At a time when most architects dream of building colossal structures, Antonin Ziegler embraces the human scale of the private home.

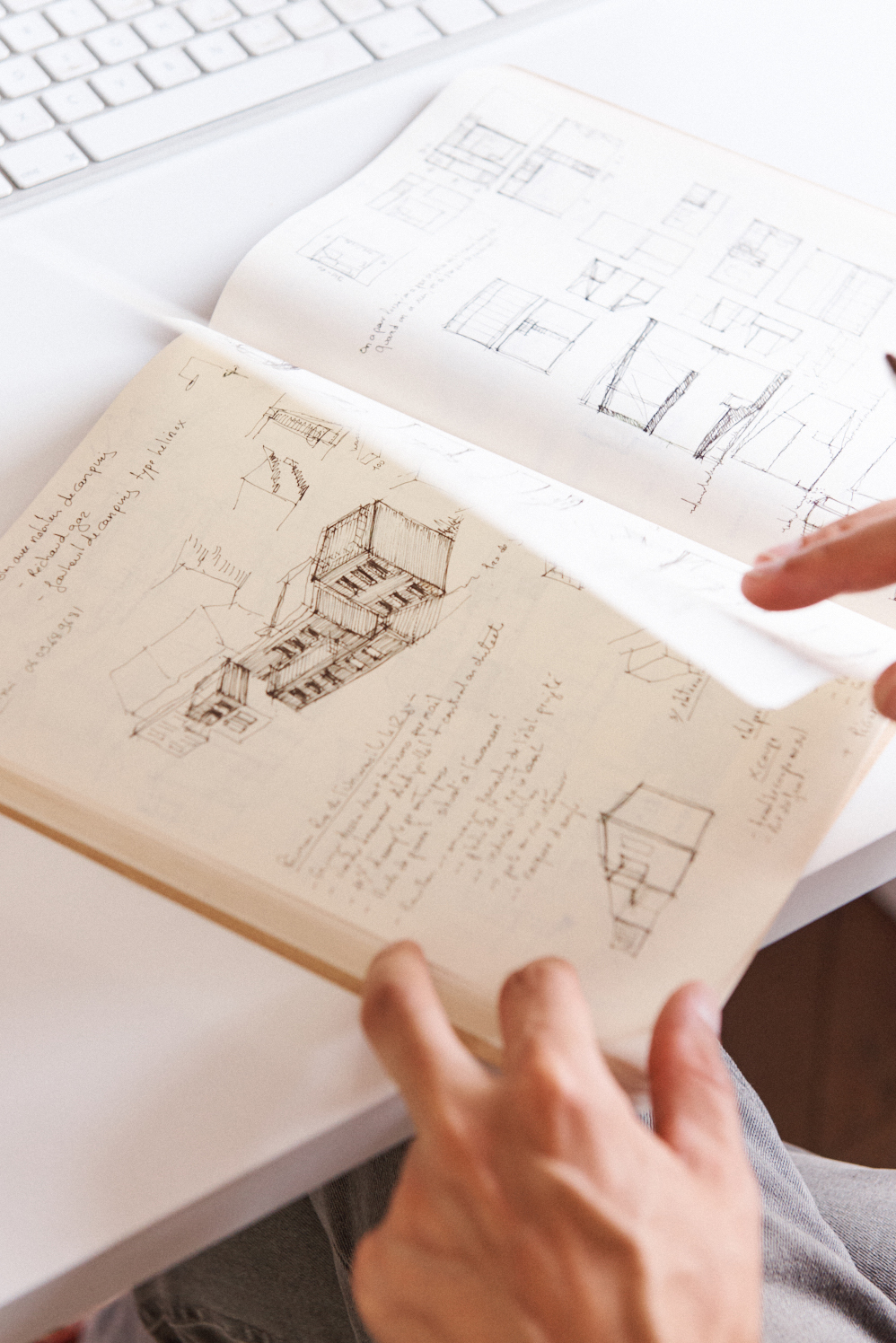

Ziegler’s interest in the essentials of architecture was evident early on. An eager student, he wrote his dissertation on the most basic of all building measures, the wall. “As an architect, the first thing you sketch is a line delimiting space on which a wall is built,” he explains. “Once you have a wall you can create shelter and shelter, as the most rudimentary function of architecture, has always been very interesting to me.” Ziegler’s own residence, which he conceived for himself, his partner, and his design studio, was built upwards on a petite plot of land on Rue Ménil 107, a quiet street in a northwest suburb of Paris. Standing narrow and tall behind a metal gate, Le 107, as it has come to be known, is a sculptural portrait of the independent architect.

This story is part of Architect Dialogues, an interview series by Freunde von Freunden and Siemens Home Appliances that explores current design philosophies, urban living trends, and global challenges with four award-winning architects and interior designers.

“What makes Le 107 work is a mix of verticality and openness. It only has a 28 square-meter footprint, but it feels a lot bigger than it is.”

