For three decades the work of Scumeck Sabottka has revolved around the “concert experience,” as he says, to create the “perfect evening.”

After a few wild years in West Berlin’s punk scene, he founded the concert firm, MCT – “Music Consulting Team,” who in their early years organized tours for punk bands like the Ramones or King Kurt, but also for avant-garde musicians like John Cale, and later for international alternative rock giants like R.E.M., Red Hot Chili Peppers and Nick Cave, as well as pop singers such as Lenny Kravitz and Robbie Williams.

The office of MCT is in traditional West Berlin, housed in a former factory where Dinos Automotive plant once made their cars – a more than suitable location for a fan of cars like Scumeck. We met with the 53-year-old in his spacious historical apartment on Meinekestraße for a few croissants with jam. He greets us with a firm handshake and leads us through the rooms. Despite his resolute appearance, the successful concert promoter and artist manager has a unique, almost shuffling, gait – which only intensifies the feeling of warmth he engenders.

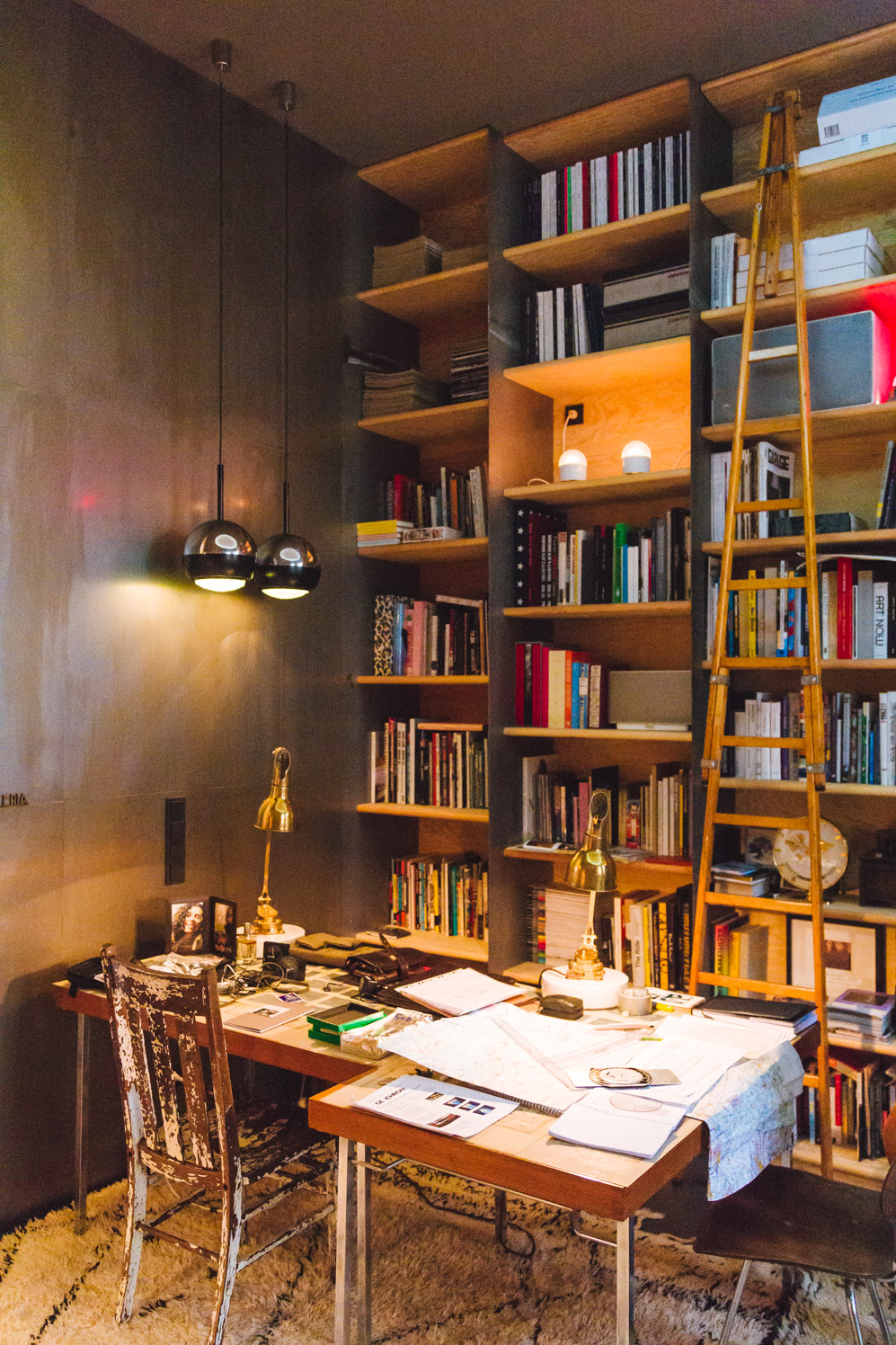

He doesn’t like daylight, Scumeck tells us. He’d rather turn on one of the dozens of dimmed lamps around his apartment. “The best lighting is when they have the effect of small, scattered islands.” Every time we enter a new room, he switches on two or three lights: it’s like a little enlightening ceremony, as though there must first be light to live and think here.

