Max Pam is an Australian contemporary photographer. Originally from Melbourne, he now resides in the quiet yet charismatic port side area of Fremantle in Western Australia. Max first visited Perth in the 70s after a brief stint abroad. After traveling extensively in his earlier years and even calling Brunei and London home among others, Max has found his place in Perth. Max’s work is a self described mixture of photography as a contemporary art form and photojournalism. Using a developed technique and a distinctive style, Max has told a lifetime’s worth of stories through a combination of personal journals, paintings and of course, photographs. He has exhibited widely, both locally and internationally, in addition to publishing over a dozen photo books.

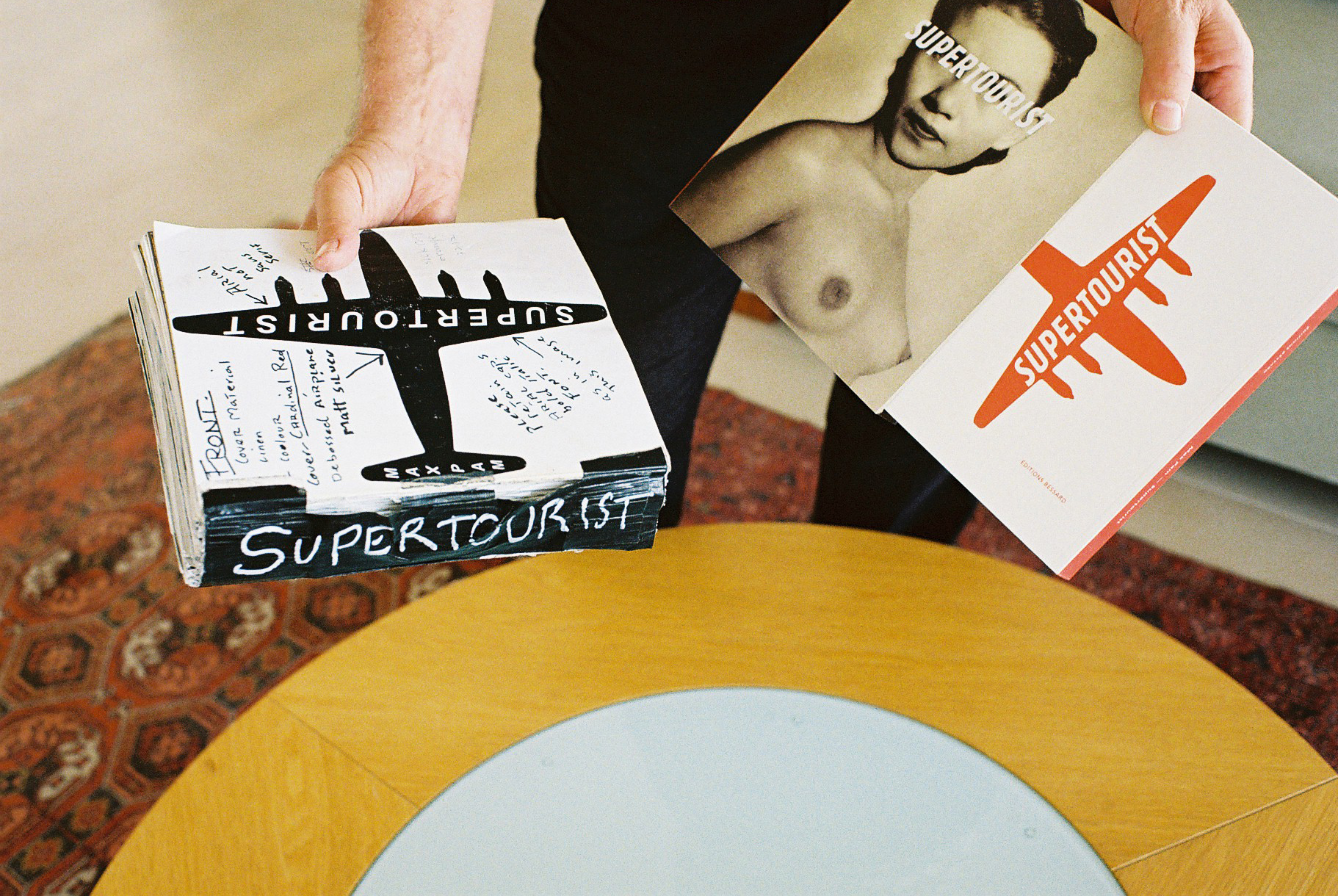

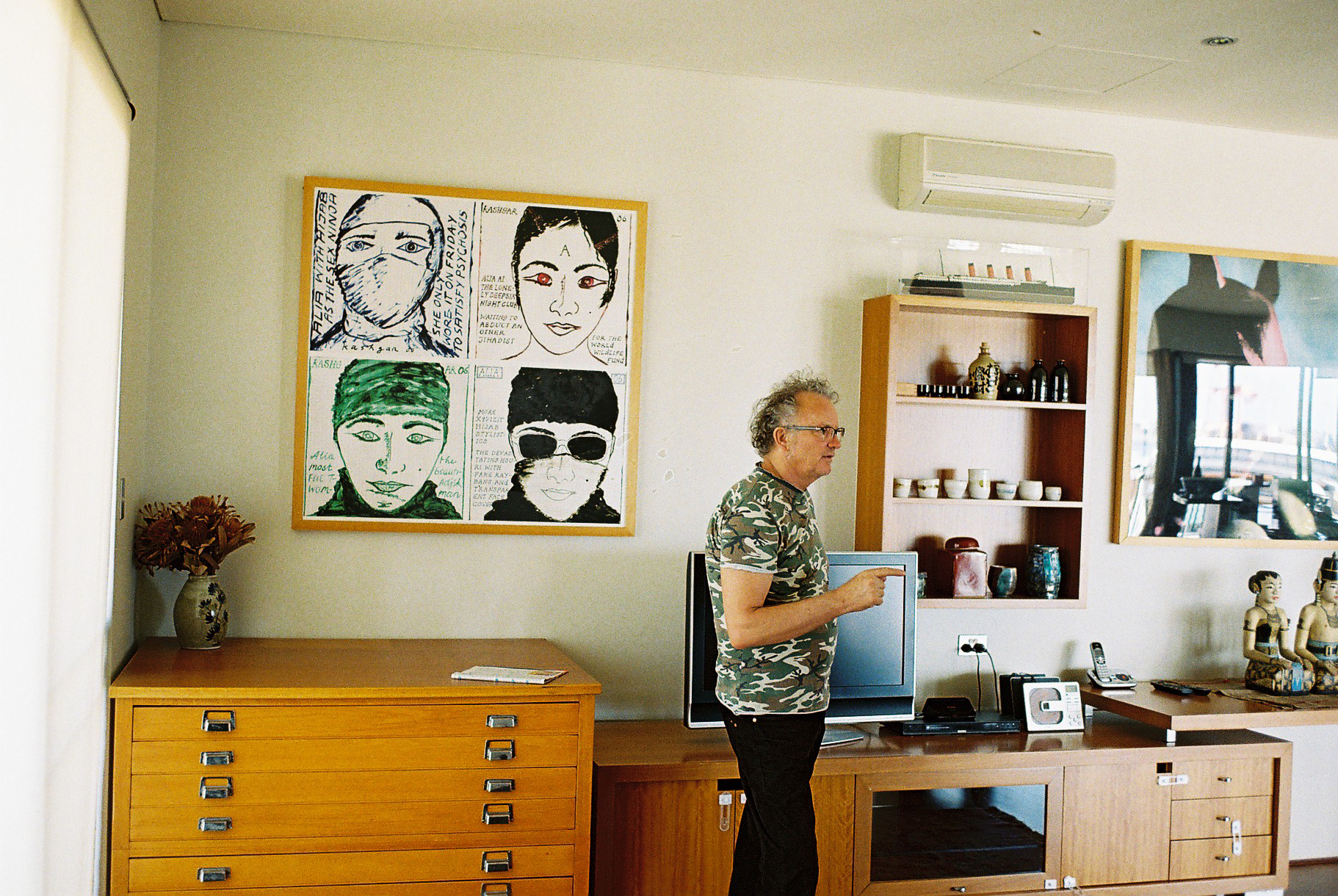

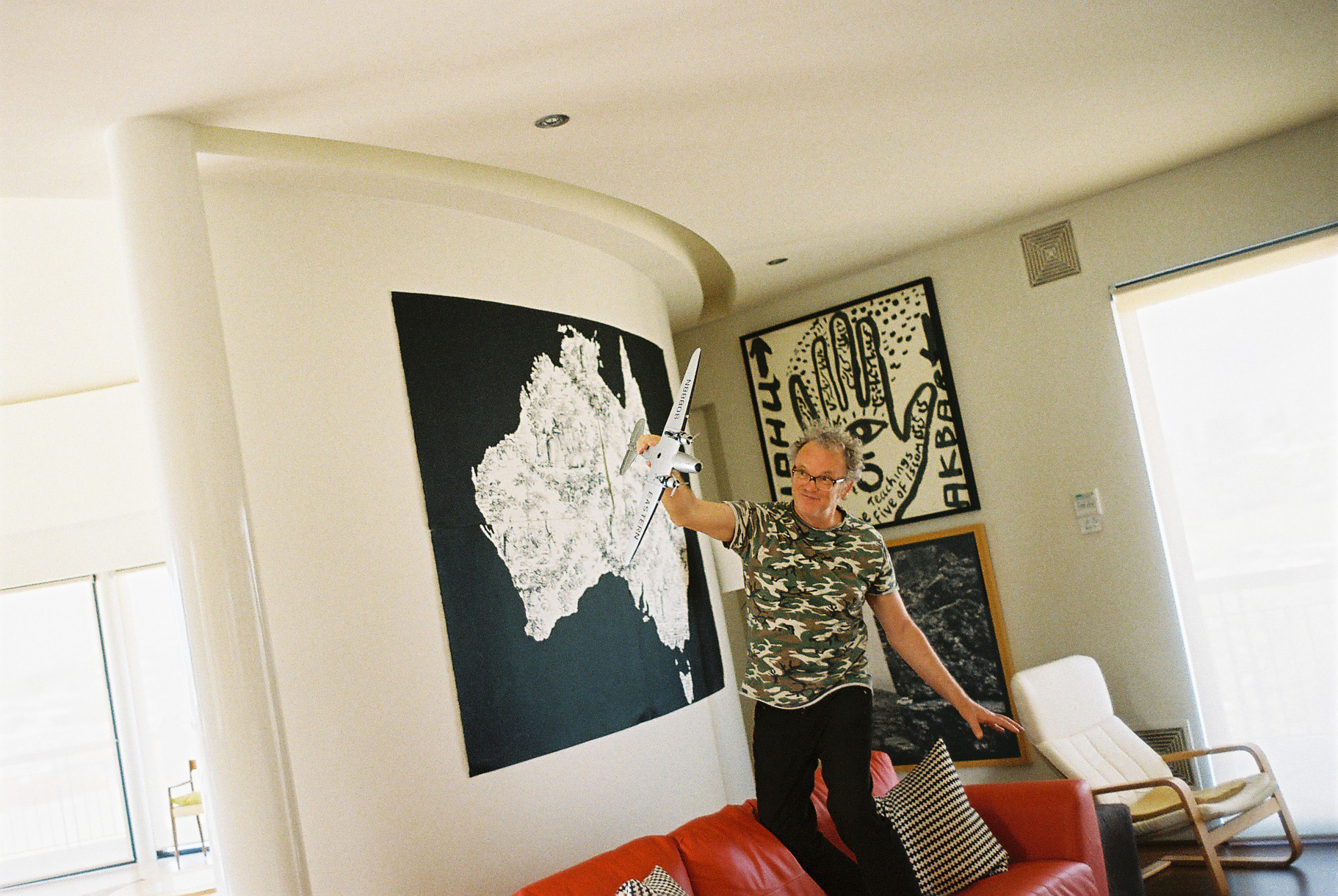

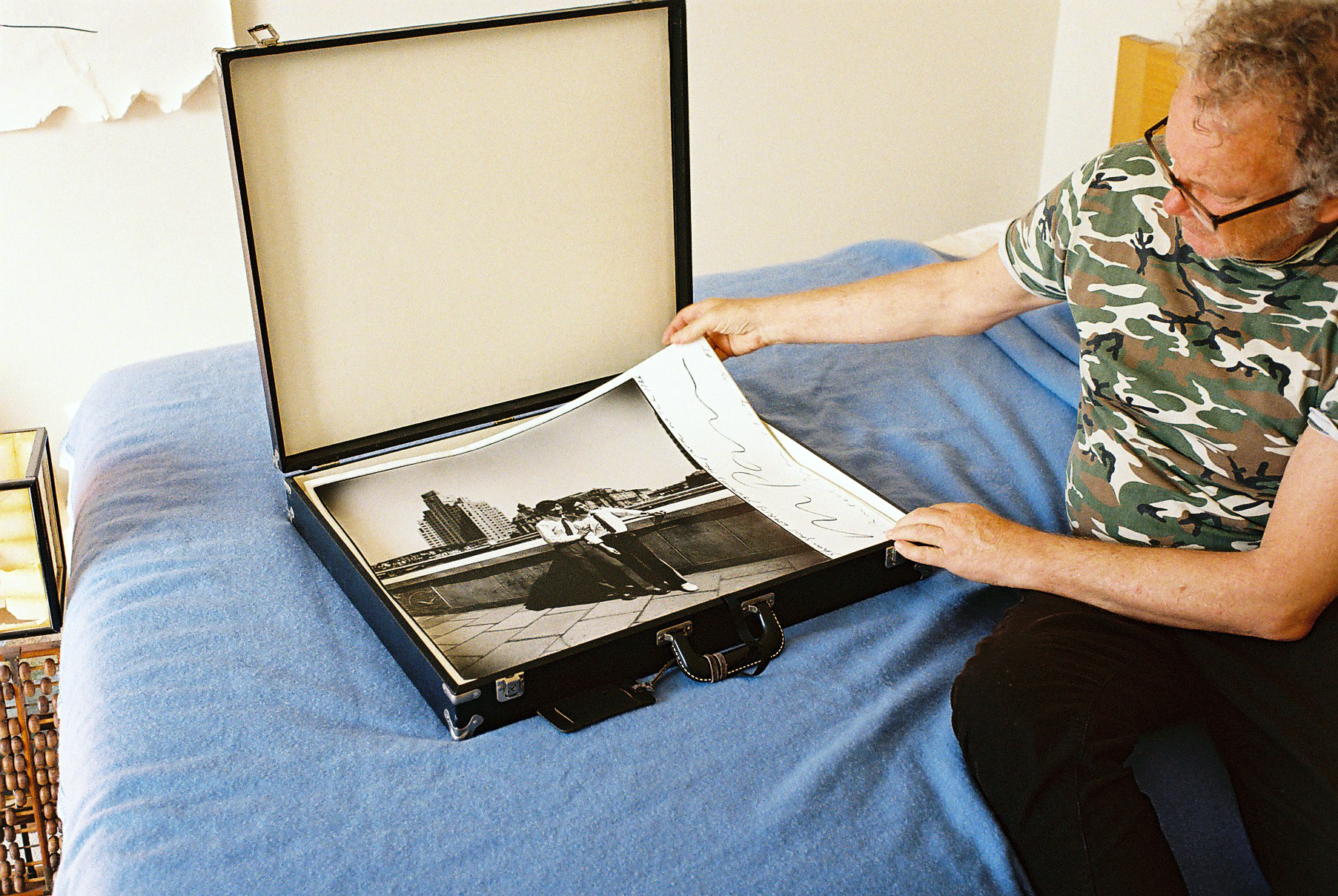

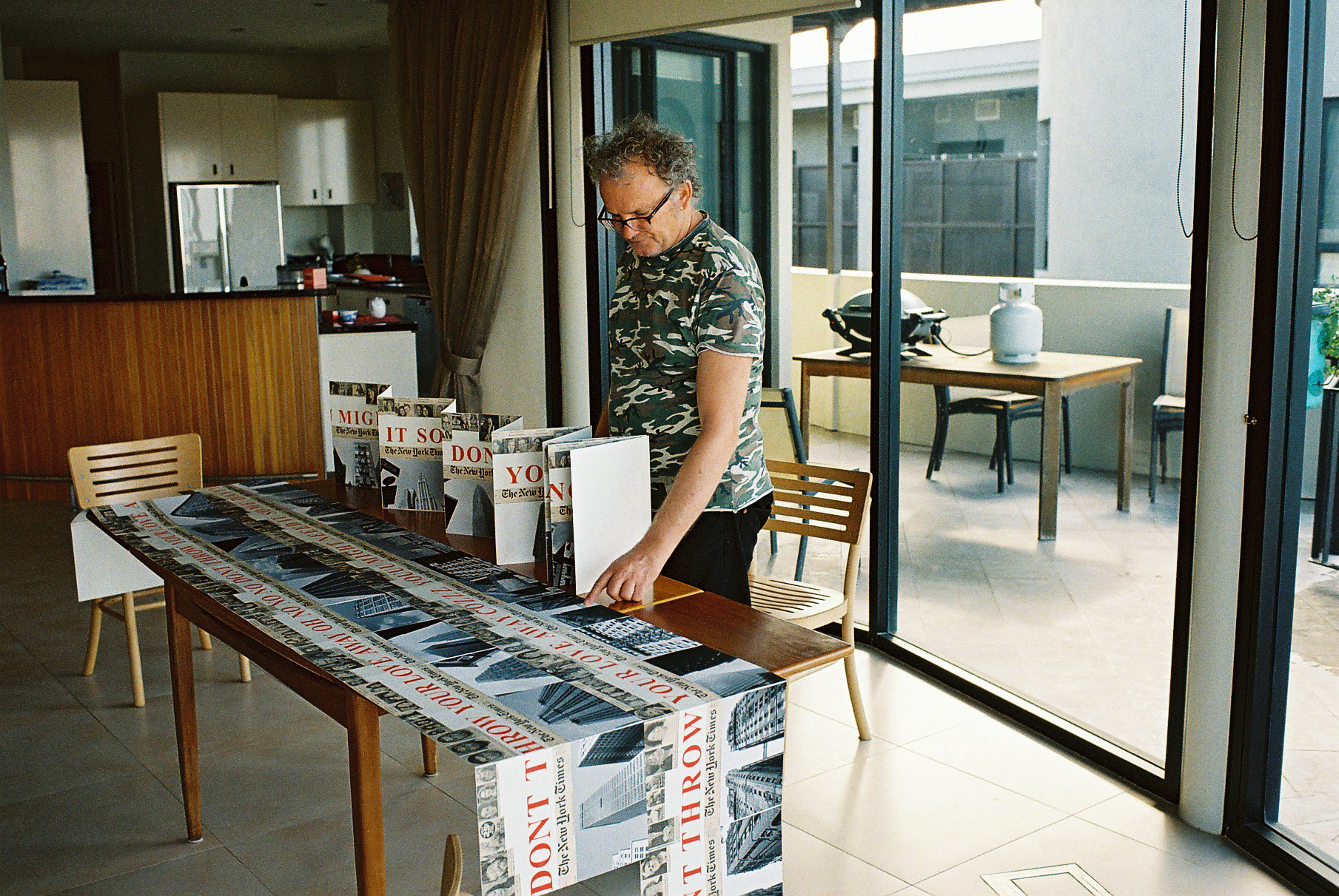

While keeping busy with photo commissions and attending his overseas exhibition openings, we tracked Max down for an afternoon at his uniquely positioned penthouse apartment with spectacular views. In the company of endless bookshelves stocked with just as much of his own work as other people’s we discussed what it means to be a contemporary photographer in the 21st century and his early years working as a photojournalist. Max’s most recent publication Supertourist is an epic artists’ monograph that was over ten years in the making. Wrapping up his last year as a university lecturer in photomedia before retirement, today he is as energetic as ever and the end of his artistic career is nowhere in sight.

Max, you’re originally from Melbourne right? What first brought you to Perth and what has kept you here?

I left Melbourne in 1973 for good. I spent quite some time away from Melbourne between 1970 and 1973, but in 1973 I left for good. I wasn’t happy with Melbourne at all and even going back there now I’m not happy with the place. Just my personal experience I suppose. My sister had her first child and she lived in Perth, so I figured that I’d get the boat from Fremantle – the port of Perth – to Singapore. You could get dormitory class on the boat back then. It was ten days on the Indian ocean for 75 dollars. It was a beautiful way to travel. So I caught the train across from Melbourne to Perth. My sister was living in Peppy Grove.