“As a teenager, I loved to venture across the city at night, watching the urban landscape unfold,” he says. The lasting impression sparked a trajectory. After studies at the architecture school of Paris La Défense (now Paris Val de Seine), Ziegler graduated with a diploma from Normandy’s ENSA (The National School of Architecture, Normandy) in 2003 and began his career at large Parisian firms such as Paul Chemetov. Soon after he joined the Normandy agency CBA Architecture, where, at only 27 years old, he was supervising entire building sites. Award-winning designs for apartment buildings and office spaces under his belt, a sense of adventure struck and Ziegler departed for Canada in 2007. Working for YH2 in Montreal, the streak continued: Geometry in Black, a modernist multi-unit forest dwelling his team designed in the French Canadian Laurentian Mountains, was awarded the 2011 prize of excellence by Quebec’s Order of Architects. “I enjoyed the creative freedom that came with residential projects such as this, as I was the only point of contact for the client,” explains the architect, who admits that he prefers to work alone. Following a phone call from CBA Architecture offering that he open the Paris branch of their office, he returned to France.

In 2012, he founded his own design agency to regain a sense of freedom and fully dedicate himself to private homes. Since then, self-sufficiency has become a leitmotif. “When I take on a project now, I only design what I am capable of getting done myself.” That’s also how he conceived of Le 107. “Visited on Monday, bought the following day,” Ziegler recalls, falling in love with the site’s original structure at first glance. Between 2015 and 2017, he transformed what was a crumbling early 20th century dwelling into a luminous multi-story home. “I remember thinking oh, how fun, this house is a complete disaster, everything will need to be redone.” The plot’s narrow dimensions—4.5 by 25 meters—didn’t make things any easier. But Ziegler likes a good challenge. “Constraints fuel my creativity,” he says. “It is within limits that we can express ourselves.” Ziegler embraced the plot’s unforgiving narrow limitations, but did so vertically. Three-stories-high, Le 107 juts out prominently from behind the front gate. And yet, it blends into the tile-roof tapestry of Asnières-sur-Seine, the working-class neighborhood Ziegler now calls home. Whether he builds homes in an urban area or the countryside, espousing the surroundings architecturally is one of Ziegler’s principles. Le 107’s composite facade, for example, is made of planks of pinewood, concrete, cement primer, and sheet metal, referencing material surfaces common in the area. “I chose modest materials that blend in with the neighborhood. They had to be economical, too, so I could afford the large bay windows, which were a significant chunk of the building’s budget,” Ziegler explains. “I generally dislike materials that imitate or hide. Whenever possible I use the same materials for a building’s exterior and its interior.”

“Constraints fuel my creativity. It is within limits that we can express ourselves.”

It is no surprise that Le 107’s facade is profoundly visual, if not photogenic. “I watch a lot of films and I would have liked to be an artist,” Ziegler says. “I also practice photography, a craft that intimately relates to architecture—so much so that I wonder whether I might have become an architect in order to create spaces for me to photograph.” He frames every angle, every view within a building project like a shot and the 3D software he uses “captures” light just like a camera would. “In many ways, my work is that of a scenographer.” Ziegler also offers photography and visualisation services for architectural clients through his studio 213613R. Here, he draws inspiration from the melancholy of the mundane: parking lots, street corners, gas stations, hotel rooms, suburban homes. “I love the visual aesthetic surrounding Portland’s industrial zones, for example,” says Ziegler. “Perhaps that’s why I enjoy working with modest materials and why I have no desire designing luxurious villas.”

“I also practice photography, a craft that intimately relates to architecture—so much so that I wonder whether I might have become an architect in order to create spaces to photograph.”

American influences permeate the French architect’s practice. More than once, Ziegler borrowed ideas from icons such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and more recently Wendell Burnette. In fact, the biggest compliment Ziegler has received about his home is that “when sitting in the cabin nestled in the garden, you’d think you’re in Montana.” The cabin is a little room inside a glass cube Ziegler placed at the far end of his backyard. From here one has a leisurely view out at the main house. “It’s very Nordic and Anglo-Saxon to have an exterior viewpoint onto one’s own house, it’s seldom seen in France.” Japan is another source of inspiration: it can be felt in Ziegler’s obsessive attention to detail, the maximization of limited space, and the occasional clever twist: from the cube one can catch glimpses into the foyer of the house, which contains the kitchen—Ziegler’s favorite room. “I enjoy designing kitchens behind large windows, since that’s where life is lived, where people spend their time—they’re as interesting to observe as they are to live in,” he says. “It doesn’t matter whether it’s small or spacious, or if it only has two pieces of furniture, what’s important is that the kitchen is at the heart of the home.” Sure enough, Ziegler’s own kitchen is visible from every angle in the house. It functions as the building’s foundational base from which you ascend into the upper floors, all of which are bright, open spaces with no doors. “I hate rooms that are all closed up, they feel dead,” he says emphatically. “I try to design rooms that have no destination, that aren’t affected by layout dimensions, or their place within the architecture.” It’s the idea of interchangeability that Ziegler is drawn to and it’s evident in his own house. “I wanted Le 107 to feel somewhat dreamlike, to live by its own rules,” he says. There’s a surprising air of generosity and spaciousness to how the three floors cascade into one another; a winding path that has sometimes led guests to lose their way. “What makes Le 107 work is a mix of verticality and openness. It only has a 28 square-meter footprint, but it feels a lot bigger than it is.”

