Involved but without pity. Revealing but not intrusive. Photography must be candid. It must follow an approach. And yet, the most important thing is also for photography to stop acting as if it were invisible.

Jörg Brüggemann has been photographing the German autobahn for around a year and a half. Up until now, the resulting images have not been seen. For the Ostkreuz photographer, it’s gradually becoming clear which stories his autobahn photos can tell, and which story he wants to allow them to tell. That makes it seem as if the instantness—meaning immediate possibilities for dissemination—of today’s photography is leaving him cold in a comforting sort of way. But also in a way that suggests there’s a secret to the German autobahn that’s beckoning to be revealed.

During a conversation with the colleagues at the Ostkreuz agency, a feeling of skepticism arises. “What are you trying to get from the autobahn? That’s a total ’90’s topic.” Yet Jörg draws his motivation precisely from that: Photographing something that everyone thinks they already understand. For his earlier works, such as his portrait series of the global metal and backpacker scenes, this impulse often led him far away from Germany—but now he’s dedicated himself to what’s going on just outside his front door. “At some point, I realized that there’s no need to travel far and wide to get this kind of input, and that we tend to stay in our bubbles even when we travel—which is often quite the contradiction.”

This portrait includes exclusive photographs from Jörg’s current project on the German autobahn paired with shots taken simultaneously by our in-house photographer Daniel Müller.

“German politicians are terrified of being photographed.”

Brexit and last year’s election in the United States are the most recent indicators that our bubbles and media filters have become hotly debated symptoms of our time. An era in which nearly no one knows what their neighbor is thinking, while others fill comment sections with hateful remarks using their real names. A state of things that Jörg is not inclined to turn a blind eye to. “Something I would never do is block people on Facebook. I see over and over again someone threatening to delete all of his annoying contacts. But I actually think that you have to absorb it.” Taking it all on and not turning away from it, he sees as part of his role as a photographer. Because good photography seldom happens without taking a clear stance. “Viewing the world on a theoretical and intellectual level, and then photographically on a physical level, and then finding that perspective on location that aligns with the one in your head—that’s the goal. If you manage to consolidate the two, a good image with a good story is the result.”

While Jörg’s personal works are more long-term projects which allow him to sort out the relationship of the image in the mind and photography step by step, contract work is much more about meeting expectations. When he photographed Frank-Walter Steinmeier—Foreign Minister of Germany at the time and now Federal President—for the magazine Cicero, Jörg found himself confronted with a whole new situation; “For the first time in my life, I had three minutes to photograph someone.” What he later delivered was the image of a politician who didn’t quite know what was happening to him. “I placed him in front of a white wall and used the flash. He probably couldn’t imagine what the image that I was taking of him looked like.” Jörg knows from his Ostkreuz colleague Maurice Weiss, who has been photographing politicians for a long time now, that “German politicians are terrified of being photographed.” The reason for that is possibly because very a few of them realize how images communicate, “and above all images of themselves. They see themselves on the image and lack the distance to view it as an image in and of itself.”

Jörg’s Studio

“The media is just as much a part of the story and that has to be exposed.”

It always takes two to create an image, even if the professional ethos of many photojournalists would likely refute the notion. Jörg’s weakness for intense flash is in part about how he wants to, or even has to, integrate his role as a photographer into the image to avoid becoming an adherent to an allegedly objective image philosophy. In that way, the back of Frank-Walter Steinmeier’s sweaty and washed out neck betrays just as much about the photographer as it does the subject. We’re reminded that what we see is a highly subjective view. The subject of the portrait is not revealed so much as the photographic construction itself, which for a long time denied its entanglement with the depicted situation. “The fear of being portrayed incorrectly and of the resulting public image is indeed very understandable,” Jörg admits. “Seeing beyond certain codes of conduct and getting a close-up view may correspond to a more realistic image in the moment. Maybe that would make politicians seem more human again.”