-

Your apartment is in the middle of West Berlin, directly at Kurfürstendamm. What drew you here?

After being a renter for years, at some point, I wanted my own apartment. This one immediately caught my eye. The architect who built it for me, Thomas Kröger, also found it for me. I like it here in the old West. When I was fleeing military service in 1980 and came to West Berlin, I lived on Wrangelstraße in Kreuzberg. At the time, I wasn’t interested in Ku’damm at all. It was only in the 90s that it became interesting for me, when it was a bit more rock n’ roll and cheaper, because all of the attention was focused on Mitte.

-

How important is your furniture to you?

Now it’s a lot of fun for me to consider the details, shapes and angles of pieces. I’m not an expert when it comes to furniture design, but I am passionate about people, their ideas, their concepts of aesthetics. It used to be different. I remember how anxious I was about the price when I wanted to buy my first piece of designer furniture 20 years ago – a used chair. It was Hans-Peter Jochum, who had a furniture gallery around the corner on Mommsenstraße, that showed me that a table isn’t just a table. That these pieces have a value that can’t necessarily be seen at first glance. When people have an enthusiasm for things, like Peter with his furniture, I absorb this passion.

-

What’s your favorite piece in the apartment?

The lamps. I have a lot, almost all of them from Italian designers. I think that Italians know light best. I have quite a few from Gino Sarfatti, who was actually an engineer, and later became one of the most important lamp designers of the 20th century. The first thing I do when I come home is to turn on all the lamps. We wanted to combine the circuits, so that it all goes to a single switch, but it didn’t work. Now I have a Geofencing app that turns on all the lights when I get close to home.

-

For more than 30 years, you’ve worked as a concert promoter. What made you decide to organize tours and how did you get started with MCT in the 80s?

When I first came to West Berlin, I had absolutely no money. I came for the people and the punk scene. At the time Kreuzberg was its own world, an island. I worked in an indie record store, Vinyl Boogie in Schöneberg, and in a wholesale flower market.

It never really worked out financially, partly because at the time I was doing more than a little partying and drinking. Everything changed when I landed in the hospital after an accident and was diagnosed with Hepatitis B. The doctor said to me: “Every drop of alcohol that you drink from this moment on, will shorten your life.”

Because I couldn’t drink anymore, and didn’t want to, but did have a driver’s license, I was constantly being asked to drive. I was suddenly like the seer among the blind. An old friend, FM Einheit of Einstürtzende Neubauten, a West Berlin industrial band, asked me if I would go on tour with the band. I financed the first maxi-single of the Neubauten: Durstiges Tier (Thirsty Animal). I had to borrow the money from my parents.

At any rate, I started out working as a driver, then increasingly as a tour manager for German concerts, at the time for London indie label Rough Trade: mainly with post-punk bands like The Smiths or Cabaret Voltaire. Until, along with Dietrich Eggert and Jochen Hülder, we decided: “Fuck the labels, we can do this better!”, and we started MCT.

-

That was in 1984. Dietrich was the head of Rough Trade Booking and Jochen Hülder was the manager of the Toten Hosen. One of your first big tours was with the punk pioneers the Ramones. Was this more of a job or a dream come true?

We wanted it to be both: To do good work, to organize great concerts, and at the same time to bring bands that we loved to us. Before it worked out with the Ramones, I sent their agent in London a Telex, a predecessor to the fax, every day for a year. Everyday the same message, until he finally answered and the Ramones came to Germany for three shows. A pretty successful tour.

-

Every music fan has a handful of bands that are essential to their musical development and are particularly inspiring – what are five for you?

I don’t even have to think about it: Sex Pistols, The Clash, Throbbing Gristle, SPK and Kraftwerk. In exactly that order. Punk music was influential for me, even though I really only liked it until it reached its peak – and that happened really quickly, at most four or five years in the late 70s. In 1978 I saw Stiff Little Fingers in the Hamburger Markethalle and the UK Subs – these were already run-offs from the big wave. I also remember how angry I was because I couldn’t get tickets for the Clash tour.

Later, I organized my first show in Berlin at Kreuzberg’s SO36 with SPK: It was SPK with Tödlichen Doris and Alexander von Borsig. And, relating to Kraftwerk, I was yelled at by my father, because when I was 12-years old, I called the Cologne radio station WDR to vote for Autobahn during a program of pop hits. This was an expensive call from our hometown of Waltrop.

-

What’s most important to you in your work?