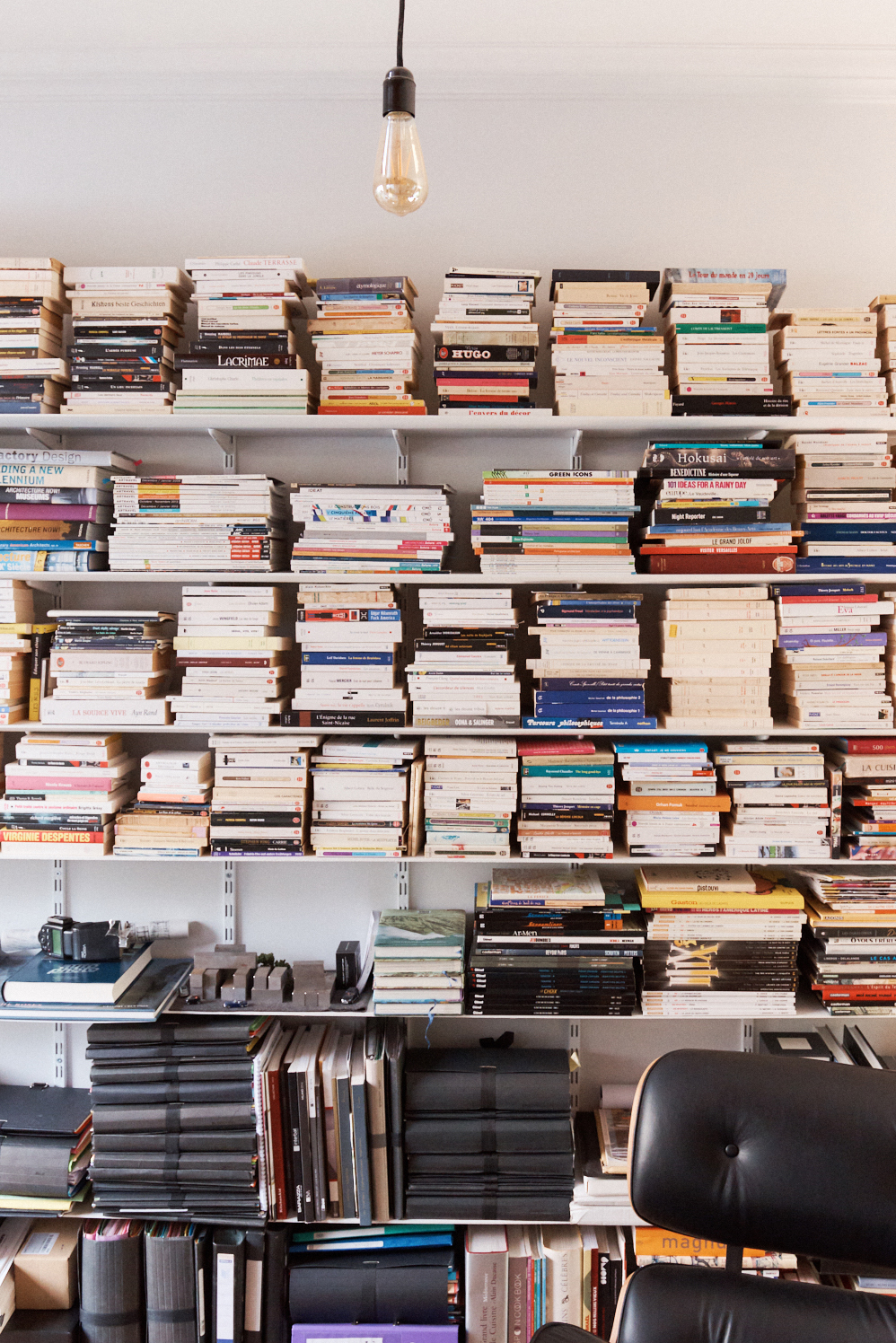

Ziegler’s office sits firmly in the middle of it all. It’s a bright space on a first floor mezzanine and entirely devoted to his work. “I never do any work elsewhere in the house,” he insists. “In fact, after a long day of drawing and drafting, I happily abandon the studio to pursue other interests.” Cycling and wild camping getaways are among Ziegler’s favored activities. “I relish opportunities where I can escape the city and surround myself with nature. Le 107 is everything I wish in a home, but even as a fervent urbanist I need to get away from it every once in a while.”

A collaboration between Freunde von Freunden and Siemens Home Appliances, Architect Dialogues is a mini series that explores current design philosophies, urban living trends, and global challenges with four award-winning architects and interior designers. For more insights from Antonin Ziegler, the Paris-based architect profiled in this part of the series, see the extended conversation over at Siemens Home Appliances or go to Ziegler’s studio website. Stay tuned for upcoming entries to the series and be sure to check out our other portraits in collaboration with Siemens Home here.Architect Dialogues is supported by FRAME and Baumeister, who help bring select interviews from the series to new audiences on their end.

Text: Marie Godfrain

Photography: Thomas Chéné