When the Ostkreuz member meets other photographers and photojournalists during his contract work, his approach is occasionally met with a lack of understanding. “There are still photographers who believe that they can’t disturb the situation or interact with people because it would falsify the situation—but that’s exactly what they’re doing simply by being there.” Jörg’s amazement about this naïvety reached its climax last summer on the Greek island of Kos. There, while other press photographers lined the beach waiting for the next boat of refugees to arrive on the shoreline, Jörg dropped back and instead photographed them. “I knew I could only take one photo. And that meant taking a step back to get the photographers waiting on the beach in frame. Because I believe the media is just as much a part of the story—and that has to be exposed.”

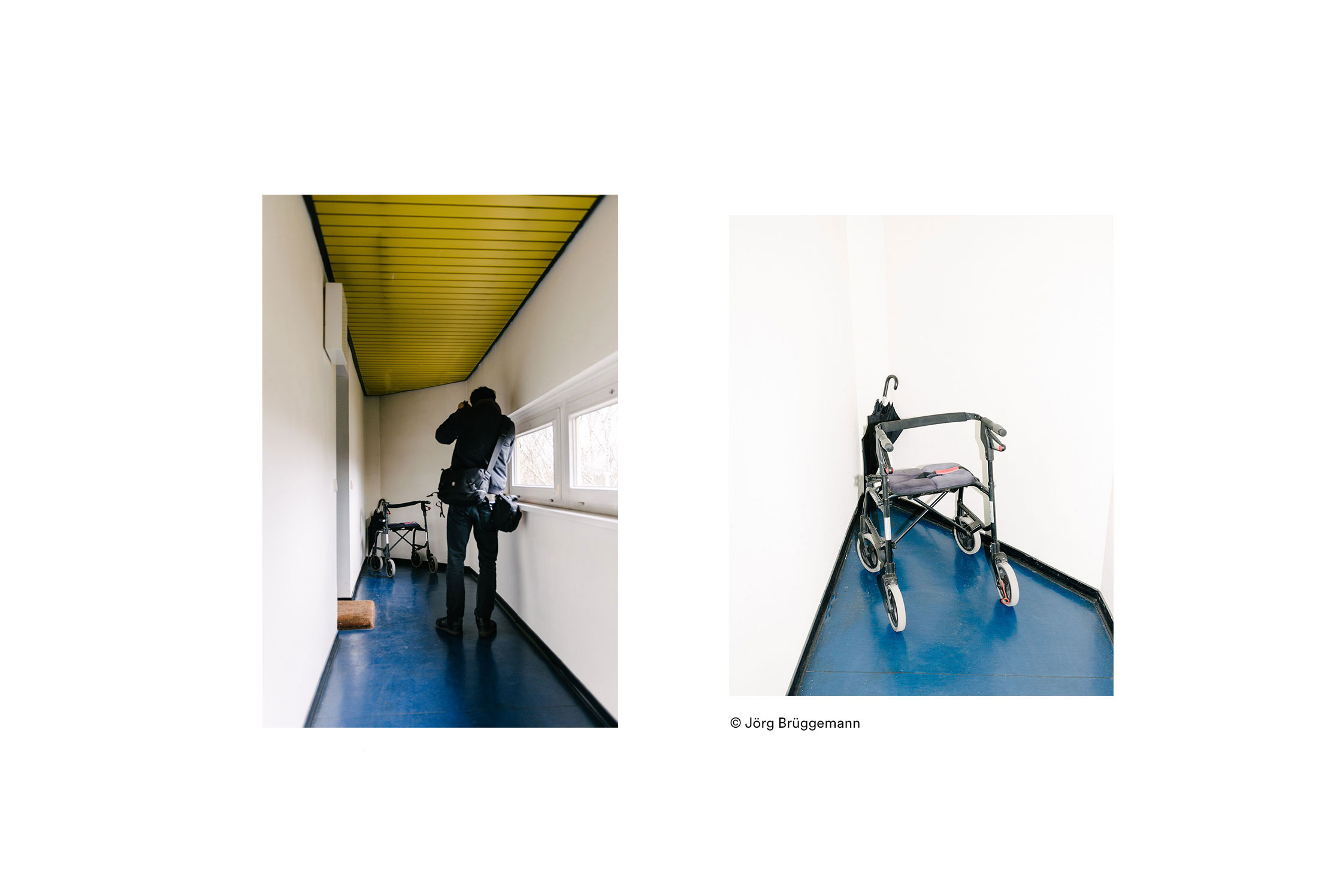

Built across the autobahn

The housing complex at Schlangenbader Straße

“I’m really not interested in growing old and looking back at a portfolio of work in which everything suddenly makes sense.”

The ways and means that help Jörg to highlight the subjectivity of his images—that give them a defining characteristic or an ironic touch—are always different. The challenge is not to fall into a pattern, Jörg explains: “So-called style is actually a trap that you can quickly find yourself in and in which every photograph admittedly falls into in one way or another. But there are a few that manage to find a new and probably correct photographic execution every time, and I find that much more interesting than having one good idea that repeats for a lifetime.” Jörg also finds the idea of a continuous overarching theme throughout his work strange. “I’m really not interested in growing old and looking back at a portfolio of work in which everything suddenly makes sense. Maybe there already is a continuing theme in my work that I just don’t see. But what I really want is to be able to pursue what attracts me in the moment.”

This understanding of photography that must always question itself is something that could grow with the backing of the Ostkreuz agency. The exchange with the other members on their own work, but also on the communal negotiation of what Ostkreuz is actually capable of being, is of particular importance for Jörg: “That’s an absolute luxury in a job that often inevitably results in a ‘lone wolf’ existence.” And yet the learning process in institutions of higher education is usually conducted through constant exchange. “After graduation, you find yourself suddenly fending for yourself and some try or even attempt to force the restoration of a shared context – and I can certainly understand that.”