I stayed with her for about three months. I got a job working in a photo lab out in Belmont. It was kind of mass production photography with portrait snapshots, I worked in the photo lab and operated the film machine. That gave me three months experiencing Perth. I was really on my way out of Australia and wasn’t in a hurry to ever come back. That was my mindset when I got to Perth, however after three months in I figured that I really liked the place. I really connected with it in a meaningful way. So I after my trip to India I was able to contemplate coming back to Australia, which certainly wasn’t my thinking before I crossed the Nullarbor – the desert between Melbourne and Perth. Good old Perth, you got to love Perth.

Did you live in Borneo for a while during that time? Were you doing some work as a journalist there?

Yeah, I couldn’t work. I was in Brunei while my wife was working for the sultan of Brunei’s medical service. Basically the condition of the deal was that I could stay there with her, but I couldn’t work. Which suited me fine. I didn’t want to work. Jan, my wife, was earning enough for both of us. So, I started to do color editorial work for inflight magazines like Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines. I would think of somewhere to visit in that region, for example The Philippines or Thailand, and I’d do a story for the magazine which would usually cover the trip. I would shoot it with 35mm kodachrome 64 film and I would shoot my black and white stuff for myself with my big camera. I would create the magazine story with the picture editor of those magazines in mind.

I had really nothing but contempt for color editorial photos. What it did however, was make me much more productive in the field. It meant that I changed from shooting one roll of film per day – which was twelve shots – that were all carefully considered and slow in the way it evolved to working much faster. I think by the time the early 80s came along I didn’t have that kind of time anymore. I had a small family and doing the color photo stories made me much more efficient in the field. What would take me three to six months previously would only take me a month after that stint in Brunei. It was a pretty good education.

How much work did you do as a journalist? You talk about it like you seemed to enjoy it?

A lot of my work is informed by photojournalism. I don’t know what percentage, it could even be divided by 50 percent between the visual language of photojournalism and photography as a contemporary art form. For me doing photojournalism was and is something I can do. When we lived in London in the early 90s I worked for a French photo agency and I was the representative for the French journal Liberation in England. I did lots of stories for them and looked at stuff I normally wouldn’t go near out of my own volition, but because they were paying me and commissioning me I did it. And I got some really good enduring photos out of that. So, I’m pretty confident that if somebody said to me, “you can’t make any money out of anything other than just working on hardcore photojournalism,” I know I’d have that down. I know I could do a good job. It’s just that I only really wanted to photograph what I wanted to photograph. I think there is a pay-off for being stubborn about what you want to do about what you want to achieve.

You famously turned down an invite to the Magnum photo collective. What was your reason?

The Magnum thing. It was a real honor to be tapped on the shoulder in 92 in Paris. The president of Magnum – François Ebel at the time – came to an exhibition opening of mine. I knew François from quite a few years before. So I went to meet Magnum at the London office. It was in Brixton not far from where we lived. I really didn’t like the people I met there, I had no connection with them at all. So it wasn’t about not joining Magnum, I would’ve joined Magnum if the people in the London office had been even half human. I would have loved to have joined Magnum but the people I met once I got in the office made me think it really wasn’t worth the effort. At the same time I was invited to join this new photo agency in Paris. I went with them instead. That agency went down the toilet a few years ago. When they asked me to join it was kind of like the new kid on the block so it was exciting. I don’t regret walking away from Magnum however, that’s for sure.

You’ve just released your new book, Supertourist, your biggest work yet. You’ve been making photo books for 20 to 30 years or something now?

I’ve been doing journals since I was 20. I started my first journal on my first trip away from Australia driving a VW from Calcutta to London. I carried on from there. I was at art school in London. So it has always been part of my process from the get go. I mean it has always been a review tool for me and a repository for writing about my process, ever since 1970 – that’s quite a few decades of practice now! I’m slow to evolve with my photography so that process of keeping the books, nudging them this way and that, it helps.

The last three books you produced seem to be some of your strongest works: Ramadan in Yemen, Narcolepsey and Supertourist. It seems you’ve got more and more energy to make books as time goes by. Do you feel like you’re slowing down at all? Is your creative energy still flowing?

Yeah it is. Going to Italy recently was interesting. In Italy I was working on this thing called the Adriatic coast project. Basically I had four days to do it. It was pretty underwhelming but I was on fire. I got about 50 good pictures in four days. As you age you can still really evolve as a photographer. I think that’s really indicative of still being able to do it, still having the juice to do it, and doing it better than I ever could of before. It’s sort of interesting how, if you do have a long slow career like mine has been, it just keeps going if you have the opportunity.

