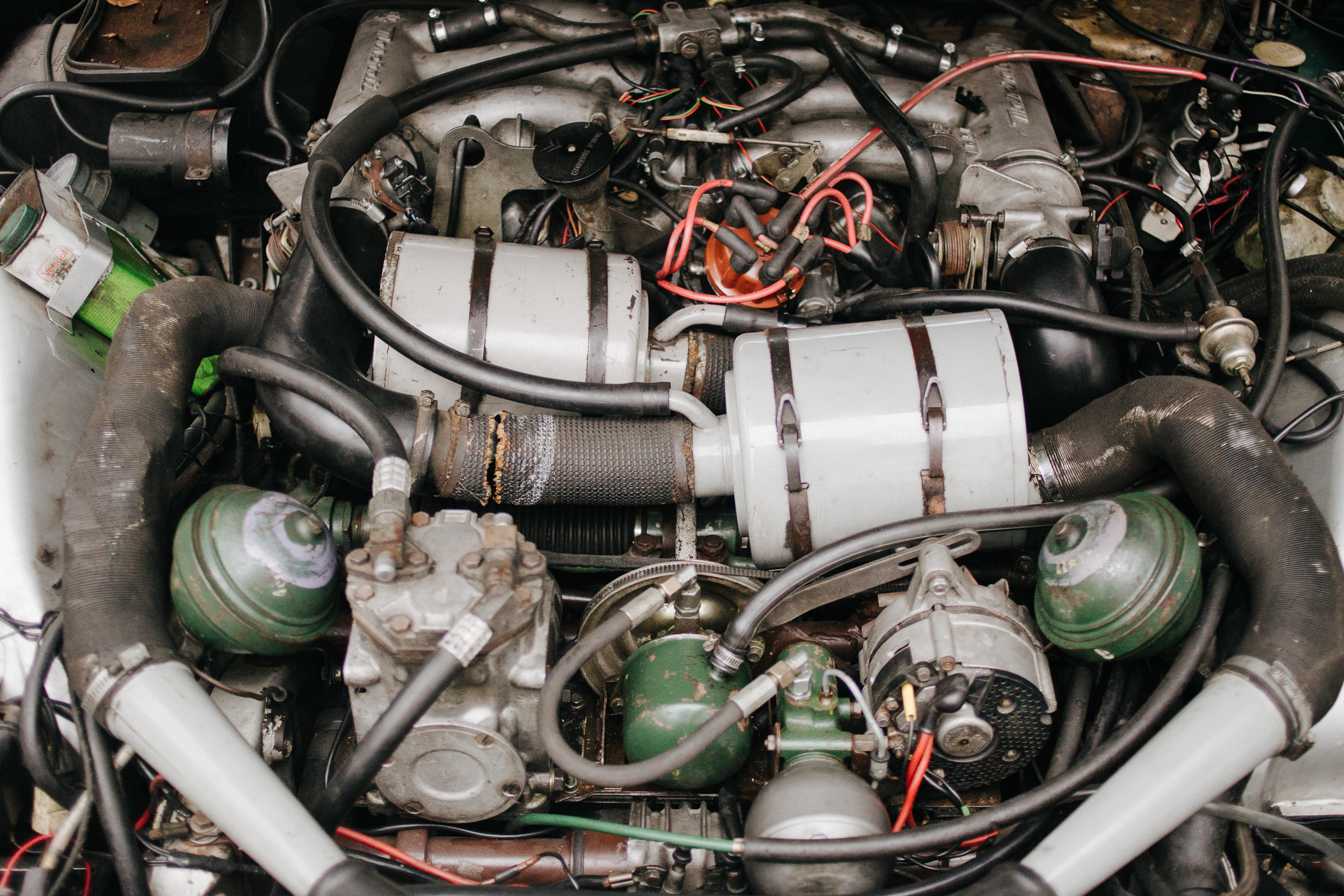

I’m not a typical vintage car collector. I don’t follow a concept, rather the cars accumulated over time. In the 80s, I drove “old cars” from the 60s and 70s. Only later did they become classic cars. It was with the Plymouth in the 80s that I did everything myself for the first time. Researching repairs and putting value on originality brings me enormous pleasure.

-

Why did you choose a Citroen SM?

For practical reasons: With the Plymouth the wiper is broken, the convertible is not suitable for windy days, with this one the heating functions especially well. Sometimes five of my cars function, sometimes none of them. The SM is always my “patient.” It’s my newest car, but has an electronic fuel injection that creates problems. Simple electrical things can be repaired but you’re at the mercy of the electronics. That’s why new cars don’t interest me as much.

His daughter, Ella, interjects: I don’t know how many times we’ve broken down with the entire family on vacation!

You’ll have a lot of adventures with this kind of car and constantly get to know people. Not long ago, I drove a white Citroen DS from Cape Town to Namibia with a friend: over hundreds of kilometers of unspoiled nature. There, you notice even a single fence on the roadside. We had a breakdown, but were quickly on our way again.

-

Do you long for freedom in our increasingly fast world?

Yes, you’re fairly free today, but not completely. As an entrepreneur, I have the relative freedom of being able to decide how to divide my time. For a long time my business partner Jean-Marc Da Costa and I have alternated in two-month intervals as the managing director. I was convinced that I could push my personal projects along in those two-month breaks. But in reality, you sit at a café for two months and let the day pass you by. However, in turn this creates a certain mental freedom.

-

Are you nostalgic?

I often feel like I’m at the mercy of modern technology. When something new breaks, often you can’t do more than just throw it away. Older cars give me a feeling of being in control of what’s around me. Part of my enthusiasm for older technology is about being independent.

-

Do sessions in the workshop provide a balance to your daily desk work?

I’ve always enjoyed working on cars, but yes: For me, the screw has something contemplative about it and it’s enjoyable physical work. Creatively replacing car parts is very similar to the craftsmanship behind product design.

-

What is the most important lesson you’ve learned in your career?

That you have to do things that come from the heart. If your own work doesn’t ruffle your feathers, it’s tough and ultimately won’t be convincing. For me, it’s not about earning money with our company. We want to make our lights. In this respect I understand artists who get deeper and deeper into their work, even if it’s not acknowledged. Because you put a lot of love into things, of course it’s really nice when they’re seen and valued by others – and perhaps this feeling is picked up by others. My friend, Ata Macias, came up with the lovely phrase, “Give Love Back.” That’s why it makes me so immensely happy to discover, for example, our “Zoom” lamp in so many different locations in Frankfurt.

Thanks for the stimulating conversation and the time you took for us Manfred!

This portrait is part of our series “Friends Of Cars” in collaboration with Spiegel Online. See the second part of the story on their website.

Read more interviews with interesting individuals in Frankfurt.

Text & Interview: Juliane Duft

Photography: Ramon Haindl