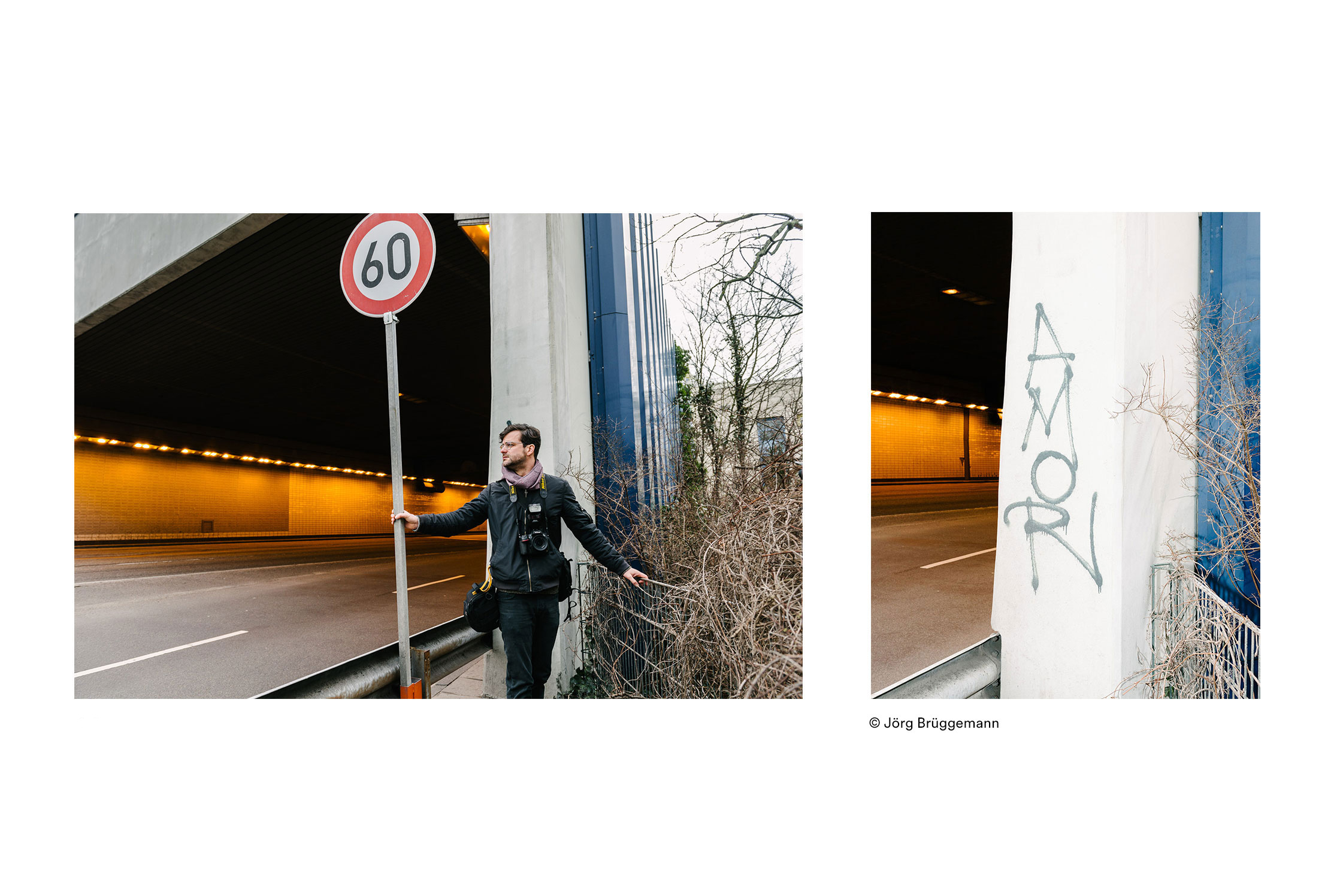

A10 near Michendorf

“Sometimes it’s easier to take on the role of the outsider and examine the special qualities or exotic nature of a place.”

Ostkreuz was founded in 1990 based on the model of the Paris Magnum agency—meaning that it was founded by the photographers themselves. The current members are also the owners of the agency, which creates a strong connection and high degree of closeness among the group. Since joining them some eight years ago, Jörg has come refer to Ostkreuz as his second family—a privilege of which he is completely conscious. Despite the variation in their images, the photographers are united in the attempt to provide a candid and human view of the world. A different description of the common principle provides the concept for author photography: a concept which interprets the photographer as a writer who chooses topics and implementation himself. For Jörg, it’s all about “sympathetic closeness and critical distance” when addressing things thematically, and “a balance between confidence and self-doubt” for his self-perception in an inseparable connection to his own experiences.

When Jörg talks about his excursions up and down the autobahn, it seems as if there was something there that he even has to explain to himself. “The autobahn is actually a very democratic place. Pretty much everyone in this country uses it. At the same time, the autobahn is also an incredibly impersonal place. Everyone is separated into their own space; even at the rest stops, there’s hardly any interaction.” For him, it’s possibly a the question of what the country he’s examining means to him. The autobahn is of course a German cliché—the land of export champions and German car brands, Kraftwerk and no speed limit—a series of associations. But about the people living in this country, and how they feel, the autobahn seems to reveal so little. Maybe it’s worth taking a closer look.

For someone who has traveled a lot in recent years and who has photographed almost more in foreign countries than in his own, taking on a topic like the German autobahn is a change of viewpoint. “Sometimes it’s easier to take on the role of the outsider and examine the special qualities or exotic nature of a place,” Jörg explains as he reflects on his earlier work. “But there’s not a lot that’s special about the autobahn.” And that’s certainly part of the challenge that photographers face: finding a new perspective on the things that surround them every day.