The answer to this question is somewhere between money and emotion: the numbers on paper are one thing. Sure, it plays a roll. But I think that an agent always chooses the promoter that they have a better feeling towards – the one that he believes that will bring his band more because they’ll look after everything to the smallest detail. And that’s exactly what I want to do with MCT: Not as much as possible, rather as comprehensively as possible, as they say in legalese.

I want to take care of every aspect and communicate with the musicians during the preparation process. Not just go with plan A, but to maintain a perspective of the whole. You often have to anticipate how the tour might run a year in advance.

-

Keyword – Kraftwerk: Since 1991 you’ve been responsible for the coordination of their live performances. In the last few years, there’s been a lot of discussion in relationship to the band about the “museumization” of pop concerts because their concerts, such as recently in Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, exist on the borders of performance art.

That’s exactly what is so extravagant about it: the room, the music, the graphics – this should all come from a single place. All the more difficult is to make it look easy. The sound in an exhibition room like the Neue Nationalgalerie is a catastrophe. You wouldn’t believe what we had to take there as far as material goes, just so that these concerts were even possible acoustically, as Ralf Hütter from Kraftwerk imagined them. All the better that it worked. Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie is at the top of the list of desired locations that I have from Ralf.

Despite the huge effort, these concerts are mostly fun. In a lot of museums, at the MoMA or in the Tate Gallery in London, I’ve dealt with people whose concept for these kinds of shows were completely wrong: They think, these four guys dressed in their suits are going to come, roll in a bit of technical equipment and play.

The sheer effort, which museum organizers already know from the exhibitions they produce, always surprises them: because we do it for a night and leave the next day. It’s great when the people are open and work with you to try to bring about the best possible experience. That’s the pinnacle for the concert organizer.

-

How have your professional aspirations changed in the last 30 years?

I think it’s always about the things that I simply didn’t perceive earlier. Instead, I was always busy with just making the company run. We had hard times: There were times I was almost broke, I had to look for new business partners.

Now that the firm is running, you can get a better feeling for certain things: For example, how important a good team is and how much time it costs to take care of a good team. We used to be three or four people in a single small room, now there are 12 of us. You have to listen: What are the wishes, what are the needs? Over the years I’ve learned that bad times can bind you more than the good ones.

-

In this age of MP3s and streaming services, fewer CDs and records are being sold, putting the music industry in a deep crisis. Is the fact that concert revenues are increasingly important for record labels palpable at MCT?

Yes, very much. The pressure has increased dramatically. We feel it every day. The tickets are getting more expensive, because the record revenues are dwindling. To illustrate this with an example: For the last three Massive Attack Tours we went from 24, to 28 and finally to 32 Euros per ticket. The next time we probably can’t calculate for less than 42 per ticket.

What’s expected of us is quite different today. Since we’re responsible for such an important part of the business, the labels and agents put their greed on our backs – especially financially. It was more comfortable before. Rather, let’s say, it was just different before. The music business is always more of a process than a fixed system.

-

Let’s talk about your classic car, where does your passion for old cars come from?

I think it comes a bit from my father. He always drove cool cars: company cars from Audi. My first car was an Opel Kadett that I bought when I was 18 for 500 German Marks. Later, I bought a Opel Commodore two-door with a duty stamp that I was allowed to drive for less than six months.

I liked nice cars back in the 80s, but never had money for them. I bought my first car when I was 30 and then at some point a Ford F100 pickup. It’s only been in the last eight or nine years that I’ve gotten a gotten a bit more into it. I don’t collect cars as an investment, rather because I like to drive. You have to use cars.

-

Do you work on them yourself?

No, I’m not a gear head. I want one thing: to get in and drive. I know how an engine works but I don’t have the time or the expertise for more. I think it’s a lot more fun to stand around and listen to the people who really know about it as they talk shop – like at Classic Wheels in Zehlendorf.

-

Does this desire to drive have something to do with the mythos of the car – this dream of being on the road and the related desire for freedom?

A good question. Sure, I think it’s about movement. But above all the form of movement – a form that others have devised for us. I think it’s fascinating how many thoughts precede us actually sitting behind the wheel. Exactly like with my Pontiac,where the carmaker was inspired by indigenous people. I love how this is manifested in the form of a car and its spaciousness.

-

At the same time you’re also getting your pilot’s license?

Yes, at this point I have almost 200 flight hours behind me. In some ways there are parallels to my work. When something goes wrong in a plane, you’re under a lot of pressure. And either you’re young and driven by infinite passion or, when you’re older, you profit from your life experiences. This is what I’m doing with MCT – staying calm, thinking and following through to the end. I love the thrill.

Thank you, Scumeck, for the enlightening interview and the time you took for us.

This portrait is part of our series “Friends Of Cars” in collaboration with Spiegel Online. See the second part of the story on their website.

Read more interviews with interesting individuals in Berlin.

Photography: Dan Zoubek

Interview: Annett Scheffel