I remember in the early 90s on the strength of my book GOING EAST that won the photobook prize at d’Arles I got offered quite a few projects. I remember one in particular in Andalucia, in Spain. Centered around Almeria I had a week to comment on Almeria with my camera. I had a week of rubbish really. I didn’t respond to Almeria at all. There was nothing there I really wanted to photograph but I was being well paid to do it so of course it was important to go through the process but I was really disappointed with what I got. What amazed me was that this project was so well funded. They had the list of everyone who was hot in photomedia working on the project, they had people like William Klein, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Martin Parr, among others. This was when Martin Parr was really at the height of his power and he did his best work. For his week in Almeria he did some extremely good work. It was a lesson for me. I looked at my stuff and I looked at his stuff and I learned a lot from that. I think part of my learning process is always learning from my mistakes.

Basically, I was unprepared for the project because I wouldn’t choose to go to Almeria and photograph normally, and my whole modus operandi was going somewhere where I wanted to be and commenting on it. The brief was the opposite to how I worked. But the wild thing is, here I am 20 years later doing the same thing really.

I want to talk about the cliché, how do you feel the digital age has transformed photography? I am interested to hear your perspective on it. With the internet, a million blogs, every man and his dog having a camera and wanting to be a photographer, do you think it is for the better?

For five seconds photography was very cool. Simply because it was the art form of choice for gen X and gen Y. You could say something about the specific culture you connect with and you could say something about your personal life. Maybe you’re not a good writer or you’re not good at anything else but you do have this ability to interrogate aspects of your life that you see as important and turn those things into a visual language. A lot of people got onto that with digital cameras in particular. It took the expense out of the process among other things and it gave the young questing photographer the tools to interrogate their worlds in a way that was very free and easy. But on the back of that came an almost oversubscription to photographing anything and everything that moved. There are too many photos out there.

People have been overwhelmed by photos and the idea of posting them every five seconds: this is me picking my nose, here I am massaging my scalp. The banal has kind of hijacked moments that people used to photograph because they were really aware of them. They were aware of them in a way that connected with their camera. It got lost in translation. Now it’s a question of tell me something I don’t already know or haven’t already seen. I think people are now suffering from a lot of photomedia fatigue. It’s not cool anymore, it’s just something everyone does. I actually think it’s quite an exciting time to be a photographer because there’s so much wallpaper out there. The really committed people operating a camera are going to do something strong. I think there’s always opportunities.

You have some strong artist influences in some of your work. I know August Sander’s work being one with the double portraits – an obvious one there. Is there much talent out there in the 21st century?

There’s good work out there. I like Tina Barney’s work a lot, she’s an American photographer and I like how she operates. Actually she’s not that new on the scene. Photomedia has a bit of a short attention span with regard to who’s hot and who’s not. A lot of really classy performers get lost in the woodwork. I still look for inspiration from the modernists. Not a lot that’s happened in the 21st century so far has really been meaningful for me. I still look back to the 20th century for inspiration.

There are a lot of photographs nowadays that appear to have all been taken before, which is not necessarily a bad thing. However, I’m just really amazed when I see something completely new. I guess there’s not too much room for originality.

Well, for me the last big thing to happen in photomedia was Nan Goldin, with her Ballad of Sexual Dependency in 1984. So that’s a long time ago. Some people would argue that there have been substantive players since then, but not on such a massive scale. Nan Goldin changed the way people constructed visual language. She set them all up for the 21st century.

A lot of people talk about the difference between an artist practicing photography and a photographer. What do you think about this? Would you call yourself an artist or a photographer?

I don’t know about labels. We are all photographers. I think that’s the point, we are all potentially writers as well. We are all potentially everything. I mean I taught myself how to use watercolors and I taught myself how to draw. There are lots of things we can do, but somehow these labels, I am this or I am that… I mean sure a brain surgeon, I understand how that label fits. When it comes to the notion of modernists and art and where it comes from and where you can take it, anyone can have a stab at that, and you can call yourself what you want. No one has the right to say you are not what you are.

Max thank you for the visit and chat. To find out more about Max’s photography visit his website here. His latest book Supertourist is available for purchase through Editions Bessard.

Photography: James Whineray

Interview & Text: James Whineray